Chapter 9: Organ Trafficking

ABSTRACT

Organ trafficking is possibly one of the most covert forms of human trafficking. A global shortage of organs has driven the industry, relying on poor populations to be donors and wealthy foreigners to be recipients. In this chapter, the prevalence of organ trafficking will be explored, especially in relation to transplant tourism. Suggestions to stop trafficking will also be explored.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, the student will be able to:

- Define organ trafficking and transplant tourism

- Identify contributing factors to illegal organ trade

- Recognize countries commonly engaged in organ trafficking

- Have a basic understanding of efforts aimed at stopping organ trafficking

Key Words: Organ trafficking, transplant tourism

GLOSSARY

Organ Trafficking: The practice of using exploitation, coercion, or fraud to steal or illegally purchase or sell organs

Transplant Tourism: The act of traveling to a foreign country for the purpose of buying, selling, or receiving organs

Organ Trafficking

Over 114,000 people are on the organ waitlist in the United States, and a new person is added every 10 minutes (American Transplant Foundation, 2018). On average, 20 people die every day waiting for an available organ in the United States alone (American Transplant Foundation, 2018). The legally available organs for transplant only satisfy about 10% of the global organ transplant need (Negri, 2016, United Nations, 2018; Yousaf & Purkayastha, 2016). The long waitlists and grim results of waiting too long drive a lot of people to participate in transplant tourism and organ trafficking (ACAMSToday, 2018; American Transplant Foundation, 2018; Broumand & Saidi, 2017; United Nations, 2019). Organ trafficking is the practice of stealing or buying organs through exploitation to be sold on a black market for profit, and transplant tourism is traveling to another country for the purpose of buying, selling, or receiving organs (Broumand & Saidi, 2017; Shimazono, 2007; United Nations, 2011; United Nations, 2018).

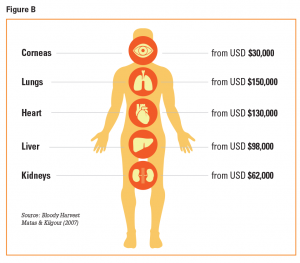

There is no reliable data on organ trafficking, but the World Health Organization (2004) believed it to be steadily on the increase, with brokers charging wealthy recipients $100,000+ and giving impoverished donors as little as $1,000, both amounts in U.S. dollars. It is also estimated that 10% of the organ transplants done globally are completed using black market organs (Negri, 2016; United Nations, 2018). Cultural and religious customs ban or discourage some individuals from donating organs willingly or receiving post-mortem organ donations (World Health Organization, 2004). Illegal organ harvesting generally is not harvesting organs from willing donors going against cultural laws for the sake of philanthropy, but harvesting from unwilling or uninformed donors through exploitation of impoverished, indebted, homeless, uneducated, and refugee people (United Nations, 2018). It is difficult to know exactly how many people have been victims or recipients of illegally harvested organs because of the complex nature of organ trafficking, like human trafficking in general, which leads to unreliable statistics and underreporting (Yousaf & Purkayastha, 2016).

Retrieved from https://bigthink.com/philip-perry/what-you-need-to-know-about-human-organ-trafficking

Targets of Organ Trafficking

Organ trafficking victims, as with most human trafficking victims, are generally poor, vulnerable populations (United Nations, 2018). There are rare instances where victims are put under anesthetic and wake to find their organs missing or are murdered for their organs. As a whole, coercion of living donors is more common (Future for Advanced Research and Studies, 2016; United Nations, 2011). It is most common for victims of organ trafficking to be recruited through brokers, who are individuals who recruit organ suppliers and connect them with organ recipients (Kelly, 2013; United Nations, 2011; United Nations, 2015). Recruiters/brokers are usually people who may be from the same communities or ethnicity of a vulnerable population so as to build trusting relationships easier. The recruiters then make promises to the organ suppliers like large sums of money or release from debt, and convince them that the organ is not needed. Specifically in the case of kidneys, the most commonly harvested organ from living donors, recruiters will tell victims that the kidney will grow back, having two kidneys is unnatural, or that they have a large and a small kidney and removal of the small kidney is harmless (United Nations, 2011; United Nations, 2015). Victims rarely receive the full amount of money promised, if they receive any compensation at all (United Nations, 2011; United Nations, 2015). In some cases, the post-removal healthcare costs for a living organ trafficking victim add to their previous debt and worsen their financial situation (Kelly, 2013).

Retrieved from https://www.acamstoday.org/organ-trafficking-the-unseen-form-of-human-trafficking/

There is a difference between “trafficking organs” and “trafficking persons for the purpose of organ removal”, which makes it difficult to combat both forms of trafficking and also to identify victims (United Nations, 2015).

TRAFFICKING ORGANS

Trafficking organs is an instance where the crime is buying and selling of organs, as a product, illegally.

vs.

TRAFFICKING PERSONS FOR THE PURPOSE OF ORGAN REMOVAL

Trafficking persons for the purpose of organ removal occurs when the person is the product and the purpose of trafficking them is for their organs.

Victims who “willingly” sell organs are sometimes treated as criminals involved in an illegal transaction, which would be trafficking in organs (Yousaf & Purkayastha, 2016). This criminalization is a deterrent for victims to pursue their compensation when they have been recruited and exploited by brokers.

The recipients of trafficked organs are generally wealthy, and participating in transplant tourism (European Union, 2015; United Nations, 2015). One study estimates that 70% of organ recipients are not registered organ donors, which some advocates argue is an unfair distribution of an already limited resource (Kelly, 2013). Recipients may have reached a point of desperation, cannot wait any longer for a legal donation, be deemed unsuitable for transplant domestically, or may not want to ask relatives for a living donation (United Nations, 2011; United Nations, 2015). Some recipients may even be unaware of organ trafficking and are responding to ads that seem legitimate from hospitals and medical professionals abroad that promise the organ transplant for one flat fee (United Nations, 2015).

Places and People

China is especially well-known for organ trafficking, with reports of prisons executing prisoners to illegally harvest their organs against their consent when they are a potential match for a recipient (Paul, Caplan, Shapiro, Els, Allison, & Li, 2017). The United States, Canada, the Czech Republic, and Israel have begun to take action to prevent their citizens from engaging in transplant tourism involving China (Doctors Against Forced Organ Harvesting (DAFOH), 2019). Alternatively, organ procurement through purchase in Iran is sometimes legal, as Iran is the only country in the world where it is legal to sell organs (Krishnan, 2018). Iran has established a base price for organs at $4,600, but that is only when the organs are procured legally–which is often not the case, as poor people still go through brokers and are paid an unknown, under-the-table price (Krishnan, 2018). One would hope that only a few isolated countries are major participants in organ trafficking, but unfortunately it is a global business where organs are bought from the poor and sold to the wealthy (European Union, 2015). Organ recipients participating in transplant tourism are mostly traveling from the United States, Canada, Saudi Arabia, the Gulf states, Japan, and Taiwan into Costa Rica, Panama, Ecuador, Colombia, Egypt, Kosovo, Cyprus, Israel, Azerbaijan, China, and the Philippines to receive organs (European Union, 2015). While not necessarily hot locations for transplant tourism, the following countries have been identified as organ recipients: Australia, Canada, Israel, Japan, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and the United States (Shimazono, 2007). India, Pakistan, China, Bolivia, Brazil, Iraq, Israel, Moldova, Peru, Turkey, and Colombia have all been identified as common organ sellers (Shimazono, 2007).

One of the difficulties with organ trafficking is the participation of the medical field and medical professionals in maintaining the industry (United Nations, 2011; United Nations, 2015; European Union, 2015). Doctors, nurses, ambulance staff, and entire hospitals participate in illegal organ harvesting and transplanting (European Union, 2015; United Nations, 2011; United Nations, 2015). The medical field is not the only industry upholding illegal organ trade, though. The United Nations (2011) cites that travel agents, insurance agents, and faith-based organizations that call on “organ hunters” also act as major players in maintaining the illegal buying and selling of harvested organs.

Action

In the United States, there have been 26 pieces of legislation passed aimed at regulating organ transplanting and donation (Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), n.d.). These regulations range from what constitutes being dead, to what constitutes consent for organ donation, to national honors for organ donation (HRSA, n.d.). In 1984 the United States passed the National Organ Transplant Act (NOTA), which banned the buying and selling of organs for transplant, created a task force on organ transplanting, and created an administrative unit in the Department of Health and Human Services to manage a registry of organ donors and recipients (HRSA, n.d.). The United States, however, remains a top recipient of trafficked organs (European Union, 2015; Shimazono, 2007). Additionally, the United States does not include organ removal in its definition of human trafficking in the Trafficking Victims Protection Act, and therefore has had few prosecutions related to organ trafficking—the prevalence of organ trafficking in the United States is difficult to estimate (Kelly, 2013).

The Declaration of Istanbul (2008) was drafted by over 150 representatives from 78 countries around the world to become the legal and professional framework for ethical practices of organ procurement and transplantation. The Declaration of Istanbul (2008) defined organ trafficking, transplant commercialism, and transplant tourism as well as gave specific guidelines for care, reimbursement, and recruitment of living donors. The revised 2018 edition of The Declaration of Istanbul further defines organ trafficking, specifically trafficking in persons for the purpose of organ removal, self-sufficiency in organ donation, and financial aspects of organ donation. Following the Declaration of Istanbul, the World Health Organization, the World Medical Association, and the European Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine have released guidelines and principals for the ethical obtainment of organs from consenting living and deceased donors, and ethical boundaries for medical professionals performing organ transplants (European Union, 2015). Unfortunately, though, none of these documents, with the exception of the European Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine, are legally binding, and the European Convention is only legally binding to those European member states that have signed and ratified it, leaving a very large portion of the world unaccountable (European Union, 2015). The Declaration of Istanbul (2018) calls on “designated authorities in each jurisdiction” (page 3) to ensure accountability and ethical practice. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2015) states that a lack of specific and adequate legislation is a major inhibitor to preventing trafficking in persons.

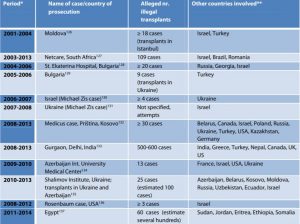

The United Nations Global Report on Trafficking in Persons (2018) states that the areas where human trafficking as a whole has decreased are countries that have adopted legislation, have detailed action plans, and are dedicated to identifying victims and perpetrators of trafficking. In regards to organ trafficking specifically, the United Nations (2018) highlights the importance of: coordination among United Nations entities in efforts against organ trafficking; taking on full implementation of provisions against organ trafficking; focusing on protection of vulnerable populations and preventing abuses of power; increasing efforts at identifying victims; and addressing international supply and demand and increasing awareness. Similarly, the European Union (2015) also created a series of recommendations to address organ trafficking. Specifically, they are: taking measures to address the legally obtained organ shortage; speed up implementation of national and international law; hold recipients criminally liable; address health professionals’ role in organ trafficking; improve organ traceability systems; prohibit payment for illegally obtained organs and seize criminal profits; and prohibit organ solicitation. See criminal cases below.

Recent international cases of organ trafficking

Source: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2015/549055/EXPO_STU%282015%29549055_EN.pdf

Quiz

Now, let’s shift gears and turn to a case study.

CASSANDRA

Cassandra is in need of a kidney donation due to persistent issues with kidney disease leading her to need hers removed and replaced. Cassandra is far down on the kidney waitlist, with an expected wait time of over a year and a half. Her husband does some research and finds a hospital in China that promises top doctors, state of the art medical facilities, a donor kidney, and the surgery for a flat fee of $50,000. The price is steep, but Cassandra and her husband believe they can get a second mortgage on their home to cover the cost and can afford the travel out of pocket. A few months after speaking with a representative from the hospital, they travel to China to have the surgery, stay for a few weeks of recovery, and then return home. Though they were unaware, the hospital they went through was involved with an underground, illegal organ trade business, and they had just engaged in transplant tourism. Cassandra was told that the kidney was from an “anonymous donor”, but in reality, there was a person who was exploited for their organ unwillingly.

Summary of Key Points

- Global organ trafficking is driven by an international shortage of organs and a growing number of deaths as a result of waiting too long for an organ.

- Organs generally come from vulnerable populations in countries with lax laws on organ trade, and go to recipients in wealthier countries.

Supplemental Learning Materials

Articles

Archer, D. (2013). Body snatchers: Organ harvesting for profit. Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/reading-between-the-headlines/201311/body-snatchers-organ-harvesting-profit

Martin, D., Van Assche, K., Dominguez-Gil, B., Lopez-Fraga, M., Gallont, R., …, Capron, A. (2019). Strengthening global efforts to combat organ trafficking and transplant tourism: Implications of the 2018 edition of the Declaration of Istanbul. Transplant Direct, 5(3). DOI: 10.1097/TXD.0000000000000872

Ralph, A., Alyami, A., Allen, R., Howard, K., Craig, J., Chadban, S., Irving, M., & Tong, A. (2016). Attitudes and beliefs about deceased organ donation in the Arabic-speaking community of Australia: A focus group study. BMJ Open, 6(1). DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010138

Report on organ harvesting in China’s prisons: Kigour, D., Gutmann, E., Matas, D. (2016). Bloody harvest/The slaughter: An update. Retrieved from https://endtransplantabuse.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Bloody_Harvest-The_Slaughter-June-23-V2.pdfSmall-Jordan, D. (2016). Organ harvesting, human trafficking, and the black market. Decoded Science. Retrieved from https://www.decodedscience.org/organ-harvesting-human-trafficking-black-market/56966

Srour, M. (2018). Human trafficking for organs: Ending abuse of the poorest. Inter Press Services News Agency. Retrieved from http://www.ipsnews.net/2018/04/human-trafficking-organs-ending-abuse-poorest/

Videos

Harvested Alive Documentary: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Od3Q6O7HMy8

Famous Cases

Kendrick Johnson Case: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/kendrick-johnson-death-missing-organs-are-reason-to-suspect-foul-play-in-ga-teens-gym-mat-death-victims-parents-say/

Chinese boy’s eyes gouged out: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-23846633

Books

Opportunities for Organ Donor Intervention Research: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK458645/

Websites

www.dafoh.org

www.humantraffickingsearch.org

References

ACAMSToday. (2018). Organ Trafficking: The Unseen Form of Human Trafficking. Retrieved from https://www.acamstoday.org/organ-trafficking-the-unseen-form-of-human-trafficking/

American Transplant Foundation. (2018). Facts: Did you know? Retrieved from https://www.americantransplantfoundation.org/about-transplant/facts-and-myths/

Broumand, B. & Saidi, R. (2017). New definition of transplant tourism. International Journal of Organ Transplant Medicine, 8(1), 49-51. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5347406/

Doctors Against Forced Organ Harvesting (DAFOH). (2019). The United States, Canada, the Czech Republic, and Israel Act Against Organ Trafficking. Retrieved from https://dafoh.org/newsletter/the-united-states-canada-the-czech-republic-and-israel-act-against-organ-harvesting/

European Union. (2015). Trafficking in Human Organs. European Union Directorate-General for External Policies Policy Department. Retrieved from http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2015/549055/EXPO_STU%282015%29549055_EN.pdf

Future for Advanced Research and Studies. (2016). Why rates of human trafficking are on the rise in the Middle East. Retrieved from https://futureuae.com/m/Mainpage/Item/2309/why-rates-of-human-organ-trafficking-are-on-the-rise-in-the-middle-east

Health Resources and Services Administration. (n.d.). Selected Statutory and Regulatory History of Organ Transplantation. Retrieved from https://www.organdonor.gov/about-dot/laws/history.html

Kelly, E. (2013). International organ trafficking crisis: Solutions addressing the heart of the matter. Boston College Law Review, 54(3), Article 17. Retrieved from https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://scholar.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=3324&context=bclr

Krishnan, M. (2018). Legalizing trafficking: Iran’s unjust organ market and why legal selling of organs should not be the resolve. Berkeley Political Review. Retrieved from https://bpr.berkeley.edu/2018/05/03/legalizing-trafficking-irans-unjust-organ-market-and-why-legal-selling-of-organs-should-not-be-the-resolve/

Negri, S. (2016). Transplant ethics and the international crime of organ trafficking. International Criminal Law Review, 16(2016), 287-303. DOI 10.1163/15718123-01602001

Paul, N., Caplan, A., Shapiro, M., Els, C., Allison, K., & Li, H. (2017). Human rights violations in organ procurement practice in China. BMC Medical Ethics, 18(11). DOI: 10.1186/s12910-017-0169-x

Ralph, A., Alyami, A., Allen, R., Howard, K., Craig, J., Chadban, S., …, Tong, A. (2016). Attitudes and beliefs about deceased organ donation in the Arabic-speaking community in Australia: a focus group study. BMJ Open, 6(1). Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4735320/

Shimazono, Y. (2007). The state of the international organ trade: a provisional picture based on integration of available information. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 85(12), 901-980. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/85/12/06-039370/en/

Steering Committee of the Istanbul Summit. (2008). The Declaration of Istanbul on Organ Trafficking and Transplant Tourism (2008 Edition). Retrieved from https://www.declarationofistanbul.org/images/Policy_Documents/2008_Edition_of_the_Declaration_of_Istanbul_Final.pdf

Steering Committee of the Istanbul Summit. (2018). The Declaration of Istanbul on Organ Trafficking and Transplant Tourism (2018 Edition). Retrieved from http://www.declarationofistanbul.org/images/Policy_Documents/2018_Ed_Do/2018_Edition_of_the_Declaration_of_Istanbul_Final.pdf

United Nations. (2011). Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime. Working Group on Trafficking in Persons. Vienna. Retrieved from https://www.unodc.org/documents/treaties/organized_crime/2011_CTOC_COP_WG4/2011_CTOC_COP_WG4_8/CTOC_COP_WG4_2011_8_E.pdf

United Nations. (2015). Assessment Toolkit: Trafficking in Persons for the Purpose of Organ Removal. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Retrieved from https://www.unodc.org/documents/human-trafficking/2015/UNODC_Assessment_Toolkit_TIP_for_the_Purpose_of_Organ_Removal.pdf

United Nations. (2018). Global Report on Trafficking in Persons. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Retrieved from https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/glotip/2018/GLOTiP_2018_BOOK_web_small.pdf

United Nations. (2019). Organ Trafficking. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Retrieved from https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/organized-crime/intro/emerging-crimes/organ-trafficking.html

World Health Organization. (2004). Organ trafficking and transplantation pose new challenges. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 82(9). Retrieved from https://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/82/9/feature0904/en/

Yousaf, F., Purkayastha, B. (2016). Social world of organ transplantation, trafficking, and policies. Journal of Public Health Policy, 37(2), 190-199. DOI: 10.1057/jphp.2016.2