Ch. 2: Prevention and the Continuum of Care

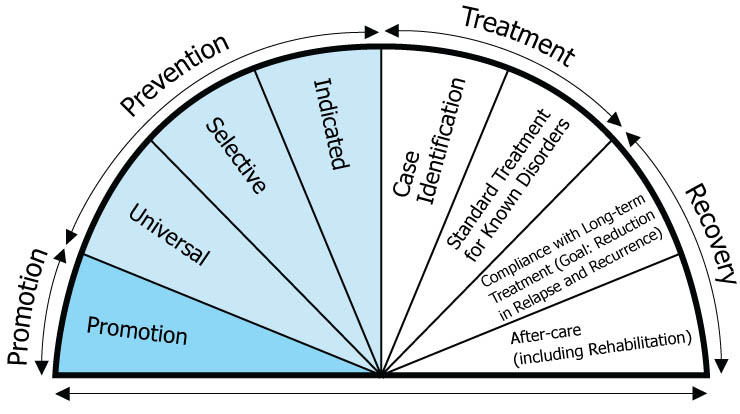

The theories explored in our various modules so far have implications for the prevention of substance misuse and substance use disorders, including (but not limited to) delaying or preventing substance use initiation. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) produced a Fact Sheet through the Center for the Application of Prevention Technologies discussing prevention as part of a behavioral health continuum of care. The Fact Sheet includes a diagram built on the foundational work presented in an earlier Institute of Medicine report diagramming the relationship between prevention, treatment, and maintenance in mental health care (IOM, 1994). This continuum of care framework is applicable to intervening around substance misuse and substance use disorders, and with the addition of health promotion embraces much of what is important in the recovery support services movement (Bersamira, in press).

This is how the Fact Sheet described the different “wedges” of the spectrum:

- Promotion: “These strategies are designed to create environments and conditions that support behavioral health and the ability of individuals to withstand challenges. Promotion strategies also reinforce the entire continuum of behavioral health services” (SAMHSA, n.d., p. 2). The promotion strategies described in the SAMHSA Fact Sheet include interventions that address resilience factors considered in our Chapter 1 discussion; strengths-based strategies designed to promote well-being and positive functioning.

- Prevention: “Delivered prior to the onset of a disorder, these interventions are intended to prevent or reduce the risk of developing a behavioral health problem, such as underage alcohol use, prescription drug misuse and abuse, and illicit drug use” (SAMHSA, n.d., p. 2).

-

- Universal prevention refers to interventions delivered to the general population without differentiating between persons at different risk levels. For example, schools may deliver drug awareness and resistance education (DARE) programming to all students regardless of their vulnerability/risk constellation. Mass media campaigns are another example of universal efforts. In much of the prevention literature, the term “primary” prevention is used to describe efforts that occur before any sign of the target problem appear—universal prevention interventions are often applied.

Selective prevention is more targeted than universal, and these interventions would be directed towards populations identified as having a potential somewhat greater than the general population for developing the focal problem. For example, it might be aimed at youth who live with one or more parents/family members engaged in substance misuse. In some prevention literature, the term “secondary” prevention is used to describe efforts that occur before the target problem appears and delivered to populations deemed to be “at risk” of the problem emerging—this could involve selective prevention interventions. Selective prevention is akin to a severe weather “watch” to keep a watchful eye on things, rather than a “warning” that the event is on the verge of happening.

Selective prevention is more targeted than universal, and these interventions would be directed towards populations identified as having a potential somewhat greater than the general population for developing the focal problem. For example, it might be aimed at youth who live with one or more parents/family members engaged in substance misuse. In some prevention literature, the term “secondary” prevention is used to describe efforts that occur before the target problem appears and delivered to populations deemed to be “at risk” of the problem emerging—this could involve selective prevention interventions. Selective prevention is akin to a severe weather “watch” to keep a watchful eye on things, rather than a “warning” that the event is on the verge of happening.

- Indicated prevention is even more targeted, delivered to populations/groups of individuals exhibiting/expressing warning signs foreshadowing development of the focal problem. For example, to prevent alcohol use disorder interventions might be directed to youth/emerging adults engaged in binge drinking, preventing this behavior from becoming heavy drinking and a substance use disorder. As the focus increases, preventive interventions may become increasingly resource-intensive and intrusive which makes the focus beneficial. A great deal of effort and resources would be wasted if these intensive interventions were delivered to a large portion of the general population unlikely to develop the problem anyway. In some prevention literature, the term “tertiary” prevention is used to describe efforts that occur early in emergence of the target problem—this could involve indicated prevention interventions or early intervention in the form of treatment. Indicated prevention is akin to a severe weather “warning” as a more imminent threat than a “watch.”

- Treatment: “These services are for people diagnosed with a substance use or other behavioral health disorder” (SAMHSA, n.d., p. 2). Unlike prevention, treatment services are designed to identify individuals experiencing or exhibiting the focal problem—preferably as early in its development as possible, before it becomes increasingly severe and more difficult to treat. Ideally, the treatment services delivered are those with the strongest evidence supporting their use under the circumstances involved.

- Recovery (the Fact Sheet reverts to the term “Maintenance” in the text, despite their Recovery label on the diagram): “These services support individuals’ compliance with long-term treatment and aftercare” (SAMHSA, n.d., p. 2). The diagram mentions long-term adherence to treatment as fitting into this category, which may or may not reflect what happens during/following treatment for substance use disorder. For example, engaging in mutual help/support programming (such as Alcoholics Anonymous/AA, Narcotic Anonymous/NA, SMART Recovery, Women for Sobriety, LifeRing, Celebrate Recovery, and others) may be a part of both the treatment continuum and the recovery/maintenance continuum.

Additional points made in the Fact Sheet include the fact that interventions do not necessarily fit into only one category. For example, a universal prevention intervention may take the form of health promotion. The term relapse prevention also may introduce a bit of confusion here: preventing a relapse to the old behavior is not usually considered part of the prevention continuum; it is usually considered part of the recovery/maintenance portion of the continuum of care.

Additionally, the fact sheet suggests that risk and protective factors may be both correlated and cumulative. On one hand, a person with one vulnerability or risk factor may be more likely to have multiple vulnerability and risk factors (positively correlated). This person also may have fewer resilience or protective factors, as well (negatively correlated with risk/vulnerability). On the other hand, a vulnerability or risk factor introduced early on may have developmental impacts that compound the person’s vulnerability or risk over time. For example, being known as someone who uses alcohol, tobacco, or other drugs as a young adolescent might lead to that person being labeled, shunned, and stigmatized by peers. This, in turn, leaves that person vulnerable to social isolation and being attracted to a “deviance promoting” peer group, which compound the vulnerability and risk for substance misuse. The risk and vulnerability load just keeps getting heavier and heavier. Risk and vulnerability factors influence one another, underscoring “the importance of (1) intervening early, and (2) developing interventions that target multiple factors, rather than addressing individual factors in isolation” (SAMHSA, n.d., p. 7).

Just as treatment interventions need to be developmentally appropriate, so do prevention interventions. Children and adolescents are qualitatively different from adults; simplifying or “dumbing down” interventions for adults is not sufficient adaptation for younger populations. Because the risk and vulnerability factors are different at different periods of the life cycle, preventive efforts need to be tailored to what is relevant and salient at different periods (SAMHSA, n.d.). Preventive interventions also need to be appropriate for the vulnerability/risk mechanisms operating at different life periods. For example, if the concern is ease of access to substances, intervention might be targeted at the neighborhood/community or policy level rather than individuals; if the concern is to build initiation resistance skills, the intervention might be aimed at the individual level.

Just as treatment interventions need to be developmentally appropriate, so do prevention interventions. Children and adolescents are qualitatively different from adults; simplifying or “dumbing down” interventions for adults is not sufficient adaptation for younger populations. Because the risk and vulnerability factors are different at different periods of the life cycle, preventive efforts need to be tailored to what is relevant and salient at different periods (SAMHSA, n.d.). Preventive interventions also need to be appropriate for the vulnerability/risk mechanisms operating at different life periods. For example, if the concern is ease of access to substances, intervention might be targeted at the neighborhood/community or policy level rather than individuals; if the concern is to build initiation resistance skills, the intervention might be aimed at the individual level.

The SAMHSA Fact Sheet presented a set of tables of risk and protective factors for substance use disorder mapped to broad developmental period. These tables can help inform prevention strategies and used O’Connell, Boat, & Warner (2009) as their source. Their tables are replicated [with minor modifications] here and represent general mental health prevention goals at early ages.

|

Infancy and Early Childhood Competencies: Infants begin understanding their own and others’ emotions, to regulate their attention, and to acquire functional language |

|

|

Risk Factors |

Protective Factors |

|

|

|

Middle Childhood Competencies: Children learn how to make friends, get along with peers, and understand appropriate behavior in social settings |

|

|

Risk Factors |

Protective Factors |

|

|

|

Adolescence Competencies: Adolescents focus on developing good health habits, practice critical and rational thinking, seek supportive relationships [and extend autonomy skills] |

|

|

Risk Factors |

Protective Factors |

|

|

|

Early [Emerging] Adulthood Competencies: Individuals learn to balance autonomy with relationships to family, make independent decisions, and become financially independent |

|

|

Risk Factors |

Protective Factors |

|

|

Harm Reduction as Prevention

You may recall learning about Harm Reduction as a policy strategy way back in our first course module—that the goal is to reduce potential harms to individuals, families, communities, and society associated with substance use/misuse/use disorder, even if the substance use behavior does not end. Harm reduction policies, therefore, represent a type of prevention effort—preventing the associated harms. Harm reduction approaches are not limited to policy efforts: they also are applied at the individual level. For example, strategies to: reduce an individual’s risk of infection, accidental injury, or disease exposure associated with substance misuse; reduce the chances of accidental overdose; or protect from criminal/sexual violence associated with substance use.

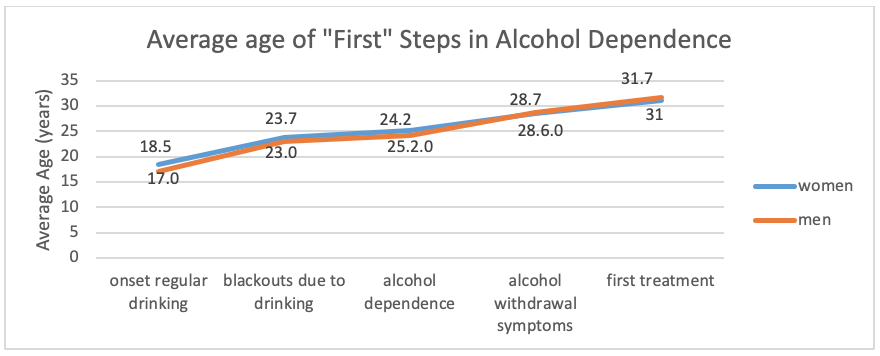

Another possible interpretation of prevention is intervention to slow, halt, or reverse progression from substance use to substance use disorder. As you learned in Module 4, there exists evidence suggestive of a developmental course of substance use disorder/addiction, even if there also exists variability in the course and its expression. Consider the developmental picture of average ages at which different events occurred in the lives of a group of individuals in treatment for alcohol use disorder (Schuckit, et al.,1998). Notice how many years (8!) were present between the average age at when blackouts due to drinking first occurred and when these men and women entered into treatment for alcohol use disorder: a harm reduction strategy might involve shortening this time span to reduce the physical, social, legal, and other harms that might accrue during that lengthy time span.

Prevention Examples

In their book chapter about preventing alcohol and drug problems, McNeece and Madsen (2012) identified a host of efforts and strategies, including at the policy level. At this point, you should turn to the McNeece and Madsen (2012) chapter to become familiar with how they describe primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention (aligned with universal, selective, and indicated prevention) and their review of the following types of prevention efforts:

- Public Information and Education

- Programs Directed at Children and Adolescents

- Programs Directed at College and University Students

- Service Measures

- Technologic Measures

- Legislative, Regulatory, and Economic Measures

- Family and Community Approaches

- Spirituality and Religious Factors

- Cultural Factors

Don’t forget to return to this coursebook for Chapter 3!