Chapter 12: Identifying Trafficking Victims in Healthcare Settings

ABSTRACT

The healthcare industry has an important and unique role to play in the identification and service of trafficked persons. Understanding the signs of sex and labor trafficking are first steps in the positive identification of a trafficked person. This chapter will discuss the warning signs and red flags associated with sex and labor trafficking.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, the student will be able to:

- Understand the implications of ACEs for sexual victimization

- Identify risk factors for trafficking

- Identify red flags for sex and labor trafficking

- Describe a potential protocol for assisting trafficking victims in healthcare settings

Key Word: Adverse Childhood Experiences

GLOSSARY

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs): The term used to describe abuse (physical, emotional and sexual), neglect (physical and emotional), and other potentially traumatic experiences that occur to minors less than 18 years of age. This 10-item scale ranges from 0-10 points. The higher number of ACEs, indicates greater risk for vulnerability

Adverse Childhood Experiences

According to the Center for Disease Control (2019), Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) is the term used to describe abuse, neglect, and other potentially traumatic experiences that occur to victims less than 18 years of age. Adverse Childhood Experiences include 10 dimensions: 1) physical abuse; 2) emotional abuse; 3) sexual abuse; 4) physical neglect; 5) emotional neglect; 6) substances in the home;7) parental separation/divorce; 8) mental illness; 9) a battered mother; and 10) criminal behaviors/incarceration of family members. The 10 ACEs are assessed using a 10 item scale that results in a total score of 0-10. [See Table 1 for ACEs questions.] As the number of ACEs increases, so does the risk for risky health behaviors, chronic health conditions, and early death. Specifically, the ACEs quiz asks the following questions:

ADVERSE CHILDHOOD EXPERIENCES (ACEs)

Prior to your 18th birthday:

- Did a parent or other adult in the household often or very often… Swear at you, insult you, put you down, or humiliate you? or Act in a way that made you afraid that you might be physically hurt?

No___If Yes, enter 1 __ - Did a parent or other adult in the household often or very often… Push, grab, slap, or throw something at you? or Ever hit you so hard that you had marks or were injured?

No___If Yes, enter 1 __ - Did an adult or person at least 5 years older than you ever… Touch or fondle you or have you touch their body in a sexual way? or Attempt or actually have oral, anal, or vaginal intercourse with you?

No___If Yes, enter 1 __ - Did you often or very often feel that … No one in your family loved you or thought you were important or special? or Your family didn’t look out for each other, feel close to each other, or support each other?

No___If Yes, enter 1 __ - Did you often or very often feel that … You didn’t have enough to eat, had to wear dirty clothes, and had no one to protect you? or Your parents were too drunk or high to take care of you or take you to the doctor if you needed it?

No___If Yes, enter 1 __ - Were your parents ever separated or divorced?

No___If Yes, enter 1 __ - Was your mother or stepmother:

Often or very often pushed, grabbed, slapped, or had something thrown at her? or Sometimes, often, or very often kicked, bitten, hit with a fist, or hit with something hard? or Ever repeatedly hit over at least a few minutes or threatened with a gun or knife?

No___If Yes, enter 1 __ - Did you live with anyone who was a problem drinker or alcoholic, or who used street drugs?

No___If Yes, enter 1 __ - Was a household member depressed or mentally ill, or did a household member attempt suicide? No___If Yes, enter 1 __

- Did a household member go to prison?

No___If Yes, enter 1 __

Scores range from 0-10 based on “No” or “Yes” responses (ACEs Too High News, 2019).

Figure 1. Adverse Childhood Experiences

As shown in Figure 1, Adverse Childhood Experiences put a person at risk for physical injuries, mental health problems, maternal health challenges, infectious diseases, chronic diseases, chronic health problems, risky behaviors and poor socioeconomic statuses (CDC, 2019). ACEs have also been linked to early death (CDC, 2019).

Figure 1. Early Adversity Has Lasting Impacts – Diagram courtesy of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Violence Prevention: About ACEs. Retrieved from

https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/acestudy/aboutace.html

Specific to sex trafficking, ACEs have been linked to risky behaviors that include alcohol and other drugs as well as unsafe sex. As previously stated in this text, human traffickers use drugs to lure in potential trafficking victims with an already established substance use disorder. They also use drugs to entice or lure in an inexperienced victim to get her “hooked” on drugs. Once dependent on drugs, drugs are often used as a reward (for compliance) as well as a punishment for non-compliance for trafficked women. In the case of non-drug using victims, the trafficker sometimes forces the consumption of addictive substances because it will guarantee the trafficker that: 1) the victim will become dependent; 2) drug dependencies will make the victim incur debt to the trafficker; 3) the trafficker will be able to control the victim through drug use; and 4) the victim may become unduly influenced to stay in a trafficked situation due to trauma bonding (and drug dependence) despite how bad the trafficking experience may be (Bernat & Winkfeller, 2010; Kara, 2009; Meshelemiah, Gilson & Prasanga, 2018; Williamson, Dutch & Clawson, 2007). Drug use also ensures more cooperation on the victim’s part. In the case of sex trafficked persons, ACEs and substance use disorders appear to interact with one another.

Ports, Ford and Merrick (2016) found that as one’s ACEs score increased, so did the risk of experiencing sexual victimization later in adulthood. Each of the ACEs variables was significantly associated with adult sexual victimization with childhood sexual abuse being the strongest predictor of adult sexual victimization. Additionally, the results of their study indicate for those who reported childhood sexual abuse, there was a cumulative increase in adult sexual violence risk with each additional ACEs experienced. This relationship suggests that early adversity is a risk factor for adult sexual victimization. In terms of prevention, given the interconnectedness between childhood adversity and adult sexual victimization, practitioners must take into consideration how other violence-related and non-violence-related traumatic experiences may exacerbate the risk conferred by childhood sexual abuse on later victimization in adulthood.

ACEs and Physical Disorders

Categorically, Adverse Childhood Experiences have also been linked to the following classes of physical disorders along with mental disorders. According to Lederer and Wetzel (2014), these same types of disorders are commonly found among sex trafficking survivors.

- Neurologic

- Gastrointestinal

- Cardiovascular

- Musculoskeletal

- Dermatological

- Reproductive

- Sexual

- Dental

- Mental Health (including substances)

Red Flags of Trafficking

In terms of identification of trafficked persons in healthcare settings, the following are red flags in a patient’s presentation when sex trafficked (Greenbaum, Dodd & McCracken, 2018; Orme & Ross-Sheriff, 2015).

- Broken bones

- Traumatic brain injury & concussions

Risk Factors make people vulnerable to be being trafficked while Red Flags are signs of being trafficked (Schwarz, Unruh, Cronin, Evans-Simpson, Britton & Ramaswamy, 2016).

- Back & stomach pain

- Exhaustion

- Malnutrition

- Burns

- Hepatitis

- HIV/AIDS

- Vaginal tearing

- Multiple sexually transmitted infections (STIs)

- Pelvic inflammatory disease

- Unplanned pregnancies

- Miscarriages/abortions

The following are red flags in a patient’s presentation when labor trafficked (National Human Trafficking Resource Center, 2019; Office on Trafficking in Persons, 2019; Orme & Ross-Sheriff, 2015).

- Body injuries

- Back pain

- Exhaustion

- Respiratory illnesses

- Hypothermia

- Amputations

- Heat stroke

- Dehydration

- Skin infections

- Chemical burns from pesticides

Mental Disorders

According to the most current version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) of Mental Disorders, trafficking victims are especially at high risk for developing Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), which is a mental disorder (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). Substance disorders are also found in this particular Manual. Commonly used drugs by sex trafficked persons include alcohol, crack cocaine, and heroin (and other opioids). The misuse of these highly addictive drugs tends to result in substance use disorders (Greenbaum, Dodd & McCracken, 2018; Orme & Ross-Sheriff, 2015). In addition to substance use disorders, the following classifications of mental disorders tend to present among trafficked persons as well (Greenbaum, Dodd & McCracken, 2018). They include:

ARTICLE 25

Healthcare is a human right.

- Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD),

- Anxiety/panic disorders,

- Depressive disorders,

- Insomnia/sleep disturbances,

- Dissociative disorders,

- Somatic symptoms, and

- Suicidal ideations and attempts.

Victims are Not Invisible: Know the Signs

The physical and mental disorders just discussed are common disorders that present among sex and labor trafficked persons in healthcare settings. In their study, Lederer and Wetzel (2014) found that 99.1% of their 106 trafficking survivors reported to a healthcare facility while a trafficking victim with at least one physical health problem. Other researchers have found similar findings. Greenbaum, Dodd and McCkracken (2018) reported that 108 minors reported to two metropolitan pediatric emergency departments and one child protection clinic in their study. This indicates that trafficked adults and children are not always hidden or invisible. Trafficked children and adults have sought treatment from emergency rooms, free clinics, child protection clinics, pediatric emergency departments, hospitals, private physicians, and clinical treatment facilities (Greenbaum, Dodd & McCkracken, 2018; Schwarz, Unruh, Cronin, Evans-Simpson, Britton & Ramaswamy, 2016). Given this reality, it is critical that healthcare practitioners are better prepared to identify victims when they seek healthcare.

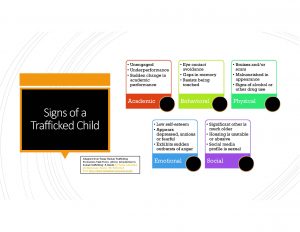

According to the Texas Human Trafficking Prevention Task Force (2014), signs of a school-aged child being trafficked includes academic, behavioral, physical, emotional, and social indicators as shown below.

According to Polaris (2019), signs of labor and sex trafficking include work-related conditions, mental health/behavioral flags, physical health flags, lack of control, and other indicators as shown below.

Screening for Child Sex Trafficking Victims in Healthcare Settings

In an effort to screen child sex trafficking in the healthcare setting, a group of researchers developed a Brief Screening Tool (Greenbaum, Dodd, & McCkracken, 2018). The following questions compose the tool:

- Is there a previous history of drug and/or alcohol use?

- Has the youth ever run away from home?

- Has the youth ever been involved with law enforcement?

- Has the youth ever broken a bone, had a traumatic loss of consciousness, or sustained a significant wound?

- Has the youth ever had an STI?

- Does the youth have a history of sexual activity with more than 5 partners?

Greenbaum, Dodd and McCkracken (2018) found that answering “yes” to just two of these questions properly identified child sex trafficked victims with a sensitivity of 92%, specificity of 73%, positive predictive value (PPV) of 51%, and a non-positive predictive value of 97%. These percentages mean that this is a useful tool for early screening of child sex trafficking in a healthcare setting.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (n.d.) recommends that healthcare providers discretely ask the following questions to suspected victims of human trafficking. Confidentiality should be ensured and the questions asked should be in the language of the person spoken to. The following questions should be asked after rapport is developed and the patient appears comfortable asking questions.

- Can you leave your job or situation if you want?

- Can you come and go as you please?

- Have you been threatened if you try to leave?

- Have you been physically harmed in any way?

- What are your working or living conditions like?

- Where do you sleep and eat?

- Do you sleep in a bed, on a cot, or on the floor?

- Have you ever been deprived of food, water, sleep, or medical care?

- Do you have to ask permission to eat, sleep, or go to the bathroom?

- Are there locks on your doors and windows so you cannot get out?

- Has anyone threatened your family?

- Has your identification or documentation been taken from you?

- Is anyone forcing you to do anything that you do not want to do?

Detecting red flags for children and adults is an important first step in providing services to trafficked persons in healthcare settings. Despite the healthcare model used in the United States and many other countries around the world, access to healthcare is a human right—not a privilege.

Barriers to Disclosure

Despite the care and attentiveness of the most well-meaning healthcare practitioner, the individual may not be successful at getting trafficked persons to open up in some instances. According to researchers (Baldwin, Eisenman, Sayles, Ryan & Chuang, 2011; Greenbaum, Dodd, & McCkracken, 2018; Orme & Ross-Sheriff, 2015), there are a host of barriers to disclosure of trafficking victimization. They include:

- Feelings of shame,

- Trauma bonding with the trafficker,

- The victim being trained to “lie”,

- A sense of hopelessness,

- Language barriers,

- Distrust of authorities,

- Fear of the trafficker or legal authorities [being arrested],

- Presence of the trafficker [accompanies victim to healthcare facility], and

- Lack of self-identification as a trafficking victim.

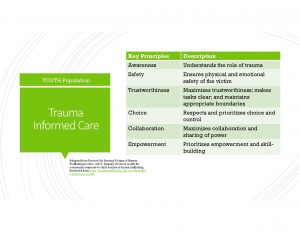

In the event that the healthcare practitioner is able to get the trafficked person to open up, it is important to adhere to a trauma-informed protocol to avoid re-traumatizing the victim. All practitioners seeking to screen, identify, and assist trafficked persons should seek professional development training on trauma informed care. Trauma-informed care is one that recognizes the impact of trauma on one’s mental health, physical health, social capacity, and brain development (Enrile & De Castro, 2019). Key principles include awareness, safety, trustworthiness, choice, and collaboration.

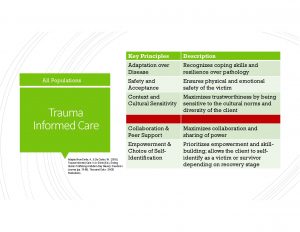

The above table is specified for youth, but is appropriate for adults as well. According to Enrile and De Castro (2018), evidence-based and evidence-informed practices for trauma-informed care points to 1) safety and acceptance; 2) adaptation over disease; 3) collaboration and peer support; and 4) empowerment/choice of self-identification; and 5) context and cultural sensitivity. These concepts overlap with the trauma informed youth approach to service delivery.

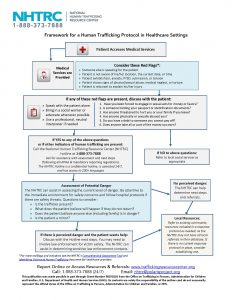

National Human Trafficking Resource Center (NHTRC) Framework for HT Protocol in Healthcare Settings

Healthcare practitioners must advocate for hospital level policies that incorporate a protocol for suspected cases of sex and labor trafficking. The framework must be multidisciplinary in nature and include the following practitioners when possible:

- Physicians,

- Nurses,

- Social workers,

- Pastoral care,

- Addiction specialists,

- Behavioral health personnel,

- Anti-trafficking task forces,

- Local law enforcement,

- Local social service agencies, and

- U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) [as appropriate].

As seen in the diagram below, there are proper steps to take that include knowing red flags, discussing them with the patient, calling the National Human Trafficking Resource Center if indicators are present, assessing the level of potential danger, and then deciding if law enforcement involvement is needed or a referral to local resources. Regardless of one’s discipline, Baldwin et al. (2011) recommends that all practitioners in healthcare settings use good common sense, notice visual cues, observe patients’ body language and interact with patients in a sensitive manner. Being indifferent and too busy are not acceptable alternatives.

Quiz

Now, let’s shift gears and turn to a case study.

MAXI

WARNING: GRAPHIC CONTENT!!

“Maxi” is a young African American female who was sex trafficked for over 10 years. She participated in a research project in 2019 conducted by the authors. This is a description of a medical emergency of hers.

Despite bleeding through her jeans due to a miscarriage that turned into hemorrhaging, Maxi continued to smoke crack and “turn tricks” for two hours before she passed out and nearly died due to blood loss. Several male customers asked for and paid for a “blow job” while Maxi knelt down with blood soaked jeans on. One even wanted vaginal sex with her despite her heavy bleeding, but she refused. It was not until another sex trafficked woman who had been smoking crack cocaine with Maxi earlier in a “trap house” began to insult her for being so “trifling” for not going to see a doctor after clearly miscarrying her fetus, that Maxi finally decided to seek medical care.

The woman warned her that she was going to bleed to death if she did not seek medical attention right away. It was at that point that Maxi decided to seek out a police officer for help. As she approached the law enforcement officer’s vehicle, she passed out from blood loss.

Maxi reports that not one healthcare provider screened her for sex trafficking while hospitalized after her miscarriage. Instead, she reports, that they concluded that she was a “junkie” who needed substance use treatment and later discharged her. Despite this horrific loss, Maxi continued to use drugs for many years after this miscarriage and near death experience. Her pimp trafficked her for many years as well.

Summary of Key Points

- According to Article 25 of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights, access to healthcare is a human right.

- It is critical that healthcare providers better identify and are better prepared to serve trafficking victims when they seek medical care. Below are a list of resources that may be helpful.

Supplemental Learning Materials

References

ACEsTooHighNews. (2019). Got your CE Score. Retrieved from https://acestoohigh.com/got-your-ace-score/

Baldwin, S.B., Eisenman, D.P., Sayles, J.N. Ryan, G., & Chuang, K.S., (2011). Identification of human trafficking victims in healthcare settings. Health & Human Rights, 13(1), 1-14.

Bernat, F.P., & Winkeller, H.C. (2010). Human sex trafficking: The global becomes local. Women & Criminal Justice, 20, 186-192.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, April 9). About adverse childhood experiences. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/acestudy/aboutace.htmlEnrile, A., & De Castro, W. (2018). Trauma Informed Care. In A. Enrile (Ed.), Ending Human Trafficking & Modern-Day Slavery: Freedom’s Journey (pp. 79-98). Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Greenbaum, V.J., Dodd, M., & McCkracken, C. (2018). A short screening tool to identify victims of child sex trafficking in the healthcare setting. Pediatric Emergency Care, 34(1), 33-37;

Kara, S. (2009). Sex trafficking: Inside the business of modern slavery. New York: Columbia University Press.

Lederer, L.J., & Wetzel, C.A. (2014). The health consequences of sex trafficking and their implications for identifying victims in healthcare facilities. Annals of Health Law, 23, 61-90.

Meshelemiah, J.C.A., Gilson, C., & Prasanga, A.P.A. (2018). Use of drug dependency to entrap and control victims of human trafficking: A call for a US federal human rights response. Dignity: A Journal on Sexual Exploitation and Violence, 3(3), Article 8.

Meshelemiah, J.C.A., Poole, A.L., & Michel, E. (Winter 2013). Creating a standard protocol for Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking Victims: How child welfare workers can better facilitate protections under the guise

of the TVPA. Washington, DC: NASW.

National Human Trafficking Resource Center. 2019). (Identifying victims of human trafficking: What to look for in a healthcare setting. Retrieved from https://humantraffickinghotline.org/sites/default/files/What%20to%20Look%20for%20during%20a%20Medical%20Exam%20-%20FINAL%20-%202-16-16.pdf

Office on trafficking in persons. (2019, February 4). National advisory council on migrant health: Recommendations on labor trafficking. Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/otip/news/nacmh-0

Orme, J., & Ross-Sheriff, F. (2015). Sex trafficking: Policies, programs, and services. Social Work, 60(4), 287-294.

Polaris. (2019). Recognize the signs. Retrieved from https://polarisproject.org/human-trafficking/recognize-signs

Ports, K.A., Ford, D.C., & Merrick, M.T. (2015). Adverse childhood experiences and sexual victimization in adulthood. Epub, 51, 313-322. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.08.017

Protocol for Serving Victims of Human Trafficking in Ohio. (2017, August). Protocol toolkit for community response to child victims of human trafficking. Retrieved from https://humantrafficking.ohio.gov/links/HT-Child-Protocol.pdf

Roudometkina, A. & Wakeford, K. (15 June 2018). National Women’s Association of Canada. Trafficking of Indigenous Women and Girls in Canada: Submission to the Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights. Retrieved from https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/421/JUST/Brief/BR10002955/br-external/NativeWomensAssociationOfCanada-e.pdf

Schwarz, C., Unruh, E., Cronin, K., Evans-Simpson, S., Britton, H., & Ramaswamy, M. (2016). Human trafficking identification and service provision in the medical and social service sectors. Health and Human Rights Journal, 18(1), 181-192.

Texas Human Trafficking Prevention Task Force. (2014). Introduction to human trafficking: A Guide for Texas education professionals. Austin, TX: Retrieved from http://www.texasattorneygeneral.gov

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Resources: Screening tool for victims of human trafficking. Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/orr/screening_questions_to_assess_whether_a_person_is_a_trafficking_victim_0.pdf

Williamson, E., Dutch, N.M., & Clawson, H.J. (2007). Evidence-based mental health treatment for victims of human trafficking. Retrieved from http://aspe.hhs.gov/hsp/07/humantrafficking/mentalhealth/index.pdf