Chapter 10: Leadership Among Survivors in the Anti-Trafficking Movement

ABSTRACT

Anti-trafficking efforts tend to be spearheaded by law enforcement agencies at the federal, national, state, and local levels. These agencies are critical macro approaches to eradicating human trafficking. Trafficking survivors, however, are also critical to anti-trafficking efforts at all levels given their experiences as trafficking victims. Proponents of the Survivor Leadership Model advocate for the treatment of trafficking victims, preparation for leadership, and opportunities for trafficking survivors to be leaders.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, the student will be able to:

- Define sex trafficking

- Understand trauma

- Breakdown the Survivor Leadership model

Key Words: Sex Trafficking, Trauma, and Survivor Leadership

GLOSSARY

Sex Trafficking: Involves the recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, or obtaining of a person for the purpose of a commercial sex act (CSA); if the person (foreign national or U.S. citizen) is 18+ years of age, the CSA must be induced by coercion, fraud, or force

Trauma: A deeply distressing or disturbing event that tends to be acute, chronic, or complex

Survivor Leadership: Anti-trafficking efforts that are led by survivors of sex trafficking

Sex Trafficking, Trauma and Survivor Leadership

According to the Office of Victims of Crimes (OVC), it is imperative to engage sex trafficking survivors in anti-human trafficking leadership and decision-making in order to provide effective services to victims (Office of Justice Programs [OJP], 2018). As a result, the OVC continues to find opportunities to engage survivors in the anti-trafficking movement and to support survivor leadership (OJP, 2018). In 2015, the U.S. government enacted the United States Advisory Council on Human Trafficking. This council is made up of eight human trafficking survivors who offer their expertise to various levels of governments, NGOs, scholars, students, activists, survivors, trafficking task forces, and other committed constituent groups (United States Advisory Council on Human Trafficking, 2019). Membership on this council is considered one of the most influential leadership positions that a survivor can hold.

According to the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) of 2000, sex trafficking involves the recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, or obtaining of a person for the purpose of a commercial sex act (CSA). If the person (foreign national or U.S. citizen) is 18+ years of age, the CSA must be induced by coercion, fraud or force (Public Law 106-386). Sex trafficking is widespread in the United States (Kara, 2009). Between 2007 and 2014, 12,508 cases of sex trafficking were reported throughout the United States. In 2014, 90% of the 3,598 cases reported were composed of females (Orme & Ross-Sheriff, 2015). While there is no official estimate of the total number of persons who are human trafficked in the United States, Polaris (a nationally recognized clearinghouse for trafficking information) estimates that the actual number of victims in the U.S. reaches into the hundreds of thousands when estimates of sex and labor trafficking are aggregated for adults and minors. Since 2007, Polaris has received 156,312 calls related to suspected human trafficking activities, 11,601 web form completions, and 11,058 emails (Polaris, 2017). Although not exactly precise in numbers, Polaris statistics serve as frequently quoted proxies for the prevalence of human trafficking in the United States.

Many sex trafficked victims suffer from depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, dissociative disorders, borderline personality disorder, eating disorders, substance disorders, and suicide attempts (Farley, 2010; Raymond & Hughes, 2001; Sigmon, 2008; Williamson, Dutch & Clawson, 2007). According to the most current version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) of Mental Disorders, trafficking victims are especially at high risk for developing Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). Trauma is considered to be a combination of the event, the experience, and the effect (SAMHSA, 2014). Consistent with the previously stated disorders, Raymond and Hughes (2001) report that many survivors report numbness, depression, lethargy, self-blame/guilt, poor concentration, loss of appetite, and sleep disturbances. The American Psychiatric Association shows that trauma is oftentimes co-morbid with substance misuse and other DSM disorders (APA, 2013). As a result, many of these women seek out social services at some point in their lives (Williamson, Dutch & Clawson, 2007). It is during these times of formal social service interventions that many sex trafficked women learn empowerment strategies, gain their independence, come to identify as victims for the first time, and then move onto identifying as survivors. Some then move on and learn how to be leaders in the anti-trafficking movement (Lloyd, 2008).

Despite the tragic ordeals of trafficked persons, a Survivor Leadership model does not consider sex trafficking victims as victims—it views them as survivors given that the person has survived a horrible injustice. The word “victim” is a legal term, which suggests that the person has experienced criminal harm, whereas the word “survivor” emphasizes that the person is strong and can recover (Office for Victims and Crimes—Training and Technical Assistance Center, 2018). During and after recovery, many survivors go on to become leaders. Survivors need the same skills to fulfill leadership roles as anyone else but their trainings tend to be situated in a clinical context instead.

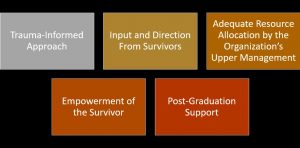

A Survivor Leadership model has five main components as shown in Figure 1. It recognizes the need for multilateral services for trafficking victims with the intent to heal her, empower her, and provide her with a skill set that prepares her to be a leader in the anti-trafficking arena as an expert. The model acknowledges the trauma in the life of the trafficked person and the need to approach victims in a trauma-informed manner. It calls for soliciting the expertise of the survivor in service delivery. It demands adequate resources to deliver services. It moves the victim to a state of being a survivor through empowerment services and it calls for continued support of the survivor post treatment (Family and Youth Services Bureau, 2015).

Figure 1. Survivor Leadership Model

Components of a Survivor Leadership Model

Trauma-informed approach. A trauma informed approach recognizes “that survivors need to be respected, informed, connected, and hopeful regarding their own recovery; the interrelation between trauma and symptoms of trauma such as substance abuse, eating disorders, depression, and anxiety; and the need to work in a collaborative way with survivors, family and friends of the survivor, and other human services agencies in a manner that will empower survivors…” (SAMHSA, 2018, “Trauma-Specific Interventions” section). The five guiding principles of trauma informed care include ensuring safety; giving the victim choices and control; collaborations via shared decision-making; exuding trustworthiness and prioritizing empowerment and skill-building (Buffalo Center for Social Research, 2019). A framework of this nature requires an organization and its staff to develop and implement policies and practices that do not re-traumatize those who it provides services to.

Input and direction from survivors. A primary assumption of this model is that no one understands sex trafficking better than a sex trafficking survivor. These women are believed to be experts on the subject matter because they have lived the life as trafficked victims who are now survivors. Her expertise is important as a survivor offering input, because she is able to garner trust among other survivors with similar lived experiences (Gerassi, 2018). This is particularly important given the stigma associated with prostitution, even when forced and outside the control of the victim. Prostitution in all forms is highly stigmatized in society and being around other survivors decreases the shame these women may feel—especially when the survivor can take on leadership roles in agencies offering services to her and her peers. Lloyd (2008) states that being able to lead others teaches survivors communication skills and the ability to speak up for oneself. From an empowerment perspective, seeing survivors further along in recovery provides a goal for other survivors to work towards. As for leadership, when survivors step up to leadership positions and are paid for these roles, it shows these women that they can be valued for more than their bodies and that they have a place in society (Lloyd, 2008). O’Hagan (2009) asserts that broad definitions of leadership are important and a respect for diversity of lived experiences is imperative.

Adequate resource allocation by the organization’s upper management. Due to the complexity of human trafficking and the ensuing trauma, it is important for organizations to be properly equipped with resources to offer proper treatment. This may include safe and long-term housing, food, medical treatment, psychological treatment, substance abuse treatment, and rehabilitation services (Palmiotto, 2014). Thus, multilateral support is required as well as the use of multiple agencies to supply survivors with comprehensive social services.

Empowerment of the survivor. Empowerment is essential to keeping the survivor in treatment. Lessons learned in treatment allow her to see that she is capable of recovery and rebuilding her life. As trafficking victims, women lose control over their lives in every way (when they eat, how they dress, where they live, how long they sleep, who they have sex with, how long they work, etc.) (Palmiotto, 2014). Treatment, however, helps to transfer that control and power back to the survivor. When a survivor gains agency in her life, it increases the likelihood that she will remain in treatment (Gerassi, 2018). From a theoretical perspective, anti-trafficking service is best expressed through the use of empowerment as a framework. Empowerment is an important goal when working with any client (Segal, Gerdes, & Steiner, 2007), but it is particularly important in the anti-trafficking arena where there is a need to empower a survivor of human trafficking to take control of her life. Empowerment strategies involve helping clients to gain individual power over one’s self, one’s actions, and one’s environment. It allows for self-determination and a transferring of power from external players and the environment to the client. It allows the trafficked person to shift her language from “victim” to “survivor”. The adoption of empowerment requires the clinician to understand the biography of the client so that her thoughts and actions are properly understood in the context in which the individual has experienced the world (Payne, 1997).

Post-graduation support. The effects of sex trafficking can last one’s entire life. To jump-start recovery, some sex trafficking victims participate in long-term treatment programs whereby she commits to lengthy (e.g.,18-24 months) and highly regulated service and treatment. Upon the successful completion of core requirements, participants are awarded certificates at a graduation. The CATCH court is one such program in Columbus, Ohio (Miner-Romanoff, 2015). Once graduating or discharging from a program, however, it is not inconceivable that a survivor will return to her trafficker. If in a stable environment that offers long-term support, however, survivors have a much lower chance of being re-trafficked (Twigg, 2017). Even if graduations and certificates are not part of a survivor’s regiment, supportive services after treatment are often cited as being needed post-trafficking (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012).

Recommendations

A Survivor Leadership model espouses that the sex trafficking victims-turned-survivors are experts and as experts should be given the opportunity to lead anti-trafficking efforts. The model purports that sex trafficking survivors know firsthand and up-close human traffickers—their recruitment strategies, their grooming practices, their violent tendencies, their weaknesses, their mentality, the tactics used to evade the law, and who they are as perpetrators. This makes them experts. They are key experts in understanding the mindset of traffickers, how to conduct outreach to survivors, how to outsmart traffickers, how to enact legislation that is victim-centered, how to offer victim-centered empowerment-based services, and address human trafficking in a practical and useful manner. Survivors are experts who must be heavily relied on, listened to, consulted with, and given a platform to use their leadership skills.

As a practitioner, it is imperative to always utilize the expertise of survivors when developing programming for this unique population. The 2019 Trafficking in Persons reports offers a check list (Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons, 2019) for establishing a survivor-informed practice.

Checklist for Establishing a Survivor-Informed Practice

- Assess the degree to which your organization is survivor-informed

- Identify gaps and opportunities

- Provide paid employment opportunities for survivors

- Staff positions

- Consultants

- Trainers

- Seek input from a diverse community of survivors

- Include both sex and labor trafficking perspectives

- Diversity in age, gender, race, national origin, sexual orientation, disability, etc.

- Create a plan for accessing survivor input throughout all stages of a project

- Program development and design (at inception is critical)

- Implementation

- Evaluation

Utilization of their skills and ideas include:

- Consulting with survivors at the onset of any potential programming ideas,

- Soliciting their suggestions as programming starts to unfold,

- Recruiting them as collaborators when offering services (e.g,. outreach, counseling, group activities, etc.), and

- Providing opportunities to develop and utilize leadership skills.

Quiz

Barbara Freeman, a Survivor and Leader in the Anti-Trafficking Movement

https://www.10tv.com/article/human-trafficking-survivor-honored-woman-achievement

Summary of Key Points

- Many sex trafficking survivors have the capacity to become leaders, especially in the anti-trafficking movement.

- A Survivor Leadership model is a five-part, survivor-centered model that focuses support and empowerment of the sex trafficked person

Supplemental Learning Materials

Administration for Children & Families. (2018, February). National Human Trafficking Training and Technical Assistance Center. Toolkit for Building Survivor-informed Organizations: Trauma-Informed Resources and Survivor-informed Practices to Support and Collaborate with Survivors of Human Trafficking as Professionals. Retrieved from https://freedomnetworkusa.org/app/uploads/2019/01/SurvivorWhitePaperDigitalFinalJan2019-1.pdf

Freedom Network USA. (2018, November). Human trafficking survivor leadership in the United States. Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/otip/toolkit_for_building_survivor_informed_organizations.pdf

Human Rights Funders Network. (2018, March 29). Survivor leadership in the anti-trafficking movement. Retrieved from, https://www.hrfn.org/event/survivor-leadership-in-the-anti-trafficking-movement/

Youth Laboratory. (2018, October 19). Victim-centered and survivor-led practices. Retrieved from https://youthcollaboratory.org/resource/victim-centered-and-survivor-led-practices

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Bengtsson, M. (2016). How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open, 2, 8–14.

Berg, B.L. (2008). Qualitative research methods for the social sciences: International edition (7th ed.). Harlow, Essex: Pearson: Allyn & Bacon.

Brodsky, A.E. (2014). Field notes: Sage Research Methods. Retrieved from http://srmo.sagepub.com/view/sage-encyc-qualitative-research-methods/n172.xml

Buffalo Center for Social Research. (2019). What is trauma-informed care? Retrieved from http://socialwork.buffalo.edu/social-research/institutes-centers/institute-on-trauma-and-trauma-informed-care/what-is-trauma-informed-care.html

Family and Youth Services Bureau. (2015). Runaway and Homeless Youth Training & Technical Assistance. Using a survivor leadership model to address human trafficking. Retrieved from http://www.chhs.ca.gov/Child%20Welfare/FYSB%20Survivor-led%20model.pdf

Farley, M. (Ed.). (2010). Prostitution, trafficking, and traumatic stress. New York: Routledge.

Gerassi, L.B. & Nichols, A.J. (2018). Sex trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation: Prevention, advocacy, and trauma-informed practice. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company, LLC.

Kara, S. (2009). Sex trafficking: Inside the business of modern slavery. New York: Columbia University Press.

Lloyd, R. (2008). From victim to survivor, from survivor to leader. Girls Education and

Mentoring Services, Gems. Retrieved from http://www.gems-girls.org

Miner-Romanoff, K. (2015). An evaluation study of a criminal justice reform specialty court –CATCH Court: Changing Actions to Change Habits: Full Report. Retrieved from https://services.dps.ohio.gov/OCCS/Pages/Public/Reports/CATCH%20FULL%20REPORT%20for%20Court%20CL%205.30.15.pdf

Office for Victims and Crimes—Training and Technical Assistance Center. (2018). Human trafficking task force e-guide. Retrieved from https://www.ovcttac.gov/taskforceguide/eguide/1-understanding-human-trafficking/13-victim-centered-approach/

Office of Justice Programs [OJP]. (2018). Justice for victims, justice for all. Retrieved from https://ovc.ncjrs.gov/humantrafficking/survivors.html/survivors.html

Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons. (2019, June 20). 2019 Trafficking in Persons report. Retrieved from https://www.state.gov/reports/2019-trafficking-in-persons-report/

O’Hagan, M. (2009). Leadership for empowerment and equality: A proposed model for mental health user/survivor leadership. International Journal of Leadership in Public Services, 5(4), 1-13.

Orme, J., & Ross-Sheriff, F. (2015). Sex trafficking: Policies, programs and services. Social Work, 60(4), 287-294.

Palmiotto, M.J. (2014). Combating human trafficking: a multidisciplinary approach. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Payne, M. (1997). Modern social work theory (2nd ed.)/. Lyceum Books, Inc: Chicago, IL.

Polaris. (2017). Hotline statistics. Retrieved from https://humantraffickinghotline.org/states

Public Law 106-386. (2000). Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000, H. R. 3244, (2000). 106th Cong., 2nd Sess.

Raymond, J.G., & Hughes, D.M. (2001). Sex trafficking of women in the United States: International and domestic trends. Retrieved from http://bibliobase.sermais.pt:8008/BiblioNET/upload/PDF3/01913_sex_traff_us.pdf

Ryan, G.W. (2014). What are standards of rigor for qualitative research? RAND Corporation. Retrieved from, http://www.wjh.harvard.edu/nsfqual/Ryan%20Paper.pdf

Segal, E.A., Gerdes, K.E., & Steiner, S. (2013). An introduction to the profession of social work: Becoming a change agent (4th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson—Brooks/Cole.

Sigmon, J.N. (2008). Combatting modern-day slavery: Issues in identifying and assisting victims of human trafficking worldwide. Victims and Offenders, 3, 245-257.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA]. (2014). Trauma definition. Retrieved from http://www.samhsa.gov/traumajustice/traumadefinition/definition.aspx

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA]. (2018). Trauma-Informed approach and trauma-specific interventions. Retrieved from, https://www.samhsa.gov/nctic/trauma-intervention

Twigg, N. M. (2017). Comprehensive care model for sex trafficking survivors. Journal

of Nursing Scholarship, 49 (3), 259-266.

U.S. Advisory Council. (2019 May). United States Advisory Council on Human Trafficking Annual Report 2019. Washington DC: US Department of State.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2012). Services available to victims of human trafficking: A resource guide for social service providers. Washington DC: Author.

Williamson, E., Dutch, N.M., & Clawson, H.J. (2007). Evidence-based mental health treatment for victims of human trafficking. Retrieved from http://aspe.hhs.gov/hsp/07/humantrafficking/mentalhealth/index.pdf