Ch. 1: Theory Integration and Prevention

*Note that portions of this chapter were informed by content presented in Begun and Murray (in press), Begun (1993), and Begun (1999).

A wide range of biological, psychological, and social context theories and models concerning substance use, substance misuse, and substance use disorders can be integrated to inform intervention strategies and future research from a biopsychosocial perspective. A vulnerability, resilience, risk, and protective factors framework is presented here to help conceptualize and integrate multiple, diverse theories and evidence. This integrative framework reflects both a biopsychosocial and social work person-in-environment strengths perspective. Thus, it can inform interventions and policies that help change individuals, their environments, and the interface between individuals and their environments. The framework was derived from E. James Anthony’s early work concerning the etiology of schizophrenia.

The vulnerability, resilience, risk, and protective factors framework is applied at the group or population level for purposes of informing/planning intervention strategies and research based on logic models and existing evidence. The state of evidence and assessment tools, at this time, is not sufficiently well-honed to predict individual outcomes, so the framework is not used to assess or predict what will happen for an individual person or family. Here, the framework’s four steps are outlined.

Specify the problem. The more specific the problem definition, the easier the task of identifying and integrating varied theoretical models becomes (Begun, 1999). For example, “preventing adolescent initiation of alcohol misuse” is reasonably specific, whereas “preventing substance use disorders” is overly general. Specificity might include specifics of an addictive behavior (e.g., a specific substance, type of technology, or form of gambling) and/or a target population (e.g., a specified age or developmental phase, racial/ethnic group, self-defined gender identity, sexual orientation, co-occurring problems, or problem severity level). It is important, as well, to be specific as to the system level being addressed: individuals, family subsystems, family systems, neighborhoods/communities, institutions, or geographical regions. Specificity about the prevention target hones your aim.

2. Define the relevant vulnerability/resilience continuum. Once a prevention problem is clearly specified, evidence concerning known vulnerability and resilience factors can be located and critically analyzed. The vulnerability/resilience continuum refers to factors intrinsic to individuals (or other system level specified in the first step). In other words, factors that individuals bring with them to any new situation or experience, such as those we studied in Module 3 (biological models) and Module 4 (psychological models). These include the factors like: genetics, neurobiology, and other biological processes; temperament and personality characteristics; abilities and disabilities; co-occurring problems; past experiences and learning; and, current attitudes, beliefs, knowledge, and behavior patterns. Some factors reflect individuals’ vulnerability to the specified problem, other factors reflect aspects of their resilience. Together evidence concerning these intrinsic factors help determine where along a vulnerability/resilience continuum a group of individuals might be situated. For example, a recognized vulnerability/resilience factor with a great deal of supporting evidence and clear mechanisms by which it happens is the age at substance initiation—the earlier individuals begin using most types of substances, the greater the probability of developing a substance use disorder during their lifetime. Young age of initiation pushes the continuum toward vulnerability; delaying past emerging adulthood pushes the continuum toward resilience.

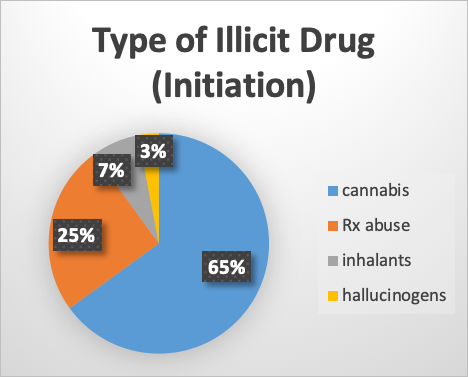

At this point, the task involves identifying the theory and evidence related to specific factors. For example, consider evidence related to the gateway drug theory. If the identified problem is to prevent opioid/heroin use among adolescents and emerging adults, multiple theories and pieces of evidence will need to be considered for integration. One of these concerns the conflicting evidence surrounding cannabis use as a “gateway” to use of other, “harder” substances. Early evidence suggested a correlation between initiating heroin use and prior cannabis use—a very large portion of individuals using heroin had this in their past history (a vulnerability factor). However, subsequent and more sophisticated research approaches have called this gateway conclusion into doubt. First, the vast majority of individuals who have used cannabis never progressed to heroin use. Second, the distinction between “mild” and “hard” drugs is arbitrary and subjective. As we have discovered throughout the course so far, any psychoactive substance can be considered potentially addictive—some may have a higher percent of use or faster progression to addiction than others, but placing them on a single, comparative “seriousness” continuum is not grounded in evidence. A third blow to the gateway drug theory is the tremendous diversity in substance use behavior observed across different geographical areas, ethnic and socio-economic groups, social networks, and cohorts over time. In the 2011 NSDUH survey, about 2/3 of participants who initiated illicit substance use during the study year reported marijuana as the first illicit substance used. However, this means that 1/3 started with something else: almost 25% started with prescription drug abuse instead, 7% started with inhalants, and just under 3% started with hallucinogens. This tremendous variability argues against a gateway drug theory—there are too many openings or access points involved for any one substance to be confidently identified as a gateway drug.

On the other hand, more recent events and evidence suggest that prescription abuse, particularly nonmedical use of opioid drugs, may represent a gateway to heroin use. Individuals entering treatment for an opioid use disorder (OUD) reported having “progressed” from prescription opioid use and nonmedical use of opioids (NAS, 2017). This sequence was also, by far, the most common pattern observed among surveyed individuals in the general population who reported heroin use each year in analysis of 2003-2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health data (NAS, 2017). Heroin, in many communities, is more easily accessed and less expensive since prescribing and dispensing restrictions have been introduced in response to the “opioid epidemic” facing many parts of the nation. “A number of studies have yielded evidence strongly supporting the conclusion that the recent prescription opioid epidemic has resulted in a significant increase in domestic heroin use and associated overdose death” (NAS, 2017, p. 207). The gateway theory concerning the relationship between prescription opioid and heroin misuse is bolstered by the fact that these substances have similar psychoactive and pharmacologic effects, including the capacity for cross-tolerance developing (NAS, 2017). Tolerance to a prescription opioid drug confers some degree of tolerance to heroin. Using higher doses of either/both increases the risk of overdose.

3. Risk/protective factors continuum. As with the vulnerability/resilience continuum, evidence concerning known risk and protective factors is identified and analyzed next. The risk/protective continuum refers to extrinsic factors. In other words, factors residing in current social and environmental contexts that we explored in Module 5 (social and physical environment contexts). The risk/protective factors continuum relates to “here and now” contexts and experiences; past interactions with the social context become a part of the vulnerability and resilience continuum—historical experiences of the environment become part of what is brought to new situations. For example, a history of adverse childhood events (ACES) becomes a vulnerability factor related to substance misuse; currently living in a traumatizing environment is a risk factor. Current risk/protective factors might include the presence (or absence) of alcohol, tobacco/vaping, or cannabis advertising in the neighborhood/community, ease of access to substances of concern, and social norms about substance use/misuse.

4. Integration. Consider now how the two continua intersect: bringing together the vulnerability/resilience continuum with the risk/protection continuum. This is conceptually diagrammed as a 2 x 2 grid specifying the general probability (low, moderate, high) for developing the specified problem under these complex circumstances (see Figure below).

|

|

|

Vulnerability/Resilience |

|

|

Risk/Protection |

|

low vulnerability/ high resilience |

high vulnerability/ low resilience |

|

low risk/ high protection |

I low probability

|

II moderate probability |

|

|

high risk/ low protection |

III moderate probability

|

IV high probability |

|

The result is an integration of theory and evidence to inform the development of intervention and policy strategies and logic models. For example, the low probability group (I) needs little attention beyond universal preventive efforts to maintain healthful status—maintaining both resilience and protective factors and minimizing new vulnerability and risk exposure. They are pretty much good to go (green light). On the other hand, the high probability group (IV) warrants a great deal of immediate attention with efforts designed to reduce both vulnerability and risk, as well as promote both resilience and protective factors. This group should stop us in our tracks, getting a great deal of our attention (red light). The two moderate probability groups (II and III) warrant attention in the form of selective or indicated prevention efforts to prevent their shifting into the high probability group (IV). They are the “caution” group (yellow light). Ideally, group II and group III populations also can be helped to more closely come to resemble the low probability population (group I).

This is where theoretical models and empirical evidence inform both specific interventions (including policy) and planning broader combined intervention strategies, whether the aim is prevention, treatment, or maintenance of gains achieved. A great deal of literature across many disciplines presents detailed and nuanced evidence related to vulnerability, risk, resilience, and protective factors surrounding different addictive behaviors. This framework provides a logical system for organizing the massive literature, only some of which appears in this handbook.