Chapter 1: Social Work, Social Justice, Human Rights and Human Trafficking

ABSTRACT

Trafficking in Persons, which is commonly known as human trafficking, is a human rights issue that is grossly misunderstood and mostly undetected. It is a criminal enterprise that is estimated to impact millions of individuals and families around the world. The lack of identification of victims by victims, law enforcement, the general public and service providers plays a major role in the clandestine nature of human trafficking. Social workers, however, must take on a more proactive role in addressing human trafficking.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, the student will be able to:

- Understand social work as a profession

- Define trafficking in persons as stipulated by the United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, Supplementing the United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime

- Define human rights in accordance with the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR)

Key Words: Social Work, Social Justice, Trafficking in Persons, Human Rights

GLOSSARY

Social Work: A profession that is charged with promoting social justice and preserving human rights; persons who work under the umbrella of social work are called social workers. They are licensed/certified persons with college degrees from accredited institutions of higher learning—primarily from units that offer social work programs

Social Justice: The view that everyone deserves equal economic, political and social rights and opportunities

Trafficking in Persons: Shall mean the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or of receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation

Human Rights: Basic rights and freedoms that all people are entitled to regardless of nationality, sex, national or ethnic origin, race, religion, language or other status

Social Work, Social Justice, Human Rights and Human Trafficking

Social work began over 100 years ago with Mary Richmond, who founded the Charity Organization Society (COS), and Jane Addams, who founded the settlement house movement (Lesser & Pope, 2007; Tannenbaum & Reisch, 2001). Specifically, COS came into existence in 1877 in Buffalo, New York, under the leadership of Mary Richmond (COS) while Jane Addams opened the Hull House in Chicago, Illinois, in 1889. The COS was responsible for sending out “friendly visitors” to European immigrant communities to help them assimilate into American culture. They were the profession’s first case managers. Mary Richmond also established the first school of social work at Columbia in 1898 (Segal, Gerdes, & Steiner, 2013). Jane Addams, on the contrary, felt strongly that it was important to live among the people she was to serve. As a result, she founded the Hull House, where social services could be delivered right in the heart of the community where clients lived. She was an innovative agent of change and an activist who was unwavering in her pursuit of justice (civil, social, political, legal, and economic) and empowerment of all (Addams, 1959; Gil, 2013; Meshelemiah, 2016, in Press).

Despite their opposing approaches to social justice as founders of social work, both Jane Addams and Mary Richmond sought to serve vulnerable groups of people. Unlike Mary Richmond, however, Jane Addams embraced social action and macro approaches to advocacy by speaking out against World War I, environmental injustices (i.e., garbage removal in poor communities), child workers, the lack of a juvenile justice system, women’s right to vote, adult education, and the inhumane treatment of immigrants (Addams, 1959; Segal, Gerdes, & Steiner, 2013). Despite Jane Addams’ legacy of confronting people and systems that oppress and marginalize vulnerable groups of people, the profession of social work in the 21st century is still not at the forefront of explicitly articulating its stance on human rights (Healy, 2008, 2015). This includes the profession’s lack of involvement in anti-trafficking activities. Human trafficking is a widespread form of modern-day enslavement that strips victims of their human rights on a daily basis. It is a form of human profiteering (Alvarez & Alessi, 2012) that captured the attention of the United Nations and the United States in 2000 through its seminal pieces of legislation.

Severe Human Trafficking is a term that was officially coined and adopted in 2000 through the enactment of the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act (VTVPA). This Act is best known for its subsection on human trafficking, which is known as the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA). Human trafficking activities are primarily categorized as Sex trafficking or Labor trafficking. Sex trafficking involves the elements: force, fraud or coercion. These means are used to induce others into commercial sex activities. Force, fraud or coercion are not necessary elements for those less than 18 years of age given their minor status. Labor trafficking, through the use of force, fraud and coercion, involves making a person provide labor services for free; for far less than what was agreed upon; or under terms that were not agreed upon prior to employment (Okech, Morreau, & Benson, 2011; Meshelemiah, in Press, Pub. L. 106-386). It presents in the form of debt bondage, peonage, indentured servitude or slavery (Pub. L. 106-386). The most comprehensive definition of trafficking, however, is the one adopted by the UN Office of Drugs and Crime in 2000, which is known as the United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, Supplementing the United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime (United Nations, 2000, p.3):

Article 3 of the said Protocol reads as follows:

- a) Trafficking in persons shall mean the recruitment, transportation, transfer, habouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or of receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs;

- b) The consent of a victim of trafficking in persons to the intended exploitation set forth in sub paragraph (a) of this article shall be irrelevant where any of the means set forth in sub paragraph (a) have been used;

- c) The recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of a child for the purpose of exploitation shall be considered ‘trafficking in persons’ even if this does not involve any of the means set forth in sub paragraph (a) of the article;

- d) ‘Child’ shall mean any person under eighteen years of age.

Prevalence

Due to the clandestine nature of human trafficking, researchers rely on estimates and proxies when determining the prevalence of human trafficking. The International Labor Organization (2014) espouses that there are at least 12.3 million people who are enslaved in some form worldwide– more than at any time in history. The Global Slavery Index estimates it to be over 40 million (Global Slavery Index, 2018). While there is no official estimate of the total number of persons who are human trafficked in the United States, Polaris estimates that the actual number of victims in the U.S. reaches into the hundreds of thousands when estimates of sex and labor trafficking are aggregated for adults and minors (Polaris, 2017). Since 2007, Polaris has received 156,312 calls related to suspected human trafficking activities, 11,601 web form completions, and 11,058 emails. Of this number, 43,564 were rated as a high indicator for severe human trafficking while 45,241 were rated as a moderate indicator for severe human trafficking. Those with a moderate indicator lacked details related to force, fraud and/or coercion (Polaris, 2017). Although not exactly precise in numbers, Polaris statistics serve as frequently quoted proxies for the prevalence of human trafficking in the United States.

The United States falls 134th out of 162 nations ranked for their trafficking estimates (Walk Free Foundation, 2013). Although the U.S.’s count of human trafficked persons is based on the legal definition as espoused by the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA), the most frequently cited definition of trafficking is the one adopted by the UN Office of Drugs and Crime (UN, 2000; Zimmerman & Stockl, 2012). As previously stated, this document is known as the United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, Supplementing the United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime (United Nations, 2000). The United States is a member state of the United Nations (United Nations, 2014) and is a signatory on this protocol (Hendrix, 2010). On a domestic level, the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) of 2000 defines sex trafficking as commercial sex activities (CSA) that include forced prostitution in brothels, private homes, dancing bars, strip clubs, and massage parlors, for instance. It also includes pornography (Meshelemiah & Sarkar, 2015; Public Law No. 106-386).

Regardless of which definition that one subscribes to, enslaving others is situated as wrong and illegal by all governments around the world. Slavery, modern day slavery, trafficking in persons, and human trafficking are all interchangeable terms and refer to the same phenomenon. It is estimated that 14,500 – 17,500 foreign nationals are trafficked into the United States annually (Fedina, Trease, & Williamson, 2008) as there is a high demand for “exotic” women in the United States (Robertson, 2012). Other researchers estimate the number at a much higher rate by asserting that 45,000 – 50,000 persons are trafficked into the U.S. annually (George, 2012; Miko & Park, 2001). Most trafficked persons in the U.S. come from South East Asia and South Asia, followed by Central/Eastern Europe, Latin America, the Caribbean and Africa (Miko & Park, 2001; Okech, Morreau, & Benson, 2011). Since the inception of the TVPA, the focus of the anti-trafficking legal discourse in the United States has been primarily on foreign victims who are sex trafficked into the country (Public Law 106-386). This focus on foreign national victims appears to be mainly the result of the fact that 83% of alleged human trafficking incidents in the United States involve sex trafficking allegations and nearly half of them are foreign nationals (Polaris, 2017; Sager, 2012). According to Polaris (2017), of the 8,524 cases reported in 2017, 7,067 involved women and girls; 5,278 involved adults. Of the 3,457 identified by nationality, 1,947 were identified as US citizens while 1,510 were identified as foreign nationals.

Intersection Between Human Rights and Human Trafficking

Almost 30 years ago, the International Federation of Social Workers (IFSW) declared social work to be a human rights profession (IFSW, 1988). Despite this proclamation, most social workers do not identify as human rights champions although social workers are inculcated with a value system that believes in promoting social justice given that the NASW Code of Ethics espouses that social workers must promote social justice (Healy, 2015; NASW, 1996, 2017). “Social justice is the view that everyone deserves equal economic, political and social rights and opportunities” (NASW, 2017a, paragraph 2) while human rights are broadly defined as the “basic rights and freedoms that all people are entitled to regardless of nationality, sex, national or ethnic origin, race, religion, language or other status” (Amnesty International USA, 2015, Human Rights section). Specifically, social workers believe that all humans deserve to be treated with dignity and worth and afforded access to basic necessities as role modeled by our Founding Mothers. The social justice lens is quite apparent in the social work profession (Lesser & Pope, 2007; Segal, Gerdes, & Steiner, 2013). Somewhere along the way, however, social workers as a whole have failed to move along the spectrum of justice and evolve into agents who adopted the responsibility to understand and protect human rights. Transitioning to brokers of human rights has been slow in coming (Healy, 2008, 2015; Reichert, 2001). As a profession, social workers tend to focus on the needs of clients in pursuit of social justice instead of the rights of clients (Reichert, 2011). Social work as a profession must move to the next level of intervention and advocacy.

Human Rights Articles

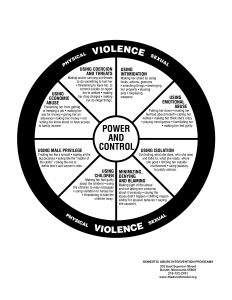

Many people do not recognize human trafficking as modern-day slavery, nor as a human rights issue. The authors argue that human trafficking must be understood as a human rights issue and approached accordingly in all policies and practices. This includes viewing access to social services as a human rights issue. Specifically, Article 25 of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) states that, “everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services…” (United Nations, 1948, Article 25). The United Nations UDHR articles speak directly to living with basic necessities and accessing needed social services as a human right. When a person is under the power of control of another as shown in Figure A [the Power and Control Wheel], however, she or he is deprived of her or his human rights.

Figure A. Power and Control Wheel

In 1948, the United Nations painstakingly established the unarguable rights that every human is innately entitled to at birth through its 30 Articles in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) (United Nations, 1948). The signatories of this document (including the United States) intended to promote and commit to a mutual respect and recognition of dignity of all people. Many of the 30 Articles within the UDHR either directly or indirectly denounce and/or address the ramifications of slavery in its numerous forms, but two are arguably the most explicit: Article 4 states that, “no one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms” (United Nations, 1948, Article 4); and Article 23 states that, “everyone has the right to work, to free choice of employment, to just and favorable conditions of work…” (United Nations, 1948, Article 23). Modern-day slavery is clearly in violation of these two UDHRs. Pescinski (2015) asserts that a human rights approach to trafficking demands that the rights of trafficking victims serve as the impetus for all policies designed to benefit them. Okogbule (2013) concurs and states that human trafficking is a gross violation of human rights. He asserts that a human rights framework is an important legal mechanism for combating human trafficking.

The UN issued the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) in 1948. The UN did this in an attempt to bring attention to the inalienable rights of all people (United Nations, 1948). The UDHR contains 30 Articles. These articles address civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights (United Nations, 1948, Articles 1-30). As seen in Figure B, Article 1 of the UDHR states that all humans are equal in dignity and worth. Articles 2–15 address political and individual freedoms. Articles 16–27 address economic, social, and cultural rights. Articles 28 and 29 address collective rights among and between nations and Article 30 states that no one can take away a person’s human rights (United Nations, 1948). See Figure B for a summary of the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The complete wording of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights can be found at the end of this chapter.

Figure B. Universal Declaration of Human Rights Summary

Recommendations

Social work practice, by virtue of its mission and charge, aligns closely with the promotion of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Whether consciously recognized or not, social workers work daily to ensure and provide access to basic needs like food, housing, education, healthcare, and employment for the people they work with and work for. These service provisions are consistent with the promotion of human rights as stated in Articles 23 and 25 of the UDHR (Riches, 2002; United Nations, 1948). Despite these service provisions by social workers, it appears that social work students and practitioners view these activities as “helping” people, being a “do-gooder” or “just doing my job”. In reality, however, providing access to basic necessities to people exceeds helping. These activities are in direct accordance to imperatives of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It is time that social work educators start to emphasize the language around human rights by using it so frequently that “human rights” as a term becomes official nomenclature of the profession.

Education

The Council on Social Work Education (CSWE) accredits undergraduate and graduate social work programs throughout the United States and its territories. Accreditation of these institutions is based on CSWE’s Educational Policy and Accreditation Standards (EPAS). All accredited programs must adhere to these standards. The explicit curriculum requires programs to integrate a human rights perspective (as a component of its nine competency-based requirements). The adoption of this component must be evident in an institution’s social work education (competency-based education) and the field practicum (field education) (CSWE, 2015; Meshelemiah, 2016). Students, educators, field education supervisors and practitioners must pay full attention to this language and buy into it as a part of their professional responsibilities.

CSWE requires that students work to Advance Human Rights and Social, Economic, and Environmental Justice.

Specifically, Competency 3 of the EPAS states that:

Social workers understand that every person regardless of position in society, has fundamental human rights such as freedom, safety, privacy, an adequate standard of living, healthcare, and education. Social workers understand the global connections of oppression and human rights violations, and are knowledgeable about theories of human need and social justice and strategies to promote social and economic justice and human rights. Social workers understand strategies designed to eliminate oppressive structural barriers to ensure that social goods, rights, and responsibilities are distributed equitably and that civil, political, environmental, economic, social, and cultural human rights are protected. Social workers apply their understanding of social, economic, and environmental justice to advocate for human rights at the individual and system levels; and engage in practices that advance social, economic, and environmental justice (CSWE, 2015, pp. 7–8).

The charge around human rights and social work is clear. It is time that social work’s paradigm reflects this directive. This text, The Cause and Consequence of Human Trafficking: Human Rights Violations, is intended to convey the importance of understanding how the violation of human rights is a cause and consequence of human trafficking. In other words, human rights violations are egregious and they compound destitution. They deprive the man, woman and child of their basic humanity. Whenever any dimension of one’s humanity is deprived, it puts the person in a compromised state. Compromised states lead to some degree of impairment, distress or suffering. Impairment, distress or suffering leads to a disequilibrium in a person’s life. In an effort to quiet that compromised state, the individual may unknowingly make decisions that further compromise her or his state of being or result in human trafficking. These compromises can present in the form of an impoverished Sri Lankan husband who is denied the right to work so he takes out a predatory loan that leads to debt bondage. It could be an ostracized young widow from Ethiopia with no safety net who takes a domestic job abroad that leads to indentured servitude. It could be the Romanian bride who is refused work due to her nationality so she decides to marry a foreigner abroad for love but is forced into selling her body instead. It could be the homeless Ugandan teenager who cannot pay school fees to attend school so he decides to join the army as a cook, but is forced to serve as a murderous child soldier instead; or it could be the Indian from a lower caste that cleans the sewage without a uniform or even gloves that decides to sell his kidney for a large amount of money but only ends up gravely ill and receiving only a fraction of the promised amount. In all of these scenarios, the person began in a compromised state due to human rights violations, became ensnared in some form of trafficking and then was subjected to further violations of human rights. This is how human rights deprivations work—they are full of consequences.

Quiz

Now, let’s shift gears and turn to a case study.

KIM

Much of her childhood was spent in poverty, and when she thinks of her life then, she says, “We were really poor. We could barely make ends meet. We needed money for my siblings’ education.” Kim was 12 years old and vulnerable to the lies of criminals whose only aim was to prey on and exploit her. Criminals like AJ. AJ was Kim’s neighbor, and he promised to put her in school if she moved with him to Manila. He even promised her a job to help her siblings pay their school fees. Never in their worst dreams did Kim’s parents think AJ would hurt her, so they allowed her to go with him. At first, nothing seemed wrong. In fact, Kim had a more comfortable life than she had ever experienced. AJ sent her to a good school and treated her well. But that was all about to change. A few months after Kim arrived at AJ’s home, he took a photo of her. A nude photo. Kim’s exploitation had begun. What started out as a nude photo turned into posing naked in front of a webcam, as well as sexual abuse by AJ himself. These horrific images were then streamed over the internet to pedophiles and predators across the world. This is cybersex trafficking. Kim endured this unimaginable pain for three years. She recalls the abuse and her fear of AJ, saying, “It was like he had a total grasp on me and it was so difficult to break away.” The abuse of Kim didn’t stop with online exploitation. One night, AJ brought Kim to a hotel, thinking it would be another night of selling Kim’s body to a stranger. Kim was also expecting another night of abuse, but when the hotel room door opened, she saw the faces of law enforcement officers. She was afraid she was going to be arrested, but IJM social workers on the scene were able to reassure Kim that she wasn’t in trouble. She was free, and AJ was the one being arrested.

(International Justice Mission [IJM], 2019 Case Study-verbatim account)

As shown in the case of Kim, trafficking can and sometimes does involve trusted neighbors pretending to care about the economics of one’s family only to have malevolent intentions from the onset. Fortunately for Kim, AJ was arrested for his trafficking crimes—but not before he subjected her to three years of cybersex trafficking and sexual abuse.

Summary of Key Points

- Social workers are charged with promoting social justice.

- Social workers are charged with preserving human rights.

Supplemental Learning Material

Table 1. Universal Declaration of Human Rights

United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is a milestone document in the history of human rights. Drafted by representatives with different legal and cultural backgrounds from all regions of the world, the Declaration was proclaimed by the United Nations General Assembly in Paris on 10 December 1948 (General Assembly resolution 217 A) as a common standard of achievements for all peoples and all nations. It sets out, for the first time, fundamental human rights to be universally protected and it has been translated into over 500 languages.

Preamble

Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world,

Whereas disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind, and the advent of a world in which human beings shall enjoy freedom of speech and belief and freedom from fear and want has been proclaimed as the highest aspiration of the common people,

Whereas it is essential, if man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression, that human rights should be protected by the rule of law,

Whereas it is essential to promote the development of friendly relations between nations,

Whereas the peoples of the United Nations have in the Charter reaffirmed their faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person and in the equal rights of men and women and have determined to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom,

Whereas Member States have pledged themselves to achieve, in co-operation with the United Nations, the promotion of universal respect for and observance of human rights and fundamental freedoms,

Whereas a common understanding of these rights and freedoms is of the greatest importance for the full realization of this pledge,

Now, Therefore THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY proclaims THIS UNIVERSAL DECLARATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS as a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations, to the end that every individual and every organ of society, keeping this Declaration constantly in mind, shall strive by teaching and education to promote respect for these rights and freedoms and by progressive measures, national and international, to secure their universal and effective recognition and observance, both among the peoples of Member States themselves and among the peoples of territories under their jurisdiction.

Article 1.

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Article 2.

Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty.

Article 3.

Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person.

Article 4.

No one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms.

Article 5.

No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

Article 6.

Everyone has the right to recognition everywhere as a person before the law.

Article 7.

All are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimination to equal protection of the law. All are entitled to equal protection against any discrimination in violation of this Declaration and against any incitement to such discrimination.

Article 8.

Everyone has the right to an effective remedy by the competent national tribunals for acts violating the fundamental rights granted him by the constitution or by law.

Article 9.

No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest, detention or exile.

Article 10.

Everyone is entitled in full equality to a fair and public hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal, in the determination of his rights and obligations and of any criminal charge against him.

Article 11.

(1) Everyone charged with a penal offence has the right to be presumed innocent until proved guilty according to law in a public trial at which he has had all the guarantees necessary for his defence.

(2) No one shall be held guilty of any penal offence on account of any act or omission which did not constitute a penal offence, under national or international law, at the time when it was committed. Nor shall a heavier penalty be imposed than the one that was applicable at the time the penal offence was committed.

Article 12.

No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.

Article 13.

(1) Everyone has the right to freedom of movement and residence within the borders of each state.

(2) Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country.

Article 14.

(1) Everyone has the right to seek and to enjoy in other countries asylum from persecution.

(2) This right may not be invoked in the case of prosecutions genuinely arising from non-political crimes or from acts contrary to the purposes and principles of the United Nations.

Article 15.

(1) Everyone has the right to a nationality.

(2) No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his nationality nor denied the right to change his nationality.

Article 16.

(1) Men and women of full age, without any limitation due to race, nationality or religion, have the right to marry and to found a family. They are entitled to equal rights as to marriage, during marriage and at its dissolution.

(2) Marriage shall be entered into only with the free and full consent of the intending spouses.

(3) The family is the natural and fundamental group unit of society and is entitled to protection by society and the State.

Article 17.

(1) Everyone has the right to own property alone as well as in association with others.

(2) No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his property.

Article 18.

Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.

Article 19.

Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.

Article 20.

(1) Everyone has the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and association.

(2) No one may be compelled to belong to an association.

Article 21.

(1) Everyone has the right to take part in the government of his country, directly or through freely chosen representatives.

(2) Everyone has the right of equal access to public service in his country.

(3) The will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of government; this will shall be expressed in periodic and genuine elections which shall be by universal and equal suffrage and shall be held by secret vote or by equivalent free voting procedures.

Article 22.

Everyone, as a member of society, has the right to social security and is entitled to realization, through national effort and international co-operation and in accordance with the organization and resources of each State, of the economic, social and cultural rights indispensable for his dignity and the free development of his personality.

Article 23.

(1) Everyone has the right to work, to free choice of employment, to just and favourable conditions of work and to protection against unemployment.

(2) Everyone, without any discrimination, has the right to equal pay for equal work.

(3) Everyone who works has the right to just and favourable remuneration ensuring for himself and his family an existence worthy of human dignity, and supplemented, if necessary, by other means of social protection.

(4) Everyone has the right to form and to join trade unions for the protection of his interests.

Article 24.

Everyone has the right to rest and leisure, including reasonable limitation of working hours and periodic holidays with pay.

Article 25.

(1) Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control.

(2) Motherhood and childhood are entitled to special care and assistance. All children, whether born in or out of wedlock, shall enjoy the same social protection.

Article 26.

(1) Everyone has the right to education. Education shall be free, at least in the elementary and fundamental stages. Elementary education shall be compulsory. Technical and professional education shall be made generally available and higher education shall be equally accessible to all on the basis of merit.

(2) Education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and to the strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. It shall promote understanding, tolerance and friendship among all nations, racial or religious groups, and shall further the activities of the United Nations for the maintenance of peace.

(3) Parents have a prior right to choose the kind of education that shall be given to their children.

Article 27.

(1) Everyone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits.

(2) Everyone has the right to the protection of the moral and material interests resulting from any scientific, literary or artistic production of which he is the author.

Article 28.

Everyone is entitled to a social and international order in which the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration can be fully realized.

Article 29.

(1) Everyone has duties to the community in which alone the free and full development of his personality is possible.

(2) In the exercise of his rights and freedoms, everyone shall be subject only to such limitations as are determined by law solely for the purpose of securing due recognition and respect for the rights and freedoms of others and of meeting the just requirements of morality, public order and the general welfare in a democratic society.

(3) These rights and freedoms may in no case be exercised contrary to the purposes and principles of the United Nations.

Article 30.

Nothing in this Declaration may be interpreted as implying for any State, group or person any right to engage in any activity or to perform any act aimed at the destruction of any of the rights and freedoms set forth herein.

United Nations. (1948). United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights. New York: Author.

References

Addams, J. (1959). Twenty years at Hull-House. New York: Macmillan Company.

Alvarez, M.B., & Alessi, E.J. (2012). Human trafficking is more than sex trafficking and prostitution: Implications for social work. Affilia: Journal of Women and Social Work, 27(2), 142-152.

Amnesty International USA. (2015). Human rights basic. Retrieved from, www.amnestyusa.org/research/human-rights-basics

Council on Social Work Education. (2015). Educational policy and accreditation standards for baccalaureate and master’s social work programs. Alexandria, VA: Author.

Fedina, L., Trease, J., & Williamson, C. (2008). Human trafficking in Ohio: A resource guide for social service providers. Toledo, Ohio: Second Chance.

George, S. (2012). The strong arm of the law is weak: How the Trafficking Victims Protection Act fails to assist effectively victims of the sex trade. Creighton Law Review, 45, 563-580.

Gil, D.G. (2013). Confronting injustice and oppression: Concepts and strategies for social workers. New York: Columbia University Press.

Global Slavery Index. (2018). Retrieved from https://downloads.globalslaveryindex.org/ephemeral/GSI-2018_FNL_180907_Digital-small-p-1561124710.pdf

Healy, L. (2008). Exploring the history of social work as a human rights profession. International Social Work, 51(6), 735-748.

Healy, L. (2015). Exploring the history of social work as a human rights profession. International Federation of Social Workers. Retrieved from http://ifsw.org/publications/human rights/the-centrality-of-human-rights-to-social-work/exploring-the-history-of-social-work-as-a-human-rights-profession/

Hendrix, M.C. (2010). Enforcing the US Trafficking Victims Protection Act in emerging markets: The challenge of affecting change in India and China. Cornell International Law Journal, 43(1), 173-205.

International Federation of Social Workers (IFSW). (1988). Standards in Social Work Practice meeting Human Rights: Executive Summary. Berlin. Germany: Author.

International Justice Mission. (2019). Nothing seemed wrong at first. But everything was about to change. Retrieved from https://www.ijm.org/stories/kim

International Labor Organization. (2014). labour, human trafficking and slavery. Retrieved from http://www.ilo.org/global/topics/-labour/lang–en/index.htm

Karger, H. (2015). Curbing the financial exploitation of the poor: Financial literacy and social work education. Journal of Social Work Education, 51(3), 425-438.

Lesser, J.G., & Pope, D.S. (2007). Human behavior and the social environment: Theory and practice. Boston: Pearson/Allyn & Bacon.

Meshelemiah, J.C.A. (In Press). Training social workers in anti-trafficking service. International Handbook on Human Trafficking: An Interdisciplinary and Applied Approach. Routledge/Taylor & Francis.

Meshelemiah, J.C.A. (2016). Human rights perspectives in social work education and practice. Encyclopedia of Social Work. Washington, DC: National Association of Social Workers Press/Oxford University Press.

Meshelemiah, J.C.A. & Sarkar, S. (2015). A comparative study of child trafficking in India and the United States. Journal of Trafficking: Organized Crime and Security, 1(2), 126-137.

Miko, F. T., & Park, G. (2001). Trafficking in women and children: The U.S. and international response – Updated August 1, 2001. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service.

National Association of Social Workers. (1996). NASW Code of Ethics. Washington DC: Author.

National Association of Social Workers. (2017). Social justice. Retrieved from, http://www.socialworkers.org/pressroom/features/Issue/peace.asp

Okech, D., Morreau, W., & Benson, K. (2011). Human trafficking: Improving victim identification and service provision. International Social Work, 55(4), 488-503.

Okogbule, N.S. (2013). Combating the “new slavery” in Nigeria: An appraisal of legal and policy responses to human trafficking. Journal of African Law, 57(1), 57-80.

Pescinski, J. (2015, February 20). A human rights approach to human trafficking. Our World. Retrieved from https://ourworld.unu.edu/en/a-human-rights-approach-to-human-trafficking

Polaris. (2017). Polaris. (2017). Hotline statistics. Retrieved from https://humantraffickinghotline.org/states

Pub. L. 106-386. (2000). Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000, H. R. 3244, (2000). 106th Cong., 2nd Sess.

Reichert, E. (2001). Move from social justice to human rights provides new perspective. Professional Development: International Journal of Continuing Social Work Education, 4(1), 5-13.

Reichert, E. (2011). Social work and human rights: A foundation for policy and practice (2nd ed.). New York: Columbus University Press.

Riches, G. (2002). Food banks and food security: Welfare reform, human rights, and social policy. Lessons from Canada? Social Policy & Administration, 36(6), 648-663.

Robertson, G. (2012). The injustice of sex trafficking and the efficacy of legislation. Global Tides, 6(4). Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/globaltides/vol6/iss1/4

Sager, R.C. (2012). An anomaly of the law: In sufficient state laws fail to protect minor victims of sex trafficking. New England Journal on Criminal & Civil Confinement, 38, 359-378.

Segal, E.A., Gerdes, K.E., & Steiner, S. (2013). An introduction to the profession of social work: Becoming a change agent (4th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson—Brooks/Cole.

Tannenbaum, N., & Reisch, M. (2001). From charitable volunteers to architects of social welfare: A brief history of social work. University of Michigan’s Ongoing Magazine, 7-19.

United Nations. (1948). United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights. New York: Author.

United Nations. (2000). Protocol to prevent, suppress and punish trafficking in persons, especially women and children, supplementing the United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime. New York: Author.

Walk Free Foundation. (2013). Global Slavery Index. Retrieved from, file:///C:/Users/meshelemiah/Downloads/GlobalSlaveryIndex_2013_Download_WEB1.pdf

Zimmerman, C., & Stockl, H. (2012). Understanding and addressing violence against women: Human Trafficking. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (WHO).