Chapter 3: Theories and Human Trafficking

ABSTRACT

Theories inform the way many disciplines approach research, practice, and knowledge building. The field of social work as a whole borrows theories from a number of fields including medicine, psychology, and sociology. In this chapter, a few basic theories common in social work research will be discussed. Specifically, the theories will be explored in relation to human trafficking and human rights violations.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, the student will be able to:

- Recognize common theories applied to human rights violations and human trafficking

- Apply theories to understand intervention development strategies

Key Words: General Systems Theory, Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory,

Conflict Theory, Functional Theory, Labeling Theory, Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

GLOSSARY

General systems theory: A theory based on interactions between varying sizes of systems in maintaining equilibrium through inputs, throughouts, outputs, and feedback loops

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory: A theory used to understand the bidirectional influence of varying levels of ecological systems on an individual

Conflict theory: A theory aimed at understanding oppression and power structures through examining structural conflict

Structural-functional theory: A theory used to understand society by exploring the functional role that all parts play in a society; this theory is also referred to as functionalism and structural functionalism

Labeling theory: A theory that explores the behavioral implications of labeling a person deviant or criminal

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: A pyramid-style model that sets out the needs of all individuals in a hierarchical manner

Chapter on Theories

In this section, the authors discuss a range of theories to provide a context for human trafficking. Theories include general systems theory, Bronfennbrenner’s ecological systems theory, conflict theory, structural-functional theory, labeling theory and Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

General Systems Theory & Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory

General systems theory was introduced to the social work field in the late 1950’s and early 1960’s and was based on a biological model (Kondrat, 2013). The biologist credited with general systems theory is Bertalanffy, who was concerned about the practice of studying phenomena as isolated entities instead of players in feedback systems and hierarchical orders (Kondrat, 2013). The social work understanding of general systems theory, much like the name suggests, is a theory based on understanding a system–a series of components that interact with and influence one another (Berg-Weger, 2005). General systems theory considers all systems as subsystems of other systems, and considers large systems as environments for other systems, thus always exploring the flow and impact of different systems between and against each other (Forder, 1976). General systems theory has mostly been replaced by Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model, but is still used in some areas of social work (Kondrat, 2013).

The systems that influence the individual in the social work perspective can be social or physical entities–family, culture, workplace, communities, etc. (Berg-Weger, 2005). The purpose of using general systems theory in social work is to begin understanding the “person in environment”, which is the perception of each individual as a participant influenced by larger physical, social, and environmental systems (Berg-Weger, 2005). Taking a person in environment approach gives social workers more opportunities to intervene—understanding the various systems in place that allow or perpetuate a problem creates more intervention points. However, arguments against the use of general systems theory in social work have included concerns about the model not accounting for values and ideology as well as concerns about application of the model to the complexities of the human experience (Kondrat, 2013; Shriver, 1998). General systems theory assesses the relationship of inputs on the individual, or throughput, and the following consequences, or outputs, in a feedback loop relationship that is aimed at some type of regulation (Skyttner, 1996). General systems theory in social work shifted the focus on interventions to understanding the transactions that happen between an individual and their larger systems (Kondrat, 2013).

There is some debate about the differences between general systems theory and ecological systems theory (Schriver, 1998). A critique of general systems theory in its application to social work is that it focuses on elements of an individual’s life as components of a system, which comes with an assumption of equilibrium–both that the system needs it and that the system can achieve it (Leighninger, 1977). Ecological systems theory also explicitly defines the environmental systems as including nonliving elements, something sometimes assumed but never explicitly stated in general systems theory (Shriver, 1998). Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory mostly replaced general systems theory in the late 1970s and early 1980s and is a continuation of understanding the person in environment (Kondrat, 2013). The ecological systems theory explores the relationship of an individual’s environment on their behavior, whereas general systems theory seeks to understand the changes an individual’s system undergoes when a change in a subsystem is made (Berg-Weger, 2005).

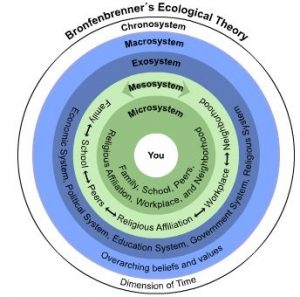

Bronfenbrenner argues that people develop within five systems of influence. They include the: microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem, and chronosystem (Bronfenbrenner, 1994). The model is set up as a growing set of nesting circles, with each larger circle encompassing a larger system, and each circle influencing each other bidirectionally. Newer versions of the ecological model sometimes called the chronosystem is a policy-level-system, showing how policy and greater institutional level processes impact a person’s smaller systems (Sallis & Owen, 2015). This means that at the policy and institution levels, changes can influence how a person lives and operates because they have to develop and mature with constraints or supports from these powers. The individual is at the center of these five systems, and the ways in which they all interact to influence the individual is the basis of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory. See Figure A.

Figure A. Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Theory

https://sites.google.com/site/dsmktylenda/content/bronfenbrenner-s-ecological-theory

In relation to human trafficking and human rights, both general systems theory and Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory are often already present and applied when thinking about interventions, even if not explicitly. Clawson and colleagues (2003), completed a needs assessment for trafficking victims and agencies that provide services to victims. In their assessment, they looked at the inputs of current efforts and services available via the throughput of victim care. The outputs, or the current state of victim care as a result of the services available, were analyzed in relation to how they can feed back into informing future efforts and services available to victims. Since it has been several years since the analysis, a general systems theory approach could be taken again to look at current inputs, influenced by previous outputs and feedback loops, on victim care. Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory can be seen when evaluating risk factors for human trafficking and human rights violations. Poverty, a history of abuse and neglect, substance use issues, political instability, homelessness, and marginalized identities have been highlighted in other chapters as risk factors for an individual to become a human trafficking victim. Risk factors can be understood within the ecological systems model, which assists social workers in identifying areas for intervention and prevention for at-risk populations.

Conflict Theory & Structural Functional Theory

Conflict theory emerged in the late 19th century from Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels (Hutchison, 2013). Conflict theory explores power structures and power disparities–that is, how power differentials affect social inequality (Hutchison, 2013; Parillo, 2012; Rӧssel, 2013). Conflict theory serves as the opposite to functional theory (Shriver, 1998; Parillo, 2012), which will be explored next. Conflict theory operates on the premise that humans are self-interested and competitive by being forced into conflict over scarce resources and wealth (Rӧssel, 2013; Shriver, 1998). Within conflict theory, wealthier classes are able to maintain power over lower-income and ethnic minority groups by allowing oppressed groups to believe that the advancement of another oppressed group will be to their detriment; therefore oppressed groups assist in the oppression of each other in the hopes that they will be the ones to advance (Parillo, 2012). From this perspective, social order exists through coercion of oppressed and less powerful groups by the ruling and more powerful classes (Shriver, 1998). Similarly, social change occurs through a conflict, evoking human response in the political, economic, and cultural spheres (Hutchison, 2013). There is a lot of social work practice that evolves from addressing social injustice through conflict theory. Early social work efforts at eliminating oppression of immigrants, women, and children were based in conflict theory, and efforts continue today through development of empowerment strategies for nondominant groups (Hutchison, 2013). However, critics of conflict theory say that the theory does not account for social unity and shared values, stating the theory is too radical (Parillo, 2012).

Structural-functional theory or functional theory states that every part of a society serves a function in maintaining the solidarity and stability of the whole (Parillo, 2012). Ideally, all the parts of a society maintain equilibrium and a state of balance under perfect conditions (Parillo, 2012). However, when problems arise, it is because a part of the social system has become dysfunctional; usually caused by some type of rapid change, which the other parts of the system are not able to adjust to and compensate for quickly enough (Parillo, 2012). At this point, the society must decide if it will adjust by returning to its pre-conflict state or work to find a new equilibrium (Parillo, 2012). Functional theory acts as the opposite of conflict theory because it operates on the premise that humans are inherently cooperative and caring, each playing their role in maintaining the harmony of the society (Schriver, 1998). Functionalists believe that all problems regarding minority groups can be solved by small adjustments in the social system to return to equilibrium (Parillo, 2012). Critics of functionalist theory, who often prefer conflict theory, argue that the focus on stability ignores the inequalities of class, gender, and race that are often the creators of conflict (Parillo, 2012).

In relation to human trafficking and human rights, conflict theory aims to offer a broad explanation for why and how social inequality, power imbalance, and oppression are able to occur. Sexism, racism, and classism are often contributors to human rights violations, as highlighted in the case of child brides, sex trafficking, organ trafficking, and other forms of victimization. Barner, Okech, and Camp (2014) illustrate how socioeconomic inequality not only between classes on a small scale, but globally between developed and underdeveloped nations fuels sex trafficking, violence, and political strife and civil war. From a similar perspective, embracing a functionalist view requires one to question how and why oppression are able to occur. It also requires one to examine the utility of human rights violations and their place in maintaining an equilibrium. For example, functionalists would argue in the past that gender roles existed because they played a functional role in systematically meeting the needs of society with men engaging in labor and wage-earning tasks while women were engaging in homemaking and nurturing tasks (Parillo, 2012). Some would still argue this to be the case in modern times. In the case of human rights, in order to address these kinds of violations, it is important to identify the function the violation plays in maintaining a system within society, and then determining what changes need to be made to move to a new form of harmony absent of the violation. Human trafficking in the form of labor trafficking fulfills the need of cheap labor to create more profits; sex trafficking meets the demand for sex from johns and provides money or other things of value to pimps; child soldiers play various roles in meeting the needs of militant groups during armed conflict; and organ trafficking supplies a limited resource to an ever-growing list of needy recipients. Human rights violations as a whole can always be examined from the perspective of the function they play in a larger picture. In order to prevent human rights violations, however, it is important for social workers and other professionals to understand the need the violation fulfills and intervene at a point that prevents the need for the violation to occur.

Labeling Theory

Labeling theory is a sociological theory based in understanding criminal behavior when a criminal is named as such, and emerged in the 1960s and 1970s from two sociologists named Howard Becker and Edwin Lemert (Crewe & Guyot-Diangone, 2016). This theory sought to untangle the inherent criminality of an individual versus the impact of labels on the criminalization of those deemed deviant (Crewe & Guyot-Diangone, 2016; Restivo & Lanier, 2013). Lemert posited that the act of labeling and creating stigma around what is or can be considered deviant behavior only serves to further marginalize and force conformity to criminal status, as internalizing the label and stigma alters one’s view of self and their social roles (Crewe & Guyot-Diangone, 2016). This further marginalization and conformity is called secondary deviance, which is associated with a shift in self-concept and social expectations, increased association with deviant peers, and an alter in the psychic structure (Crewe & Guyot-Diangone, 2016; Restivo & Lanier, 2013). Labeling theory has also been applied to mental illness, where it is called modified labeling theory. Modified labeling theory is essentially the same as labeling theory, in which the labeling of an individual with a mental illness or as mentally ill often has a negative effect and causes social withdrawal (Crewe & Guyot-Diangone, 2016; Davis, Kurzban & Brekke, 2012).

Some forms of human trafficking, especially sex trafficking, involve criminal activity on the victim’s part, and result in the criminalization of the victim rather than the trafficker (Dempsey, 2015). In these cases, the victim may begin to fit into the traditional model of labeling theory and view themselves as a deviant criminal, thus perpetuating their involvement in trafficking because they believe this is a lifestyle they chose. This is evidenced by some victims having extensive criminal backgrounds, serving time for prostitution and drug charges, and thinking of themselves as willing participants in prostitution and drug trafficking (Meshelemiah & Lynch, 2019), before they are rescued and identified as victims. Hoyle, Bosworth, and Dempsey (2011) highlight the power of the label “victim” in a person’s ability to leave their trafficker, seek supportive services, and move forward with their lives. They also explore the notion of an “ideal” victim through the definitions of trafficking that exist and the images of modern-day slavery that are showcased in the world. In some ways, the creation of a victim label through the media that is available is invalidating to those whose lived experience with trafficking may be seen as complicit or not fit the image of slavery (Hoyle, Bosworth, & Dempsey, 2011). Victims may not believe they are deserving of services unless they were “forced enough”, and see other victims who fit the kidnapped and forced narrative as more deserving of services (Brunovskis & Surtees, 2012, p. 34). Labeling theory exemplifies the power of self-perception as well as the perceptions of law enforcement and service agencies in ensuring victims are correctly identified and receive appropriate services.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is one of the most basic theories of social work and informs much of the field’s practice. Maslow’s hierarchy is designed as a pyramid to showcase the importance of needs being met in order to reach optimal wellness. Psychological and safety needs make up the bottom two tiers, and operate as the components of basic needs (Maslow, 1943). Belongingness and love, and esteem needs are the middle two tiers as well as the components for psychological needs (Maslow, 1943). Then, finally, self-actualization tops the pyramid as the component for self-fulfillment needs (Maslow, 1943). In order to reach self-actualization, the most basic of human physical and psychological needs must be met first (Maslow, 1943). If basic needs are not met, like hunger and shelter, the body will focus all efforts on finding these things and the mind will not be able to focus on things of personal interest until basic needs are met (Maslow, 1943). Critics of Maslow’s hierarchy state the model is too simplistic, and fails to account for cultural norms and drives (Gambrel & Cianci, 2003). Additionally, few things in life are linear, and the hierarchy implies a linear route to self-actualization.

In terms of human-trafficking, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs can help practitioners understand why victims are drawn to and controlled by traffickers. As highlighted in other chapters, risk factors for victims include homelessness, prior neglect and abuse, and poverty. A lack of housing, food, clothing, safety, and financial security cover most of the two rungs of basic needs in Maslow’s hierarchy. Traffickers are able to offer these things to victims, which both draws victims to traffickers as well as makes it difficult to leave (Hopper, 2016; Hopper & Hidalgo, 2006; Stotts & Ramey, 2009). Traffickers also offer intimate relationships and friendships, even if temporarily, meeting some aspects of psychological needs and further bonding victims to them–this is especially true in the case of sex trafficking of minors (Reed, Kennedy, Decker, & Cimino, 2019; Smith, Vardaman, & Snow, 2009). In addressing the recovery and healing of human trafficking victims, service providers must work up the pyramid to be effective; first addressing basic needs like housing, clothing, food, and a sense of security and safety from their trafficker (Gezinski & Karandikar, 2013; Hopper, 2016). Once basic needs have been met, psychological needs can be addressed through group settings, therapeutic interventions, trauma therapy, and a sense of accomplishment in healing. Then survivors, following Maslow’s hierarchy, will be on track to reach self-actualization. See Maslow’s diagram in Figure B.

Figure B. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

The theories covered in this chapter are in no way an exhaustive list of the only theories that can be applied to human trafficking and human rights violations. They are, however, some of the most common theories used in understanding these topics. In many cases, the theoretical approach is not explicitly outlined, or is assumed because of the field of focus. However, it is easy to see how some of these theories are applicable in a variety of contexts when understanding human trafficking and human rights.

Quiz

Now, let’s shift gears and turn to a “thought” on theories.

THEORY AND HUMAN TRAFFICKING

Using a theoretical framework in academic research, intervention development, and policy-making takes out some of the guessing work about efficacy and risk of failure. Theories are empirically-based and developed on a set of consistent assumptions that set the context and background for existing knowledge. For example, theories about human development and needs can set the groundwork for studies on understanding behavior within a certain stage of development, with or without certain needs being met, or when adverse experiences occur during a stage. Using theory allows researchers to get directly to the questions they need answered without having to do multiple studies to set a background and context. For intervention development and policy-making, theory gives a set of basic assumptions about societal and individual contexts that the interventions and policies must exist and work within.

In relation to human trafficking and human rights work, using theory allows us to have a context for how and why injustice occurs. It provides a basic understanding of the needs of those whose rights have been violated. It allows us to predict how effective interventions and policies will be based on how they fit into the assumptions of the chosen theoretical foundation. Applying theory to understanding human rights is important because it ensures that scholars, activists, policymakers, and more are functioning under the same umbrella of understanding about the extant knowledge, context, and basic assumptions of a phenomenon; this allows us to work toward the same goal through unique disciplinary and interdisciplinary lenses without working backward in re-studying the same foundations. Theory allows human rights advocacy to continually move forward.

Summary of Key Points

- The social work profession utilizes theories from a variety of fields. Some cover basic human development while some are more complex and can explain criminal and deviant behavior.

- Utilizing theories that explore power, control, development, and deviant behavior can help social workers and other professionals to develop impactful interventions informed by theory and years of research on the topic.

Supplemental Learning Materials

Lutya, T.M. & Lanier, M. (2012). Chapter 27: An integrated theoretical framework to describe human trafficking of young women and girls for involuntary prostitution. In J. Maddok (Ed.). Public Health – Social and Behavioral Health. (555-570). DOI: 10.5772/37064

References

Berg-Weger, M. (2005). Social Work & Social Welfare: An Invitation. McGraw-Hill. New York, NY.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1994). Ecological models of human development. International Encyclopedia of Education, Vol. 3, 2nd. Ed. Oxford: Elsevier. Retrieved from http://edfa2402resources.yolasite.com/resources/Ecological%20Models%20of%20Human%20Development.pdf

Brunovskis, A., & Surtees, R. (2012). Leaving the past behind? When victims of trafficking decline assistance: Summary report. Fafo AIS (OSLO) & Nexus Institute. Retrieved from https://www.digiblioteket.no/files/get/McxE/20258.pdf

Clawson, H. Small, K., Go, E., & Myles, B. (2003). Needs Assessment for Service Providers and Trafficking Victims. Caliber Associates, Inc. Retrieved from https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/202469.pdf

Crewe, S.E., & Guyot-Diangone, J. (2016). Stigmatization and labeling. Encyclopedia of Social Work. DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780199975839.013.1043

Davis, L., Kurzban, S., & Brekke, J. (2012). Self-esteem as a mediator of the relationship between role functioning and symptoms for individuals with severe mental illness: A prospective analysis of modified labeling theory. Schizophrenia Research, 37(1), 185-189. DOI: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.02.003

Dempsey, M. M. (2015). Decriminalizing victims of sex trafficking. American Criminal Law Review, 52(2), 207-230. Retrieved from https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/amcrimlr52&i=227

Forder, A. (1976). Social work and system theory. The British Journal of Social Work, 6(1), 23-42. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjsw.a056695

Gambrel, P. & Cianci, R. (2003). Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs: Does it apply in a collectivist culture. Journal of Applied Management and Entrepreneurship, 8(2), 143-156. Retrieved from http://proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/docview/203916225?accountid=9783.

Gezinski, L.B. & Karandikar, S. (2013). Exploring needs of sex workers from Kamathipura red-light area of Mumbai, India. Journal of Social Service Research, 39(4), 552-561. DOI: 10.1080/01488376.2013.794758

Hopper, E. (2016). Trauma-informed psychological assessment of human trafficking survivors. Women & Therapy, 40(1-2), 12-30. DOI: 10.1080/02703149.2016.1205905

Hoyle, C., Bosworth, M., & Dempsey, M. (2011). Labeling the victims of sex trafficking: Exploring the borderland between rhetoric and reality. Social & Legal Studies, 20(3), 313-329. DOI: 10.1177/0964663911405394

Hutchison, E. (2013). Social work education: Human behavior and social environment. Encyclopedia of Social Work. DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780199975839.013.616Kondrat, M. E. (2013). Person-in-environment. Encyclopedia of Social Work. DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780199975839.013.285

Leighninger, R. (1977). Systems theory and social work: A reexamination. Journal of Education for Social Work, 13(3), 44-49. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/stable/23038730

Maslow, A. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370-396. Retrieved from http://www.researchhistory.org/2012/06/16/maslows-hierarchy-of-needs/

Meshelemiah, J. & Lynch, R. (2019). Sex Trafficking: The Intersection of Race, Drugs, “Dope Boys” – and Emergent Leaders. (Presentation). The Kirwan Institute, Columbus, OH.

Parillo, V. (2012). Strangers to these Shores (10th Ed.). Pearson Education, Inc. Boston, Mass.

Reed, S., Kennedy, M., Decker, M., & Cimino, A. (2019). Friends, family, and boyfriends: An analysis of relationship pathways into commercial sexual exploitation. Child Abuse & Neglect, 90, pg 1-12. DOI: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.01.016

Restivo, E., & Lanier, M. (2013). Measuring the contextual effects and mitigating factors of labeling theory. Justice Quarterly. DOI: 10.1080/07418825.2012.756115

Rӧssel, J. (2013). Conflict theory. Oxford Bibliographies in Sociology. DOI: 10.1093/OBO/9780199756384-0035

Sallis, J. F., & Owen, N. (2015). Chapter 3: Ecological models of health behavior. In K. Glanz, B. K. Rimer, & K. Viswanath (Eds.), Health behavior: Theory, research, and practice (5th ed.) (pp. 43-65). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Shriver, J. (1998). Human Behavior and the Social Environment: Shifting Paradigms in Essential Knowledge for Social Work Practice (2nd Ed.). Allyn & Bacon. Needham Heights, Mass.Skyttner, L. (1996). General Systems Theory: Origin and hallmarks. Kybernetes, 25(6), 16-22. DOI: 10.1108/03684929610126283

Smith, L., Vardaman, S., & Snow, M. (2009). The National Report on Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking America’s Prostituted Children. Shared Hope International. Retrieved from http://sharedhope.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/SHI_National_Report_on_DMST_2009.pdf

Stotts, E., & Ramey, L. (2009). Human trafficking: A call for counselor awareness and training. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education and Development, 48(Spring), 36-47. DOI: 10.1002/j.2161-1939.2009.tb00066.x