Ch. 1: Cannabis

Similar to alcohol, cannabis use has a rather long and storied history in the United States and some other parts of the world. Cannabis has been used in some cultures for hundreds, or even thousands, of years (Malcolm, 2020). Research and clinical practice related to cannabis has had to evolve over time, due to two significant forces. First, the concentration of psychoactive ingredients in cannabis plants has steadily increased over the past few decades (NIDA, 2019a). Potency prior to the 1990s was estimated to be less than 2%; the range in popular strains in 2017 was estimated at 17-28% and some concentrated oil products may even exceed 95% (Stuyt, 2018). Thus, individuals using cannabis products today face a higher relative dose compared to what past generations encountered. It is difficult to determine how much of the active ingredient a person has been exposed to—unlike the standard equivalents we can calculate with alcohol—because (1) different strains and growing conditions produce different concentrations, (2) different preparation methods affect concentrations (e.g., marijuana, hashish resin, hash oil, and parts of the plant used), (3) amounts used/inhaled in any administration vary, and (4) other products may be combined or contaminating the cannabis used (WHO, 2016).

Second are the dramatic shifts, revisions, and retrenchment in local and state policy across much of the United States concerning the use, possession, production, and distribution of both medical and recreational marijuana. Policy revision addressing mass incarceration and promoting smarter “decarceration” in response to the nation’s War on Drugs also have relevance regarding cannabis-related offenses (see Pettus-Davis & Epperson, 2015); federal changes in policy may be on the horizon, as well.

You will notice throughout this module the word “cannabis” is often used, rather than the heavily politicized word marijuana. Malcolm (2020), citing Antoine and Douglas (2018) explained that many researchers, scholars, and advocates express a preference for the more scientific term “cannabis,” citing racist and propagandist connotations of the word “marijuana”. He described the deep historical and social significance of cannabis use, noting that “it has been simultaneously reviled, denounced, prohibited, tolerated, and revered,” and that politicization of cannabis use has been heavily tinged with racism concerning African American, Caribbean, and Mexican populations. The word “marijuana,” originating in Mexico, has often been associated with stigmatized or marginalized groups, hence the stated preference for the less-politicized word “cannabis.” Common “street” names for cannabis (or marijuana) include pot, weed, grass, herb, nuggets, ganga/ganja, dope (though this can also mean heroin in some communities), reefer, ganja, hash (or hashish), Mary Jane, and stinkweed (https://luxury.rehabs.com/marijuana-rehab/street-names-and-nicknames/).

How Cannabis is Commonly Used

Cannabis refers to several psychoactive substances derived from either the cannabis sativa or the cannabis indicaplant (Malcolm, 2020), and less commonly the cannabis ruderalis plant. Various parts of these plants may be used: leaves, stems, seeds, and flowers/buds/nuggets (NIDA, 2019). Traditionally, cannabis use involved inhaling smoke either directly as a form of cigarette/cigar (nicknames include joint, blunt, roach, doobie) or through a filtration system (nicknames water pipe, bong). Recent use has included vaping or use of a vape pen/device, however a great deal of public health concern has emerged regarding vaping the psychoactive ingredients of cannabis. A warning released on October 4, 2019 stated:

In its continued efforts to protect the public, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is strengthening its warning to consumers to stop using vaping products containing THC amid more than 1,000 reports of lung injuries—including some resulting in deaths—following the use of vaping products…A majority of the samples tested by the states or by the FDA related to this investigation have been identified as vaping products containing THC. Through this investigation, we have also found most of the patients impacted by these illnesses reported using THC-containing products, suggesting THC vaping products play a role in the outbreak (seehttps://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/vaping-illness-update-fda-warns-public-stop-using-tetrahydrocannabinol-thc-containing-vaping)

In its continued efforts to protect the public, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is strengthening its warning to consumers to stop using vaping products containing THC amid more than 1,000 reports of lung injuries—including some resulting in deaths—following the use of vaping products…A majority of the samples tested by the states or by the FDA related to this investigation have been identified as vaping products containing THC. Through this investigation, we have also found most of the patients impacted by these illnesses reported using THC-containing products, suggesting THC vaping products play a role in the outbreak (seehttps://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/vaping-illness-update-fda-warns-public-stop-using-tetrahydrocannabinol-thc-containing-vaping)

The act of smoking cannabis has a number of nicknames, as well: toking, cheeching, blowing, firing one up, going loco, and others (see https://americanaddictioncenters.org/marijuana-rehab/slang-names). Mode of administration matters with cannabis. First, inhaling cannabis in smoke delivers the psychoactive chemicals fairly quickly to the brain. As discussed in previous modules, this has a profound impact on how a person “learns” to anticipate the effects and on the potential for developing a cannabis substance use disorder. Additionally, smoking/inhaling cannabis exposes the mouth, throat, and lungs to hundreds of chemicals present in the plant material or as additives, some of which may have long-term health implications (Begun, 2020).

Use of cannabis’ psychoactive ingredients in oils and extracts has recently become popularized. This includes consuming the products in food, as edibles (e.g. baked goods, candy, infused cooking oil or butter). The potential problem with edibles is that the action of the psychoactive ingredients is somewhat delayed since the product needs to be digested for absorption to occur. Thus, the psychoactive effects might not be experienced for 1-3 hours post-ingestion. If a person’s expectancy involves an immediate effect (as happens with the faster administration route of smoking), that person may continue to consume edibles and end up with an excessive dose when it does begin to take effect.

Use of cannabis’ psychoactive ingredients in oils and extracts has recently become popularized. This includes consuming the products in food, as edibles (e.g. baked goods, candy, infused cooking oil or butter). The potential problem with edibles is that the action of the psychoactive ingredients is somewhat delayed since the product needs to be digested for absorption to occur. Thus, the psychoactive effects might not be experienced for 1-3 hours post-ingestion. If a person’s expectancy involves an immediate effect (as happens with the faster administration route of smoking), that person may continue to consume edibles and end up with an excessive dose when it does begin to take effect.

Cannabis products are most often used alone; however, individuals may intentionally or unintentionally (laced) use them in conjunction with other substances such as alcohol, cocaine, or heroin. The combination of alcohol and cannabis products has a potentiating effect, meaning that the effects of either alone are heightened, as are their side effects. The combination of cannabis with heroin or other opioids, like alcohol, is also potentiating: the presence of heroin increases the potential for problems in breathing, loss of consciousness, or opioid overdose. The combination of cannabis with cocaine is antagonistic in the sense that one is relatively calming/sedating (cannabis) and the other an intense stimulant (cocaine). This is intended to soften some of the harsh effects of cocaine use. Cannabis may also be contaminated with other products—particularly when illegally supplied—including inert/inactive plant materials, fungus infested material, bacteria, or other chemicals.

Cannabis products are most often used alone; however, individuals may intentionally or unintentionally (laced) use them in conjunction with other substances such as alcohol, cocaine, or heroin. The combination of alcohol and cannabis products has a potentiating effect, meaning that the effects of either alone are heightened, as are their side effects. The combination of cannabis with heroin or other opioids, like alcohol, is also potentiating: the presence of heroin increases the potential for problems in breathing, loss of consciousness, or opioid overdose. The combination of cannabis with cocaine is antagonistic in the sense that one is relatively calming/sedating (cannabis) and the other an intense stimulant (cocaine). This is intended to soften some of the harsh effects of cocaine use. Cannabis may also be contaminated with other products—particularly when illegally supplied—including inert/inactive plant materials, fungus infested material, bacteria, or other chemicals.

How Commonly Cannabis is Used

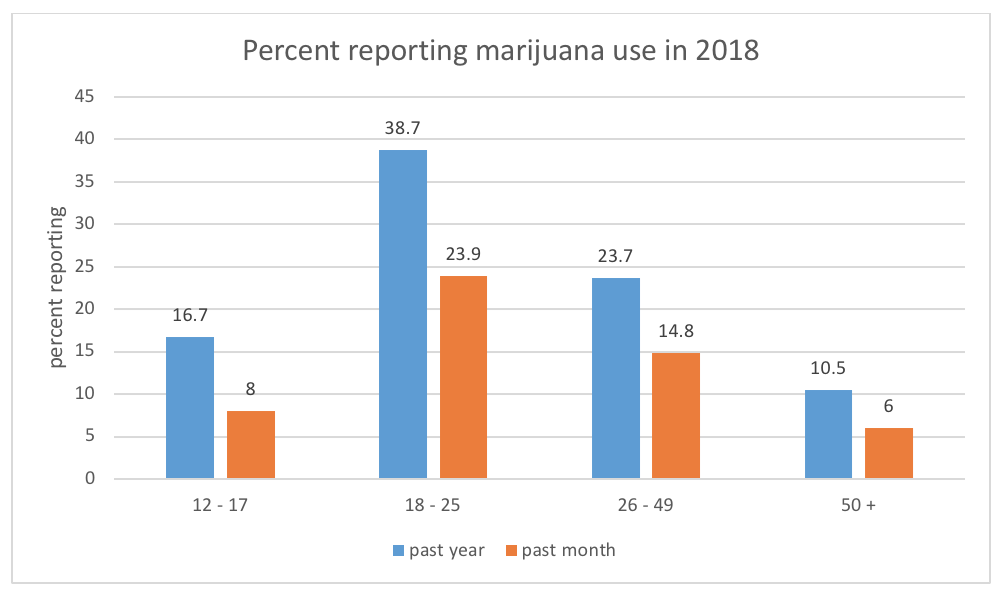

Other than alcohol, cannabis continues to be the most widely used psychoactive substance in the world: an estimated 188 million individuals used cannabis in 2017 (UNODC, 2019). According to the 2018 National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH; SAMHSA, 2019), 45.3% of individuals over the age of 12 years have used marijuana during their lifetime, 15.9% during the past year, and 10.1% during the past month. This graph depicts past year and past month use rates by age category: the rate is greatest among emerging adults aged 18-25. Still, marijuana use is not the “norm” in any of the age categories since many fewer than half engaged in this behavior.

Data suggest that marijuana use is more common among men than women: past year marijuana use was reported by 18.5% of males and 13.4% of females among persons aged 12 and older. Past year marijuana use was most often reported by individuals identifying as American Indian or Alaska Native (23.0%) or as being of two or more races (23.4%). The rate was lowest among individuals identifying as Asian (8.9%). This was more commonly reported by individuals who were not Hispanic or Latino (16.4%) compared to those self-identifying as Hispanic or Latino (13.6%), and slightly more commonly among Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (17.7%) and Black or African American (17.8) respondents than White respondents (16.5%).

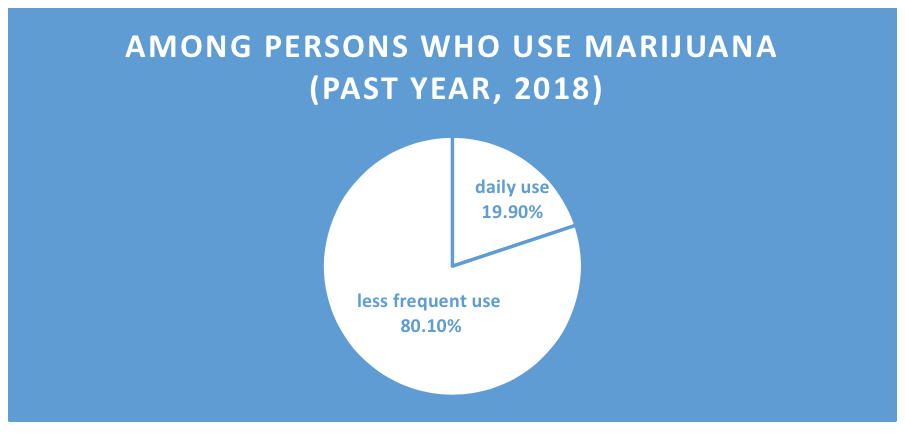

The frequency with which cannabis is used varies considerably. The 2018 NSDUH data (SAMHSA, 2019) indicated that the percentage of individuals aged 12 and older who in the past year used marijuana daily or almost daily was 3.2%; among individuals who used marijuana during the past year at all, 19.9% used it daily or almost daily. In other words, the vast majority of individuals who use marijuana do not use it daily or almost daily, but almost 8.7 million individuals do so (SAMHSA, 2019).

Cannabis Effects

Cannabis’ primary psychoactive chemical is Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol or tetrahydrocannabinol, both abbreviated as THC, which acts on cannabinoid receptors making up the endocannabinoid system throughout the body (NIDA, 2019a). THC is chemically very similar to the neurotransmitter anandamide, known to be involved in regulating mood, memory, appetite, pain perception, cognition, and emotions. Because of this chemical similarity, THC can bind to cannabinoid receptors usually activated by anandamide, thereby affecting similar functions and possibly interfering with normal functioning in the affected areas of the brain (NIDA, 2007). THC exposure initiates significant dopamine release in the areas of the brain with the highest concentrations of the involved receptors, particularly in brain areas responsible for behavioral reward systems. THC tolerance does develop in humans engaged in regular use (WHO, 2016).

The primary psychoactive effects of cannabis are intoxication, euphoria, relaxation, distorted sensory perception, impaired balance and coordination, and impaired cognitive functions or judgement; effects that potentially contribute to accidental injury (Begun, 2020). The short-range mental, psychological, and information processing effects (NIDA, 2019) include:

- altered sensory perception (e.g., colors seem brighter)

- altered sense of time

- altered mood

- impaired body movement/coordination/reflexive responses

- difficulty thinking and problem-solving (impaired cognitive functions)

- impaired memory

- hallucinations, delusional, and/or paranoid thinking (particularly at higher doses)

- depression

- anxiety

- possible suicidal thoughts

- temporary or persistent psychosis (highest risk with regular use of high potency products; individual vulnerability varies)

- worsening of symptoms among persons with schizophrenia.

Because cannabinoid receptors are distributed throughout the body, additional physical effects occur with use of cannabis products, including:

- respiratory/breathing problems (related to smoking cannabis, can be similar to smoking tobacco products) (NIDA, 2019a);

- increased heart rate (may increase risk of heart attack, with older individuals at greater risk) (NIDA, 2019a);

- cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (regular cycles of severe nausea, vomiting, and dehydration occurs in some individuals engaged in regular, long-term use) (NIDA, 2019); this seems paradoxical in that cannabis products may help reduce nausea in the short-term.

Long-term heavy cannabis use is associated with detectable functional and structural brain changes, particularly those involved in memory and cognitive performance—for example, an average of 8 IQ points lower compared to individuals who did not use cannabis regularly over a long period (WHO, 2016). Additionally, individuals who used cannabis 10 or more times before the age of 18 years were more than twice as likely to later receive a diagnosis of schizophrenia than individuals who did not use cannabis and there existed evidence of a dose-response relationship—heavier use was associated with greater risk (WHO, 2016). Their cannabis use appeared to have preceded the onset of schizophrenia symptoms, suggesting (but not conclusive) that the cannabis use likely was not an effort to self-medicate schizophrenia symptoms (WHO, 2016). Additionally, there exists a significant prevalence of co-morbid cannabis use disorder and other mental health disorders (WHO, 2016).

Because extrinsically introduced substances occur in greater concentrations and release greater amounts of the involved neurotransmitters than naturally occurring stimuli, their effects are experienced more intensely. This contributes to the potential for ongoing misuse of or addiction to these kinds of substances. Chronic cannabis use can result in development of a substance use disorder specified in the DSM-5 as cannabis use disorder, following the 11 diagnostic criteria identified in Module 2. The criteria include elements of recurrent use under physically hazardous conditions, tolerance, withdrawal, craving, greater use than intended, and other criteria similar to those in the general list of substance use disorder criteria. The DSM-5 also presents criteria for assessing:

- cannabis intoxication,

- cannabis withdrawal,

- cannabis intoxication delirium,

- cannabis-induced psychotic disorder,

- cannabis-induced anxiety disorder, and

- cannabis-induced sleep disorder.

Worldwide, cannabis use disorder was estimated to affect an estimated 4-8% of adults during their lifetime: approximately 13.1 million persons globally (WHO, 2016). In the 2018 United States National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) data, over 4.4 million individuals (1.6% of the population) aged 12 and older were estimated to meet criteria for a substance use disorder involving marijuana during the past year (NSDUH, 2019)—as much as 5.9% of the population of individuals aged 18-25 years. Although women have a lower prevalence of cannabis use disorder than men (0.14% versus 0.23%), women “exhibit an accelerated progression to cannabis-use disorder after first use and show more adverse clinical problems than men” (WHO, 2016, p. 11). This phenomenon is sometimes referred to as telescoping—the rate at which problems appear is collapsed into a shorter time frame.

Worldwide, cannabis use disorder was estimated to affect an estimated 4-8% of adults during their lifetime: approximately 13.1 million persons globally (WHO, 2016). In the 2018 United States National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) data, over 4.4 million individuals (1.6% of the population) aged 12 and older were estimated to meet criteria for a substance use disorder involving marijuana during the past year (NSDUH, 2019)—as much as 5.9% of the population of individuals aged 18-25 years. Although women have a lower prevalence of cannabis use disorder than men (0.14% versus 0.23%), women “exhibit an accelerated progression to cannabis-use disorder after first use and show more adverse clinical problems than men” (WHO, 2016, p. 11). This phenomenon is sometimes referred to as telescoping—the rate at which problems appear is collapsed into a shorter time frame.

Remember: the concentration of THC in different cannabis formulations varies markedly, which in turn means that the effects can vary widely, as well. While some efforts to develop THC content standards, THC and other chemical concentrations in different cannabis samples are not easily compared as in the case of standard drink equivalents with alcohol.

Driving under the influence.

Traffic injuries related to cannabis use are also of concern, particularly as more regions permit its medical and/or recreational use. The risk of car crash is estimated to double or triple with cannabis intoxication (WHO, 2016). Furthermore, the crash risk “increases substantially if cannabis users also have elevated blood alcohol levels, as many do” (WHO, 2016, p. 20). In the 2018 NSDUH data (SAMHSA, 2019), an estimated 11.8 million individuals aged 16 or older drove under the influence of marijuana during the past year; this figure is more than half the estimated 20.5 million individuals who drove under the influence of alcohol.

Traffic injuries related to cannabis use are also of concern, particularly as more regions permit its medical and/or recreational use. The risk of car crash is estimated to double or triple with cannabis intoxication (WHO, 2016). Furthermore, the crash risk “increases substantially if cannabis users also have elevated blood alcohol levels, as many do” (WHO, 2016, p. 20). In the 2018 NSDUH data (SAMHSA, 2019), an estimated 11.8 million individuals aged 16 or older drove under the influence of marijuana during the past year; this figure is more than half the estimated 20.5 million individuals who drove under the influence of alcohol.

Prenatal cannabis exposure.

Evidence is unclear as to the long-term developmental impact of prenatal exposure to cannabis. It is likely, however, that neurobehavioral and cognitive impairments, as well as alternations in the dopamine neurotransmitter system of some brain regions, are more common among children prenatally exposed to cannabis (WHO, 2016). Negative effects of prenatal cannabis exposure “may not become apparent until later in development. It is, therefore, essential to follow up cannabis-exposed children long into adolescence” (WHO, 2016, p. 16).

Evidence is unclear as to the long-term developmental impact of prenatal exposure to cannabis. It is likely, however, that neurobehavioral and cognitive impairments, as well as alternations in the dopamine neurotransmitter system of some brain regions, are more common among children prenatally exposed to cannabis (WHO, 2016). Negative effects of prenatal cannabis exposure “may not become apparent until later in development. It is, therefore, essential to follow up cannabis-exposed children long into adolescence” (WHO, 2016, p. 16).

Cannabis, Cannabinoids, and Cannabidiol

As previously noted, cannabis refers specifically to products derived from the cannabis plants of the sativa, indica, or ruderalis type (Malcolm, 2020). The term cannabinoid refers to a diverse range of chemicals structurally similar to THC and that act on the same cannabinoid receptors in the human body (UNODC, 2018; WHO, 2016). Many of these are either genetically modified versions of cannabis plants or laboratory manufactured synthetic products; endocannabinoids are produced naturally in the human body (WHO, 2016). Modified and synthetically produced cannabinoids may have many times greater relative dose exposure than those occurring naturally, and as a result, potential harm with their use is amplified (Malcolm, 2020). For example, you may hear about Spice or K2: these are synthetic cannabinoids produced by spraying plant material (not necessarily cannabis) with psychoactive chemicals. Thus, Spice and K2 tend to be many times more concentrated and bind to the cannabinoid receptors more intensely than cannabis alone—there is no way of knowing what or how much active ingredient is involved or what other toxic substances might be included in these products. “Between 2011 and 2017, U.S. poison control centers received more than 31,000 calls related to synthetic cannabinoid effects” (https://www.webmd.com/mental-health/addiction/news/20180910/k2-spice-what-to-know-about-these-dangerous-drugs).

Cannabinoids have recognized medical uses recognized in many, but not all, countries: cannabis remains a Schedule I drug in the U.S. DEA classification system because of its high potential for abuse and the absence of their recognized medical uses in the U.S. This, however, may be changing as increasing evidence emerges supporting its efficacy in treating numerous physical and mental health conditions.

Cannabidiol (CBD) is a cannabinoid naturally occurring in cannabis plants, including hemp (low THC-containing cannabis varieties), although it can also be synthetically manufactured (WHO, 2018). In countries outside of the United States, CBD has medical uses in treatment of several medical conditions; its use is under study for approval as a medical treatment in the United States, as well. CBD does not produce the psychoactive effects seen with THC, seems not to have the abuse potential seen with THC, and appears not to affect heart rate or blood pressure under normal conditions—though it may reduce both under conditions of stress (WHO, 2018). Very preliminary research suggests that CBD may prove helpful in treating opioid, cocaine, cannabis, and tobacco addiction, but “considerably more research is required to evaluate CBD as a potential treatment” (WHO, 2018, p. 19). At this time, CBD remains in Schedule I among controlled substances in the United States.

Cannabidiol (CBD) is a cannabinoid naturally occurring in cannabis plants, including hemp (low THC-containing cannabis varieties), although it can also be synthetically manufactured (WHO, 2018). In countries outside of the United States, CBD has medical uses in treatment of several medical conditions; its use is under study for approval as a medical treatment in the United States, as well. CBD does not produce the psychoactive effects seen with THC, seems not to have the abuse potential seen with THC, and appears not to affect heart rate or blood pressure under normal conditions—though it may reduce both under conditions of stress (WHO, 2018). Very preliminary research suggests that CBD may prove helpful in treating opioid, cocaine, cannabis, and tobacco addiction, but “considerably more research is required to evaluate CBD as a potential treatment” (WHO, 2018, p. 19). At this time, CBD remains in Schedule I among controlled substances in the United States.

Cannabinol (CBN) is a cannabinoid with weak psychoactive potential, much less than THC of which it is a metabolite (breakdown product). The term hemp refers to cannabis varietals low in THC, thus are considered non-intoxicating. Interest in CBN is more aligned with potential medical uses related to some observed effects on immune and inflammatory processes rather than with psychoactive potential. Globally, hemp also is produced and used in many ways related to its physical characteristics (e.g., textiles, construction and insulation materials, cosmetics, pulp/paper-like products, animal bedding, insect repellant, biodegradable landscape matting, cooking oil, fuel, and others https://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/ncnu02/v5-284.html).

STOP & THINK

Review the nine statements below and click on the number in front of only those that you believe are true, accurate statements based on what you read in this chapter.