Chapter 4: Sex Trafficking

ABSTRACT

Forced prostitution in sex trafficking is the most common perception of what human trafficking is. Forced prostitution, however, is not the only way a person can be trafficked for sex. In this chapter, forced prostitution is explored along with pornography, the male entertainment industry, and Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking (DMST).

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, the student will be able to:

- Define sex trafficking and understand who the most common victims are

- Understand the various ways that sex trafficking may present

- Understand the unique problem of Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking

Key Words: Sex Trafficking, Prostitution, Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking, Pimp

GLOSSARY

Sex Trafficking: The recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, or obtaining of a person for the purpose of a commercial sex act (CSA), in which a CSA is induced by force, fraud, or coercion, or in which the person induced to perform such act has not attained 18 years of age

Prostitution: The act of engaging in sexual intercourse or performing sexual favors for money or other things of value

Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking: The commercial sexual exploitation of American children within U.S. borders

Pimp: The person exploiting a prostitute or sex trafficked person; considers themselves an owner of the person; generally, lives off of the profits generated by the person who is prostituted or sex trafficked

John: A buyer of sex

Sex Trafficking

Sex trafficking in the United States, according to the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA), is “the recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, or obtaining of a person for the purpose of a commercial sex act (CSA), in which a CSA is induced by force, fraud, or coercion, or in which the person induced to perform such act has not attained 18 years of age” (Trafficking Victims Protection Act, 2000, p. 8). Globally, the United Nations in its “Protocol” defines human trafficking as the following, specifically mentioning the inclusion of exploitation through sex at the end:

“the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs” (United Nations, 2003, Article 3, page 43).

Statistics

Labor trafficking is the most common form of human trafficking globally, but sex trafficking and debt bondage trail close behind (San Francisco Human Rights Commission, n.d.). Sex trafficking, though, is the most detected form of human trafficking globally (United Nations, 2018). It was estimated that in 2016, 4.8 million women, men, and children were trapped being trafficked for the purpose of sexual exploitation around the world (International Labor Organization, 2017). Sexual exploitation is the most common form of human trafficking in the Western hemisphere and makes up 71% of identified victims (United Nations, 2018). In 2016, 68% of all identified human trafficking victims in North America were identified within their own countries borders, meaning most trafficking is domestic, contrary to popular beliefs held about trafficking victims being foreign women and children kidnapped (United Nations, 2018). The United States specifically was ranked as a Tier 1 country by the U.S. Department of State’s Annual Trafficking in Persons report (2018), meaning the government was in full compliance of the minimum requirements put forth by the TVPA. However, domestic human trafficking continues to be a major problem in the United States, with California, Texas, Florida, and Ohio ranked as the top 4 states in the country for reports of human trafficking, with 75.26%, 70.99%, 71.11%, and 81.27% of cases being sex trafficking, respectively (Human Trafficking Hotline, 2017). Sex trafficking in the United States is estimated to be a $3-billion-dollar industry every year, with major sporting events like the Super Bowl and other events that are male-oriented, as hubs for increased sex trafficking activity, sometimes drawing up to three times the volume of sex trafficking (O’Day, 2018). Feeding that $3-billion-dollar industry, the United Nations (2018) estimates that in North America, the expected criminal income per case of sexual exploitation is $390 per day.

“Money” by free pictures of money is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Forced Prostitution

Forced prostitution is the most commonly known form of human trafficking in general (San Francisco Human Rights Commission, n.d.). Forced prostitution victims are recruited, controlled, and exploited in many ways and by a number of people. Generally, victims are women and girls, with approximately 83% of identified women human trafficking victims and 72% of identified female child victims being trafficked for the purpose of sexual exploitation, as opposed to 10% of men and 27% of boys (United Nations, 2018). Girls, on average, are recruited between the ages of 12-14 for forced prostitution, although some are much younger, with many of them having been sexually abused as children and left in a vulnerable position (Kotrla, 2010; Shared Hope International, 2019). While there is no set profile of a victim, there are people who are considered more at risk of forced prostitution. For forced prostitution victims, the complex risks of drug or substance use, poverty, history of abuse, age, and marginalized identities is important to note. Women (especially women of color), immigrants, LGBTQ individuals, homeless or runaway youth, and domestic violence and sexual assault victims are common recruits and victims of sex trafficking (Lillie, 2014; National Human Trafficking Hotline, n.d.A.; Polaris, 2017). The venue of forced prostitution is not limited just to the streets where it is commonly believed that sex workers will be found. It is more common for forced prostitution to occur in homes and “businesses” than on the streets (Stark & Hodgson, 2003). Erotic massage parlors, health or beauty fronts, and escort services are common businesses where forced prostitution is masked as a legitimate service (Polaris, 2017). Victims may either be forced to provide sexual favors to patrons, be unpaid or underpaid for their services, or a combination of both (Polaris, 2017).

Pimps are Traffickers

The “owners” of individuals forced into prostitution are commonly called pimps and traffickers. They are the perpetrators who control the actions and live off the profits of the people they prostitute (Grough & Goldbach, 2010). Contrary to common beliefs about pimps, traffickers are not only strangers who kidnap women and children, but they are more likely to be intimate partners, family members, acquaintances, or friends of victims—especially in the case of minors (National Human Trafficking Hotline, n.d.B.; Reed, Kennedy, Decker, & Cimino, 2019; Smith, Vardaman, & Snow, 2009) The pimps use tactics similar to those of domestic violence batterers to control their victims–isolation of the victim, minimizing or denying abuse, threats and intimidation, and physical, emotional, and sexual abuse (Stark & Hodgson, 2003). Not surprisingly, forced prostitution is heavily interrelated with domestic violence. The Polaris Project’s Human Trafficking Power and Control Wheel is based off a domestic violence model of power and control, and highlights how a trafficker can exploit a family member or intimate partner, and how even mimicked familial or relationship ties can strengthen a victim’s loyalty to their trafficker making the exploitative situation even more complicated and harder to leave (Cody, 2017). In addition to physical and verbal abuse of intimate partners or the creation of relationships that seem loving, pimps may use pre-existing drug addiction, or create a drug addiction, as a means of control over the victims (Currier & Feehs, 2019). Over a third of sex trafficking cases in 2018 reported exploitation of substance use issues by traffickers to control victims (Currier & Feehs, 2019). Victims with a pre-existing drug addiction believe that this is just part of their addiction and they have hit an all-time “low” in their use. Victims whose drug addiction is created by their pimps begin thinking that this is what they deserve for getting caught up in drug use. Both lines of thinking are beneficial to the pimp, as the victims place blame on themselves for their situation instead of their abuser, making them less likely to seek help (Meshelemiah & Lynch, 2019).

“drugs” by gregorfischer.photography is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

The buyers of forced prostitution are generally men, called johns or tricks, and they keep the sex trafficking industry alive. Without buyers, there would be no forced prostitution. In a study comparing online sex buyers to a national sample of men, researchers found that buyers were generally White (69.5%), working full-time (60.3%), had completed high school (53.2%), and married (51.8%) (Monto & Milrod, 2014). The researchers found that there is no peculiar quality that makes men who have purchased sex any different from men who have not (Monto & Milrod, 2014). The prostituted women and girls who are battered, raped, and murdered by tricks and johns know that the men who exploit them are just average, everyday men (Stark & Hodgson, 2003). Many of the biggest consumers of prostitution are from developed nations, and two out of every three men who pay for sex are aware that the majority of sex workers are trafficked (Fight the New Drug, 2018).

Unfortunately, the trauma of forced prostitution victims often does not end at the pimps and johns. It is common for victims to have a criminal history riddled with prostitution charges, drug charges, theft, or charges for crimes their traffickers forced them to commit, which makes accessing employment, housing, and other resources more difficult, sometimes forcing victims to go back to their traffickers (Farmand, n.d.; Ohio Justice and Policy Center, n.d.). This has caused a stir in discussions about the re-victimization and trauma of trafficking victims by the criminal justice system. It is also common for law enforcement officials to be untrained in identifying and helping victims, and for traffickers to train victims on what to say in the case of an arrest, causing further complications in assisting victims when they enter the criminal justice system (Farmand, n.d.; Ohio Justice and Policy Center, n.d.). Victims also usually have a distrust of the criminal justice system, either because of previous negative experiences, or because traffickers have made them believe that they will go to jail, be deported, or the traffickers themselves will inflict harm on the victim or their loved ones if they go to law enforcement (Department of Health and Human Services, n.d.; Hopper & Hidalgo, 2006; Ohio Justice and Policy Center, n.d.).

Barnellbe [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]

Male Entertainment Industry/Pornography

When thinking about human trafficking, sometimes images from popular media come to mind. In the case of sex trafficking, there is a scene in the film Taken (2008), where Liam Neeson’s American daughter is kidnapped in France, drugged, dancing in a glass case in lingerie, and about to be sold to the highest bidder. While an example like this is not an accurate portrayal of commercial sex exploitation of American girls and women, the idea that women and girls are trafficked to fuel the male entertainment industry and pornography holds some truth. Most of the pornographic industry is online, and many of the women who act in the films are coerced or forced (Luzwick, 2017). Peters, Lederer, and Kelly (2012) highlight major court cases of online pornography that were determined to be labor or sex trafficking, like a 1999 “Rape Camp” website where viewers could make demands of sexually violent acts against Asian victims. In 2011, there was a case in Florida where two men would recruit women to be models, then drug, rape, and record videos of them without consent at their auditions to be shown and sold online. While not all cases of trafficking for pornography are this extreme, it is more common that fairly paid actors are pressured into performing new sexual acts by their agents and directors, which can quickly cross into sexual assault and trafficking (Peters, Lederer, & Kelly, 2012). Despite there being many adult film actors who are consenting and fairly paid, the danger is that there is no way for the viewer to know who did and did not fully and openly consent, therefore consumption of any online pornography is fueling the sex trafficking industry (Fight the New Drug, 2018). Additionally, with the consumers of violent forms of pornography, it is not only difficult to tell if the actors in the film agreed to the sexual acts, but also the consumers are continuously desensitized to the violence and may become consumers of trafficked persons to act out their fantasies (Luzwick, 2017; Peters, Lederer, & Kelly, 2012).

“Dancers at Love and Music bar, Angeles City” by Blemished Paradise is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

The Polaris Project (2017), using 10 years of data from calls, emails, and webforms sent to the National Human Trafficking Hotline, had 616 cases of sex trafficking through pornography, where most victims were U.S. citizens and women, and the non-consenting pornographic material was created by family members, intimate partners, and individual sex traffickers. There were also 78 reported cases of “Remote Interactive Sexual Acts” or commercial sex acts through webcams, phone sex chats, or texting lines. In the case of remote interactive sexual acts, the LGBTQ population was documented as 12% of the cases, which is odd considering usually the LGBTQ population makes up 2-3% of the exploited population in other cases of sex trafficking (Polaris, 2017).

A more recent variation of sex trafficking in relation to pornography is the idea of “revenge porn”. Revenge porn, or nonconsensual porn, is the threatened distribution, or actual distribution, of sexually explicit materials in order to control, blackmail, or shame a victim (The National Domestic Violence Hotline, 2016). Some victims willingly shared the materials initially with the recipient but did not consent to the additional distribution, while other victims are forced into making the materials by an individual who plans to use them as leverage for control (The National Domestic Violence Hotline, 2016). Revenge porn is a growing problem in the internet age, prompting some states to begin enacting legislation to criminalize the distributors (Kamal & Newman, 2016). While not yet widely considered a part of human trafficking, revenge porn utilizes force and coercion for the sexual exploitation of a victim. The long-term mental health effects of being a victim of revenge porn are similar to those of victims of child pornography, and include symptoms of depression, paranoia, guilt, and suicidal ideation (Kamal & Newman, 2016).

Pornography is not the only male entertainment industry involved in sex trafficking. While escorts, massage parlors, or health and beauty covers for prostitution are forms of male entertainment, they are covered more in forced prostitution. Strip clubs, bars, and cabanas, however, are a form of male entertainment that are not covered in forced prostitution. Victims trafficked in strip clubs, bars, and cantinas are often being sex and labor trafficked under the guise of male-focused restaurants and businesses (National Human Trafficking Hotline, n.d.c.; Polaris, 2017). The victims are forced to flirt with patrons and entice them into paying for more expensive products at the business, with the implicit or explicit agreement that sexual acts will be included (National Human Trafficking Hotline, n.d.C.; Polaris, 2017). From 2006-2017, there were 792 reports of trafficking in the United States fitting this description (Polaris, 2017).

Women being detained after a massage parlor was busted in a human trafficking ring.

https://lorrab.wordpress.com/2014/12/05/15-women-arrested-in-prostitutionhuman-trafficking-sting-at-brooklyn-massage-parlors/

Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking

Globally, children are common targets for sex trafficking recruitment. Yearly, traffickers exploit approximately one million children for the purpose of sex trafficking around the world (International Labor Organization, 2017). A conservative estimate of the number of children domestically involved in the sale of sex, pornography, escort services, stripping or other sexual acts is about 200,000 annually, with an estimated 244,000-325,000 additional children annually at risk (Goldberg & Moore, 2018). In 2018, 51.6% of criminal human trafficking cases were cases of sex trafficking of children (Currier & Feehs, 2019). The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (2018) estimates that 1 in every 7 missing children is likely a victim of sex trafficking. Reported cases of missing children are present in all 50 states.

The term Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking (DMST) was coined by Shared Hope International and is used to describe the commercial sexual exploitation (CSE) of American children on U.S. soil (Smith, Vardaman, & Snow, 2009). By virtue of being young, impulsive, and novelty seeking, children and adolescents are at an increased risk of being trafficked or sexually exploited (Smith, 2014). Additional risk factors for children becoming sex trafficking victims include: being runaways or homeless; being in foster care; prior abuse or neglect; substance abuse issues; poverty; missing or absent parents; difficulty in school; and being LGBTQ or other children who have been abandoned or ostracized by their family (The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, 2018; Shared Hope International, 2019; Smith, 2014). The three most common routes for the recruitment of children victims are social media, their local neighborhood, and clubs and bars (Shared Hope International, 2019). The average age a child is recruited into sex trafficking in the United States is 12-14 years old, but some children are exploited as toddlers and infants (Goldberg & Moore, 2018; Thorn, 2018). Similar to other sex trafficking victims, the exploiters of Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking victims can be peers, family members, significant others, or in some cases, strangers (Goldberg & Moore, 2018; Kotrla, 2010). Peers or perceived friends are reported to be the recruiters of individuals into minor sex trafficking in 44-68% of cases, with a peer being the actual trafficker in 28% of cases (Goldberg & Moore, 2018). While there are some instances where youth are approached and engaged in sexual acts one on one, in almost every case, a minor involved in DMST has a pimp (Smith, Vardaman, & Snow, 2009).

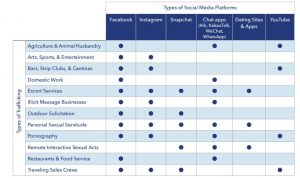

Not surprisingly, the internet and social media not only play a major role in the recruitment of Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking victims, but also in their sale (Goldberg & Moore, 2018; Kotrla, 2010). In 2018, 95% of teens reported having or having access to a smartphone, with 51% of teens using Facebook, 69% using Snapchat, 72% using Instagram, and 85% using YouTube (Anderson & Jiang, 2018). A report by Polaris (2017) reported all of these platforms, plus chat apps and dating apps are being used to recruit trafficking victims, as seen in the figure below. Traffickers use social media apps to find, build relationships with, and groom potential victims, and then use social media and the internet to advertise and sell their victims (Goldberg & Moore, 2018; Kotrla, 2010). Preying on the insecurities of teens, traffickers will build relationships, especially with young girls, telling them they are beautiful and mature, creating an insincere romantic relationship, promising gifts, or promising careers in modeling, acting, and dancing (Polaris, 2019a; Smith, 2014). In a study on Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking victims recruited since 2015, 55% of victims met their traffickers through social media, with 85% of the entire sample reporting that their trafficker spent a significant amount of time with them face-to-face building what seemed to be a meaningful relationship (Thorn, 2018).

Social media recruitment for human trafficking

Retrieved from The Polaris Project https://polarisproject.org/sites/default/files/Polaris-Typology-of-Modern-Slavery.pdf

Warning signs that a youth is engaged in DMST include but are not limited to: evidence of abuse, tattoos or branding, history of or recurring STIs, being withdrawn, asking for permission to speak or allowing another person to speak for them, having large amounts of money, and having expensive items with no way to pay for them such as electronics or designer clothes (Goldberg & Moore, 2010; The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, 2018). Smith, Vardaman, and Snow (2009) found misidentification of victims to be the primary barrier to rescuing minors who are being sex trafficked, and attributed misidentification to the frequent criminalization of victims. Williams (2018) would assert that this includes misidentification by the victim, law enforcement, the media and even the judicial system.

Interventions

The needs of sex trafficking victims span a number of disciplines that include medicine, law, and social work. Traffickers use drug addiction, access to housing and basic needs, physical abuse, criminal offenses, immigration-related tactics and blackmail to maintain control over their victims. Therefore, interventions must be able to break the dependence victims have on their traffickers. The first step in assisting sex trafficking victims is identification. Medical personnel in hospitals, emergency rooms, clinics, and shelters can act as first responders in identifying potential victims through knowing warning signs or red flags (Hodge, 2014). For DMST victims specifically, it is important for child protective service and child welfare workers, school officials and law enforcement officers to learn warning signs, have proper screening tools, and know what questions to ask (Meshelemiah, Poole, & Michel, 2013). This also applies to healthcare workers. Frontline workers in these arenas must put forth efforts to learn the warning signs, acquire screening tools, and familiarize themselves with protocol to intervene in instances of sex trafficking. These signs and red flags are detailed in Chapter 12: “Identifying Trafficking Victims in Healthcare Settings”. In the meantime, warning signs and red flags include behavioral cues like being fearful, anxious, depressed or submissive and show signs of drug use. Physical cues include poor hygiene and signs of physical abuse. Other indicators include not being free to speak or leave when they want to, having no control of one’s agency or money, having little to no possessions and being constantly monitored. Last, having no sense of person, place or time is a red flag when all or many of these elements interact with those previously listed (Polaris, 2019b).

After identification, ensuring access to resources that can provide basic needs like housing, food, and clothing is essential (Gezinski & Karandikar, 2013; Hodge, 2014). Knowing the availability of resources and programming as well as eligibility and documentation needed for said programming is an essential skill for those assisting sex trafficking survivors (Baldwin, 2003). Micro-practice therapeutic social workers and other mental health service providers will need to: help victims in addressing and living with their trauma; provide substance abuse counseling; and assist in developing victims’ coping skills to establish physical and psychological safety (Office for Victims of Crime Training and Technical Assistance Center, n.d.).

On a macro level, social workers should advocate for interagency collaboration, information sharing, specialized trainings, and coalition building to create streamlined community and large scale efforts to best serve trafficking victims (Clawson, Small, Go, & Myles, 2003). It is also important to increase awareness and understanding of the TVPA and trafficking in persons, develop protocols specifically for working with victims of trafficking, promote awareness and understanding for victims on their rights and legal protections, and expand outreach efforts (Clawson, et al., 2003). Shared Hope International (2019) specifically focuses on DMST and evaluates federal-and state-level legislation and policy efficacy and annual progress; social workers interested in policy work should undertake similar tasks to provide a social work lens on policy and legislation evaluation, implementation, and creation.

Quiz

Now, let’s shift gears and turn to a case study.

SARAH

Sarah is a 17-year-old girl living at home with her parents while she finishes high school. Sarah and her mother fight often, and her mother has people coming and going from their apartment several nights a week for drug transactions. One of the men starts talking to Sarah occasionally, telling her it’s not fair how her mom talks to her or treats her. Sarah begins thinking he understands her and cares about her point of view. After a few months of speaking occasionally, Sarah and the man, called Trip, begin texting. Trip tells her how she’s too pretty and smart to be single and not spoiled and begins buying her clothes, purses, and shoes and giving her money to treat herself. Sarah thinks that Trip genuinely cares about her and accepts the gifts, and spends time with Trip outside of when he comes to see her mom. Then, one day Trip tells Sarah he needs a favor because he is in a tight spot. He says he will come pick her up. After picking her up, Trip tells Sarah that he is running low on money and owes someone a lot. They have agreed that if they can spend some time with Sarah that they will cancel the debt. Since Sarah has received so much from Trip, she feels she owes it to him to “spend some time” with his friend. Trip takes Sarah to a motel and introduces her to his friend in one of the rooms. He then leaves and says he’ll be right back, he’s going to get something out of the car. While Trip is gone, the man threatens her and rapes her, telling her if she ever wants to leave the hotel room again she’ll comply. The man leaves shortly after he is finished with Sarah and she sees him talking to Trip in the parking lot before handing him a lot of money. When Trip comes back to the hotel room, Sarah asks what took him so long and tells him what happened. Trip tells her that if she expects to receive extravagant gifts she has to help him out sometimes, too. He says he’s sorry she is upset and it won’t happen again. Since Sarah believes that Trip cares about her, she believes him. However, it does happen again, and soon it happens more regularly. It takes Sarah over a year to realize that Trip does not care about her and is making money off her. At that point, however, Trip was the only person Sarah had consistently in her life and she felt like she brought it on herself. Sarah does not know how to leave Trip or who to turn to for help.

Real case study: https://sharedhope.org/2016/09/09/southwest-washington-girl/

Summary of Key Points

- Sex trafficking is the most common perception of human trafficking and affects millions of people around the world, with an estimated one million children being sex trafficked every year.

- Sex trafficking is not only forced prostitution, but it is a complex arena involving pornography, the male entertainment industry, escort services, massage and health parlors, and the buying and selling of children.

Supplemental Learning Materials

Websites

Globalslaveryindex.org

Traffickingmatters.com

Crimes Against Children Research Center: unh.edu/ccrc/prostitution/

FCASV.org

Demandabolition.org

Fightthenewdrug.org

Books

Half the Sky, Nicholas Kristof & Sheryl WuDunn

Girls Like Us, Rachel Lloyd

Invading the Darkness, Linda Smith

Articles

Center for Court Innovation. (n.d.). The Intersection of Domestic Violence, Sexual Assault, and Human Trafficking. Retrieved from https://www.courtinnovation.org/sites/default/files/documents/UnderstandingHumanTrafficking_2.pdf

Gewirtz-Meydan, A., Walsh, W., Wolak, J., & Finkelhor, D. (2018). The complex experience of child pornography survivors. Child Abuse & Neglect, 80, 238-248. DOI: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.03.031

O’hara, M. (2018). Making pimps and sex buyers visible: Recognising the commercial nexus in ‘child sexual exploitation’. Critical Social Policy, 39(1), 108-126. DOI: 10.1177/0261018318764758

References

Anderson, M. & Jiang, J. (2018). Report: Teens, Social Media & Technology 2018. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewinternet.org/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018/

Baldwin, M. (2003). Living in Longing: Prostitution, Trauma Recovery, and Public Assistance. Prostitution, Trafficking, and Traumatic Stress Ed: Melissa Farley. Routledge. New York, NY.

Clawson, H. Small, K., Go, E., & Myles, B. (2003). Needs Assessment for Service Providers and Trafficking Victims. Caliber Associates, Inc. Retrieved from https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/202469.pdf

Cody, H. (2017). Domestic Violence and Human Trafficking. UNICEF. Retrieved from https://www.unicefusa.org/stories/domestic-violence-and-human-trafficking/33601

Currier, A. & Feehs, K. (2018). 2018 Federal Human Trafficking Report. The Human Trafficking Institute. Retrieved from https://www.traffickingmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/2018-Federal-Human-Trafficking-Report-Low-Res.pdf

Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Resources: The Mindset of A Human Trafficking Victim. Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/orr/understanding_the_mindset_of_a_trafficking_victim_1.pdf

Farmand, R. (n.d.). Criminalization of Human Trafficking Victims. Wi-Her. Retrieved from http://www.wi-her.org/criminalization-of-human-trafficking-victims/

Fight the New Drug. (2018). An Online Epidemic: The Inseparable Link Between Porn & Trafficking (Infographic). Retrieved from https://fightthenewdrug.org/the-internet-can-be-a-very-unsexy-place-we/

Gezinski, L.B. & Karandikar, S. (2013). Exploring needs of sex workers from Kamathipura red-light area of Mumbai, India. Journal of Social Service Research, 39(4), 552-561. DOI: 10.1080/01488376.2013.794758

Goldberg, A. & Moore, J. (2018). Domestic minor sex trafficking. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of America, 27(1), 77-92. DOI: 10.1016/j.chc.2017.08.008

Grough, M. & Goldbach, T. (2010). Relationship Between Pimps and Prostitutes. Cornell University Law School Student Projects. Retrieved from https://courses2.cit.cornell.edu/sociallaw/student_projects/PimpsandProstitutes.htm

Hodge, D. (2014). Assisting victims of human trafficking: Strategies to facilitate identification, exit from trafficking, and the restoration of wellness. Social Work, 59(2), 111-118. DOI: 10.1093/sw/swu002

Hopper, E., & Hidalgo, J. (2006). Invisible chains: Psychological coercion of human trafficking victims. Intercultural Human Rights Law Review, 1, 185-210. Retrieved from https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/ichuman1&i=198

International Labor Organization. (2017). Global Estimates of Modern Slavery. Geneva. Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—dcomm/documents/publication/wcms_575479.pdf

Kamal, M., & Newman, W. (2016). Revenge pornography: Mental health implications and related legislation. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry Law, 44, 359-367. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/9283/a01263d26c34dfe2f7943ee18ea311a4a8da.pdf

Kotrla, K. (2010). Domestic minor sex trafficking in the United States. Social Work, 55(2), 181-187. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/dcd1/adff7da96a9363e80854a77cc2d54652ee8d.pdf

Lillie, M. (2014). Human Trafficking: Not All Black and White. Human Trafficking Search. Retrieved from https://humantraffickingsearch.org/human-trafficking-not-all-black-or-white/

Luzwick, A. (2017). Human trafficking and pornography: Using the Trafficking Victims Protection Act to prosecute trafficking for the production of internet pornography. Northwestern University Law Review, 111, 137-153. Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/orr/understanding_the_mindset_of_a_trafficking_victim_1.pdf

Meshelemiah, J.C.A. & Lynch, R.E. (2019). Sex Trafficking: The Intersection of Race, Drugs, “Dope Boys” – and Emergent Leaders. (Presentation). The Kirwan Institute, Columbus, OH.

Meshelemiah, J.C.A., Poole, A., & Michel, E. (2013). Creating a standard protocol for domestic minor sex trafficking victims: How child welfare workers can better facilitate better protections under the guise of the TVPA. (NASW). Specialty Practice Sections. Children, Adolescents, Youth and Family Section Connection. (Winter). Retrieved from https://www.socialworkers.org/assets/secured/documents/practice/cayawinter2013.pdf

Monto, M. & Milrod, C. (2014). Ordinary or peculiar men? Comparing the customers of prostitutes with a nationally representative sample of men. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 58(7), 802-820. DOI: 10.1177/0306624X13480487

Morel, P. (Director). (2008). Taken. United States: EuropaCorp.

National Human Trafficking Hotline. (n.d.a.). The Victims. Retrieved from https://humantraffickinghotline.org/what-human-trafficking/human-trafficking/victims

National Human Trafficking Hotline. (n.d.b.). The Traffickers. Retrieved from https://humantraffickinghotline.org/what-human-trafficking/human-trafficking/traffickers

National Human Trafficking Hotline. (n.d.c.). Hostess/Strip Club Based. Retrieved from https://humantraffickinghotline.org/sex-trafficking-venuesindustries/hostessstrip-club-based

National Human Trafficking Hotline. (2017). Hotline Statistics: View Stats by State. Retrieved from https://humantraffickinghotline.org/states

O’Day, C. (2018). How Global Sporting Events Can Encourage Human Trafficking. InterAction. Retrieved from https://www.interaction.org/blog/how-global-sporting-events-can-encourage-human-trafficking/

Office for Victims of Crime Training and Technical Assistance Center. (n.d.) Mental Health Needs. Office of Justice Programs. Retrieved from https://www.ovcttac.gov/taskforceguide/eguide/4-supporting-victims/44-comprehensive-victim-services/mental-health-needs/

Ohio Justice & Policy Center. (n.d.). Justice, Recovery, and Reentry for Victims of Human Trafficking. Retrieved from http://ohiojpc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/HT-Victim-Barriers-Handout-v2.pdf

Peters, R., Lederer, L., & Kelly, S. (2012). The slave and the porn star: Sexual trafficking and pornography. The Protection Project Journal of Human Rights and Civil Society, 5, 1-22. Retrieved from https://www.rescuefreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/slave-and-the-porn-star.pdf

Polaris. (2019a). Blog: Looking for love online this Valentine’s Day?. Retrieved from https://polarisproject.org/blog/2019/02/07/looking-love-online-valentines-day

Polaris. (2019b). Recognize the signs. Retrieved from https://polarisproject.org/human-trafficking/recognize-signs

Polaris. (2017). The Typology of Modern Slavery: Defining Sex and Labor Trafficking in the United States. Retrieved from https://polarisproject.org/sites/default/files/Polaris-Typology-of-Modern-Slavery.pdf

Reed, S., Kennedy, M., Decker, M., & Cimino, A. (2019). Friends, family, and boyfriends: An analysis of relationship pathways into commercial sexual exploitation. Child Abuse & Neglect, 90, pg 1-12. DOI: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.01.016San Francisco Human Rights Commission. (n.d.) What is Human Trafficking? Retrieved from https://sf-hrc.org/what-human-trafficking

Shared Hope International. (2019). Home. Retrieved from https://sharedhope.org/

Smith, H. A. (2014). Walking Prey: How America’s Youth Are Vulnerable to Sex Slavery. Palgrave MacMillan. New York, NY.

Smith, L., Vardaman, S., & Snow, M. (2009). The National Report on Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking America’s Prostituted Children. Shared Hope International. Retrieved from http://sharedhope.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/SHI_National_Report_on_DMST_2009.pdf

Stark, C. & Hodgson, C. (2003). Sister Oppressions: A Comparison of Wife Battering and Prostitution. Prostitution, Trafficking, and Traumatic Stress Ed: Melissa Farley. Routledge. New York, NY.

The National Domestic Violence Hotline. (2016). Behind the Screens: Revenge Porn. Retrieved from https://www.thehotline.org/2016/01/14/revenge-porn/

The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. (2018). The Issues: Child Sex Trafficking. Retrieved from http://www.missingkids.com/theissues/trafficking

Thorn. (2018). Survivor Insights: The Role of Technology in Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking. Retrieved from https://www.thorn.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Thorn_Survivor_Insights_061118.pdf

Trafficking Victims Protection Act. (2000). H.R. 3244, Pub. L. No. 106-386.

United Nations. (2003). Protocol to prevent, suppress, and punish trafficking in persons. (Resolution 55/25). Retrieved from https://www.unodc.org/documents/treaties/UNTOC/Publications/TOC%20Convention/TOCebook-e.pdf

United Nations. (2018). Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 2018. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Retrieved from https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/glotip/2018/GLOTiP_2018_BOOK_web_small.pdf

U.S. Department of State. (2018). Trafficking in Persons Report June 2018. Retrieved from https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/282798.pdf

Williamson, C. (2108, May 25). Celia Williamson: Language is important, and so is logic. The Blade. Retrieved from https://www.toledoblade.com/Op-Ed-Columns/2018/05/25/Celia-Williamson-Language-is-important-and-so-is-logic.html