Ch. 3: Theories of the Psyche

The next set of theories to consider can be loosely grouped together under the heading of theories of the psyche—capturing the essence of who a person “is.” Under this heading, we consider psychodynamic, attachment, personality, and psychopathology theories related to substance misuse and substance use disorder. These represent some of the historically earliest psychological models used to explain the phenomenon of addiction.

Psychodynamic Theory

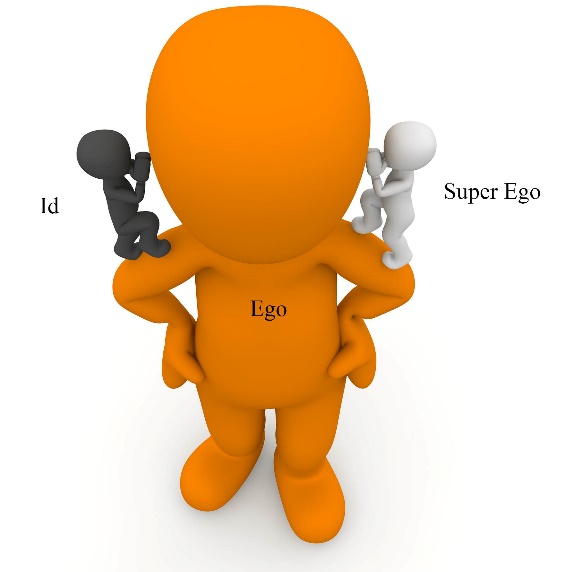

In a psychodynamic theory interpretation, addiction is not viewed as being a disease in and of itself but as a symptom of intra-psychic conflict, unresolved psychological tension, or psychological turmoil. On one hand, a person may experience urges to express emotions by behaving in ways that might not be socially acceptable. The urge to handle frustration or anger through aggression and violence are examples of this side of the equation, born in the primal aspects of personality (called the Id). The Id is not just negative, it includes positive feelings, too—think of a really young puppy as a ball of Id—it acts as it feels, positively or negatively, totally in the moment, with no filter, no restraint.

In a psychodynamic theory interpretation, addiction is not viewed as being a disease in and of itself but as a symptom of intra-psychic conflict, unresolved psychological tension, or psychological turmoil. On one hand, a person may experience urges to express emotions by behaving in ways that might not be socially acceptable. The urge to handle frustration or anger through aggression and violence are examples of this side of the equation, born in the primal aspects of personality (called the Id). The Id is not just negative, it includes positive feelings, too—think of a really young puppy as a ball of Id—it acts as it feels, positively or negatively, totally in the moment, with no filter, no restraint.

On the other hand, over time and through repeated learning encounters with the physical and social world, a person (and hopefully puppies) develop enough experience to understand and appreciate that acting aggressively or violently is not socially acceptable and that this behavior is a poor choice. In other words, the super-ego has stepped in to editorialize about the Id response to emotions. This is where sentiments like guilt and shame come into play, helping reign in socially unacceptable behavior choices.

The ego, which develops over time through experience, learning, and social learning, becomes the manager. The ego is faced with the challenge of serving as a referee between strong “act” urges coming from the Id and strong “inhibit” pressures from the Super Ego. As a result, the ego can create appropriate balance between pleasure and control, where emotions and urges are expressed in acceptable ways. The ego also helps prevent someone from acting unwisely or in an unsafe manner.

In this psychoanalytic or psychodynamic model, a person may resolve some of this Id-Superego tension by using alcohol or other drugs for their ability either to “numb” feelings that are triggering the Id response or to silence the super-ego, put it to sleep, thereby removing the unpleasant, tension-filled experience of conflict. Sometimes individuals in conflict feel the need to quiet the “voices” that are always “yelling” in their minds. Additionally, psychoanalytic or psychodynamic theory might suggest that an individual who has experienced trauma might use substances as a means of “numbing” the powerful negative feelings experienced as a result of reminders of the past trauma experience. This is not the only way the theory has been applied to substance use, however.

Orality. Yet another psychoanalytic interpretation of addiction, particularly for cigarette smoking and drinking alcohol, is one related to the concept of oral fixation.

A normal part of infant development involves exploring the world orally, through the taste and touch sensations of the mouth. In psychoanalytic theory, it is part of the normative course of development that a person’s libidinal energies become localized at a specific zone of the body at different periods of development. Libido does not only refer to a person’s sexual drive—this is true during the developmental period when the libidinal energy localizes in the genital zone.

Earlier in development these libidinal energies localize in the oral zone—the mouth and mouth parts. Stimulation of the oral zone feels good because it relieves the tension in that area caused by the localized libido. Orality is a period of infancy—we expect to see babies using their mouths to explore the world.

According to psychoanalytic theory, if something goes wrong with development at this early orality phase of development then a portion of libidinal energy becomes “stuck” in the oral zone. The person will spend a lifetime trying to satisfy their need for oral stimulation—putting things in the mouth, chewing, or sucking on things. In theory, a need to smoke cigarettes, hookah, e-cigarettes, or cigars—putting them in the mouth and all the ritual that goes into smoking them—and maybe a need to drink alcohol, could represent efforts to curb demands from the trapped libido. Logically, then, a person should be able to substitute one oral tool for another—in other words, chewing gum or drinking from water bottles should resolve a “need” to smoke or to drink alcohol. It is not so simple, though—the tool in the form of cigarettes, hookah, e-cigarettes (vaping) or alcohol comes to cause some needs of its own.

Attachment Theory

An attachment theory of addiction is not far removed from psychoanalytic and psychodynamic theory explanations. As explained in the early works of John Bowlby, infants and young children, in the normative course of development, form attachment relationships with others central to their physical and emotional survival—parents, siblings, caregivers, pets, and even special “transitional objects” (like a blankie or stuffed animal). These psychological attachments allow someone to have the sense of security in a great big, unpredictable world. Within these attachment relationships, individuals begin to make sense of their social world.

Sometimes, attachment relationships are disrupted or dysfunctional. They either fail to form, are broken once formed, or develop as insecure and unstable attachments. According to attachment theory, a person experiencing attachment issues is likely to experience significant “holes” in their emotional and personality development. The world does not seem like a safe, predictable, reliable place to exist, nor are there safe, predictable people on whom the person can rely. Their understanding of and relationship to the world is likely to have significant gaps.

Sometimes these individuals describe themselves as being “full of emptiness.”

As in the case of the psychoanalytic model, this person may come to rely on drugs or alcohol as a means of coping with these gaps, and the associated negative feelings and sense of detachment. It might “numb” the psychic pain for them. The drinking or drug-taking social environment itself may become what they use to fill the emptiness—it is not necessarily the alcohol or drugs at first, but the drinking or drug-taking situations that start the pattern.

Based on these models, the type of intervention that we have available involves attempting to address the root psychic conflicts or deficits and repair the damage to the psyche. Here we are going to try to help the person become whole, to find a way to resolve their internal conflicts and become whole or to fill the empty void and become whole. This is the therapeutic goal of many forms of psychotherapy. The preventive strategy is to help create environments during early infant, child, and adolescent development that nurture the person and help them develop healthy super ego and ego strengths. Furthermore, throughout the life cycle, prevention involves avoiding the disruption of attachment relationships and exposure to traumatizing experiences.

Self-Medication Theory

The self-medication theory has, in part, been explained in our discussion of psychodynamic and attachment theory. As discussed, an individual may choose to use substances to quiet psychic conflict, fill emotional emptiness, and/or escape the emotional aftermath of trauma. One thing known about the population who misuse alcohol or other substances is that the incidence of their having experienced injury, trauma, or abuse is much higher compared to the rest of the population. For example, in a study of Vietnam veterans, among individuals meeting criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), 73% also met substance use disorder criteria (Kulka, et al., 1990). Among these veterans, men with PTSD were two times more likely and women with PTSD were five times more likely to also experience a substance use disorder than were their counterparts without PTSD.

Among civilian populations, the experience of trauma is often associated with substance use disorder, particularly among women: in one United Kingdom study, among 146 women engaging in substance misuse, 90% had experienced trauma in the form of intimate partner violence, traumatic grief, sexual abuse, physical abuse, bullying, or neglect (Husain, Moosa, & Khan, 2016). In an Australian sociological study of youth and substance abuse, initiation of substance use was associated with childhood trauma, leaving school (dropout), separation from family, and homelessness, as well as unemployment (Daley, 2016), and a great deal of evidence relates adverse childhood events (ACES) with substance misuse and substance use disorders, as well (Sartor et al., 2018).

“My whole life went downhill. I was abused, and used alcohol to escape the pain. I became horrible to myself and everyone around me. I honestly didn’t care what happened anymore” (quoted in Najavits, 2009, p. 290).

Self-medication theory is somewhat controversial. The prior examples do not demonstrate a causal relationship whereby self-medication theory is proven; the theory remains a possible explanation for at least some of the co-occurrence. Sometimes trauma events precede substance misuse. Other times, traumatic events occur during a period of substance misuse or after substance misuse was initiated. Self-medication may have more to do with “treating” physical pain from injury or chronic illness than managing psychic or emotional pain. In addition, individuals may use substances to self-medicate a host of other mental health concerns—attention deficit disorder, anxiety, depression, or stress, for example. Clinicians often encounter individuals experiencing substance use problems who have one or another form of chronic pain or depression or anxiety or attention deficit disorders with or without hyperactivity or other problems they believe the substance use can relieve. While this might be a reason why some individuals initiate use of one or more substances, it may not explain how the substance use becomes substance use disorder. There are other reasons why individuals initiate substance use, and evidence on this theory is mixed.

A scholar named Lisa Najavits was one of the first to develop intervention approaches specifically designed in an integrated manner to address trauma experiences and substance abuse. She published a book called Seeking Safety that is used today as the basis of programs all over the world. How does this relate to the self-medication theory? Since many individuals who misuse alcohol, illicit drugs, or prescription drugs may be attempting to “treat” their own physical and/or psychological pain, finding healthful strategies for doing so might facilitate recovery from substance misuse and substance use disorder. As much as the classic quote about a self-treating physician having a fool for a patient may be true, how more true could it be when individuals in the general population are self-medicating?

Personality and Psychopathology Theory

Past clinical literature discusses a phenomenon called the “addictive” personality. This concept presumes the existence of a constellation of specific personality traits characterizing individuals who develop substance use disorders (or addiction). In theory, these individuals are predisposed to develop a substance use disorder (or addiction) by virtue of possessing these personality traits—in much the same way genetics may predispose someone to develop a substance use disorder. The question becomes: is there such a thing as an “addictive” personality?

These days, the idea of an addictive personality is considered somewhat dated as it is not well supported by evidence. While there exist some traits or characteristics commonly observed among groups of individuals who experience substance use disorders, the evidence does not support there being a universal set of personality traits or personality type associated with addiction/substance use disorders. Evidence for the existence of an “addictive personality” type does not exist (per Szalavitz, 2016 citing an interview with George Koob, director of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism).

These days, the idea of an addictive personality is considered somewhat dated as it is not well supported by evidence. While there exist some traits or characteristics commonly observed among groups of individuals who experience substance use disorders, the evidence does not support there being a universal set of personality traits or personality type associated with addiction/substance use disorders. Evidence for the existence of an “addictive personality” type does not exist (per Szalavitz, 2016 citing an interview with George Koob, director of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism).

What we know is that pretty much any person can become addicted to something if the right (or, in this case the wrong) circumstances come together. Some individuals may be more vulnerable or at a higher risk of addiction to certain substances, but the potential exists for anyone depending on circumstances. We also know that the circumstances vary somewhat for different types of substances—the vulnerability and risk for developing alcohol use disorder is not the same as for developing addiction to nicotine or cocaine or opioids or cannabis.

On the other hand, some personality traits or characteristics are shared by many (not all) persons experiencing a substance use disorder/addiction. For example, in her book challenging the addictive personality, Szalavitz (2016) reported research concluding that 18% of persons experiencing an addiction also exhibited “a personality disorder characterized by lying, stealing, lack of conscience, and manipulative antisocial behavior” and that this 18% rate was more than four times the rate observed in the general population. However, arguing against this being the hallmark of an addictive personality are the observations that (1) this leaves 82% of individuals experiencing addiction not expressing this personality disorder and (2) individuals with this personality disorder do not all develop addiction. In other words, the person experiencing addiction is not a separate type of person from the rest of the population. This kind of result is common across many studies of addictive personality traits—the population of individuals experiencing addiction/substance use disorders is tremendously diverse and heterogeneous across many demographic, personal history, and personality factors.

There exists some evidence to suggest that certain temperament or personality characteristics are associated (correlated) with a higher probability of initiating substance use, especially early initiation of alcohol or tobacco use during adolescence. For example, studies emphasize the increased odds of using/misusing substances among adolescents who have angry-defiant personality types, as well as the “thrill seeker” personality type (sometimes called the “Type T personality”). Or, evidence indicates that “young people diagnosed with conduct disorders and other oppositional disorders are also at higher risk for developing substance use disorders in adolescence and early adulthood,” as is also true of individuals with bipolar and major depressive mood disorders (Cavaiola, 2009, p. 721).

Again, these personality and psychopathology traits are shared by individuals who develop and do not develop addiction or substance use disorders—they are not traits specific to addiction. Furthermore, it is difficult to determine where the behaviors (e.g., antisocial) preceded the addiction and where the addiction preceded the behaviors—meaning that the trait is not a cause of the addiction but a consequence (Cavaiola, 2009).

As a result of newer research methods and ways of analyzing data, some of the earlier correlational studies of personality traits have fallen out of favor. Thus, there is less emphasis these days on personality theory and theories of an addictive personality. In a way, this is a positive development because personality theory leaves very little in the way of intervention tools: personality traits are very resistant to change!