Chapter 5: The Weaponization of Drugs

ABSTRACT

Drug use among sex trafficked victims is common and is used in a variety of ways in the sex trafficking arena. Drugs are used to: induce compliance; create dependency; feed a “habit”; punish an unwilling victim; cope with the stress of sex trafficking; lure in a vulnerable and unsuspecting individual; criminalize a victim; and incapacitate a victim. In essence, they are weaponized in the trafficking arena. This chapter will discuss how drugs are used as weapons.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, the student will be able to:

- Define substance use

- Understand the symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Key Words: Substance Use Disorders, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

GLOSSARY

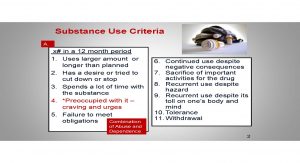

Substance Use Disorders: A cluster of behavioral, cognitive and physiological symptoms that result from the persistent use of a substance (e.g., a drug or toxin) despite its negative consequences

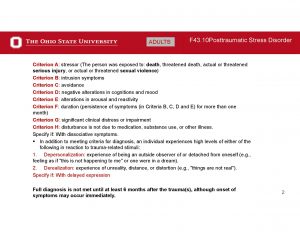

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: The development of a cluster of symptoms following exposure to one or more traumatic events

Substance Use and Sex Trafficking of Adults

According to Hughes (as cited in Reichert & Sylwestrzak, 2013), more than 70% of trafficking victims surveyed reported using substances. Many meet the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5) of Mental Disorders clinical criteria for substance use disorders as described in the table below. In the human trafficking arena, drugs are used for multiple purposes and in a variety of ways. Traffickers use drugs to lure in persons with an established drug use problem, which is reported to be a small number of victims. They also use drugs to entice or lure in an inexperienced victim to get her “hooked”. Later, drugs are often used as a reward (for compliance) and as a punishment for the drug dependent victim. The trafficker also sometimes forces the consumption of addictive substances because it will guarantee to the trafficker that: 1) the victim will become dependent; 2) drug dependencies will make the victim incur debt to the trafficker; 3) the trafficker will be able to control the victim through drug use; and 4) the victim may become unduly influenced to stay due to trauma bonding despite how bad the trafficking experience may be (Bernat & Winkfeller, 2010; Kara, 2009; Meshelemiah, Gilson & Prasanga, 2018; Williamson, Dutch & Clawson, 2007). Drugs are also used to incapacitate the client so that she conforms to the demands of the trafficker. In this chapter, the authors discuss drug use among domestic and foreign national sex trafficking women survivors.

Cumulatively, drugs are used to control the victim and to create dependency on the perpetrator once dependency on the drug is established (Becky Owens Bullard Consulting, 2012). It is also believed that some trafficking victims may resort to drug use to help cope with the victimization (Latin American and Caribbean Health Network, 2003; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014). Foreign victims, for example, who have been sex trafficked have reported: 1) being required to have daily sex with men in the double digits; 2) having to meet a daily money quota; and 3) having to have sex without condoms, which puts them at greater risk for HIV, Herpes Simplex Virus-2 (HSV-2), and other sexually transmitted infections (STI) (Derseh, Wasie, & Edris, 2012; Kara, 2009). In addition to these demands, sex trafficking victims are subjected to constant threats and complete isolation (U.S. Department of State, 2014).

According to Meshelemiah, Gilson and Prasanga (2018), drugs are sometimes deliberately entered into the equation—again, for the purposes of compliance, incapacitation, and dependency/addiction. The researchers argue, however, that there are still more reasons for why traffickers utilize drugs with trafficking victims. In some cases, the trafficker’s motivation for drug use may be to set up the trafficking victim in case she is ever arrested on prostitution and/or prostitution-related charges. If apprehended by law enforcement while under the influence or in possession, drug using victims may lose their credibility and presumed innocence. The trafficker knows that her arrest will distract from her victimization.

When a sex trafficked victim uses a drug and subsequently develops a dependence, it further increases her vulnerability. Increased vulnerability and drug dependence are integral tools used by the trafficker to get what he wants— more “work” from a person who is viewed as property and as a commodity. In the case of foreign nationals, women with confiscated passports/identification cards, undocumented statuses, language barriers, and are long distances from their biological families are at great risk for increased exploitation (Kara, 2009; Sigmon, 2008). These factors, coupled with instilled fear, lack of knowledge of the law and her rights, and fear of law enforcement, make the victim susceptible to the harshest of conditions (Sigmon, 2008).

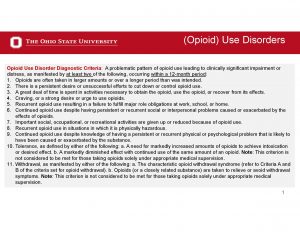

In the case of sex trafficked women as a whole, drugs are used like weapons—they are used as a tool for mass destruction; as a tool to gain advantage over an already vulnerable victim; and as a tool to disarm a victim due to its power. Drugs are weaponized in the sex trafficking world. Commonly used drugs with sex trafficking victims include tobacco, alcohol, hallucinogens, cocaine, heroin, sedatives, and marijuana (Kara, 20009; McGaha, 2011; Raymond & Hughes, 2001; Williams et al., 2013). Heroin, which is an opioid, is particularly addictive (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). Heroin and other opioids are frequently used drugs by trafficking victims (Office on Trafficking in Persons of the Administration of Children and Families, “n.d.”). As seen in the slide on Opioid Use Disorders, impairment and distress can take place in a number of areas that include the cognitive, behavioral and physiological (APA, 2013).

The emotional consequences of forced prostitution among sex trafficked victims can be extreme and sometimes more severe than the physical consequences (Raymond & Hughes, 2001). Specific to these authors’ basic premise here, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Program (SAMHSA) based services are critical to the trafficking survivor. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) is a branch of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. It has the responsibility of improving the quality and availability of services to those who suffer from substance use and mental disorders (SAMHSA, 2014a). SAMHSA’s mission and goal is to protect and promote the human, civil, and legal rights and moral freedoms of those served through its activities (De Jong & Reatiq, 1998).

Many sex trafficked victims suffer from disorders that fall under the auspice of the SAMHSA administration. For example, many sex trafficking victims suffer from substance use disorders along with depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, dissociative disorders, borderline personality disorder, eating disorders, and suicide attempts (Farley, 2010; Raymond & Hughes, 2001; Sigmon, 2008; Williamson, Dutch & Clawson, 2007). According to the most current version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) of Mental Disorders, trafficking victims are especially at high risk for developing Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (APA, 2013).

SAMHSA’s working definition of trauma purports that it involves an event, a series of events, or a set of circumstances that the individual experiences in a physically or emotionally harmful or threatening way. One’s response to the events then results in long lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and overall psychosocial and spiritual well-being. Trauma is considered to be a combination of the event, the experience, and the effect (SAMHSA, 2014b). Consistent with the previously stated disorders, Raymond and Hughes (2001) report that many survivors report numbness, depression, lethargy, self-blame/guilt, poor concentration, loss of appetite, and sleep disturbances. The American Psychiatric Association shows that trauma is oftentimes co-morbid with substance misuse and other DSM disorders (APA, 2013).

*Social Determinants of Health

An important layer to add to the discussion on human trafficking is the social determinants of health framework. According to this framework, extenuating circumstances contribute to one’s position, environment, and opportunities in life. These factors, when compromised, preemptively undermine a person’s potential by leading them to fall into situations of vulnerability and/or danger. As outlined in a joint report by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Commission on Social Determinants of Health, a person’s access to healthcare, education, and adequate housing, along with work conditions and the immediate environment, all affect one’s outcomes (WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health & World Health Organization, 2008).

While there is a large variance in health factors between countries, often determining life outcomes by region, it is the inequality of social determinants specifically within the same areas (varying on an individual level) that creates great divides and proves health to be an outcome impacted by various social factors (Navarro, 2009). From a public health perspective, these social determinants of health can lead to the development of risky behaviors and increased exposure to harmful outcomes such as human trafficking.

At its most basic level, the premise of a human right is that every individual in the world is entitled to it. Safety, security, and freedom are all standard human rights, but they can be compromised in environments where unequal social determinants of health leave some populations/groups more at risk than others. For human trafficking victims surrounded by multiple social determinants which breed insecurity and enable manipulation (such as food and job insecurity, unstable housing and limited access to healthcare and other support systems), the chances of force, fraud, and coercion are heightened (Perry & McEwing, 2013). In their systematic review with a specific focus on Southeast Asia, Perry and McEwing (2013) point out that social determinants, including citizenship, level of education, and gender,were found to be compromised in populations of foreign national human trafficking victims.

As sex trafficking is examined among foreign nationals in this context, it is juxtaposed that basic needs are unmet in the country of origin (Jones, Engstrom, Hilliard & Diaz, 2007; Okogbule, 2013). As victims become trafficked, their needs are further denied, beyond their compromised determinants of health. This is especially exacerbated among those who develop substance use issues. Upon exit from trafficking, victims will commonly experience unstructured freedom and (for some) an untreated drug problem in a foreign country without proper support and services. As pointed out by Zimmerman et al. (2008) in an extensive study conducted to understand the health needs of victims post-trafficking in Europe, the trauma experienced by trafficking victims often leads to an inability to judge one’s environment and to understand what is safe. This instability only perpetuates vulnerability to trafficking, manipulation, and further suffering—disconcertingly mirroring the beginning of their journey, in which compromised determinants of health created disadvantage in the first place. Thus, human rights violations are the cause and consequence of human trafficking.

In order to combat this phenomenon, it is important to strategically approach human trafficking as an issue initiated and perpetuated by the unequal determinants which create outcomes contradictive of the rights that people share as human beings. By taking an approach informed by the role that social determinants play, one can more holistically understand the circumstances upon which victims’ experiences are established, and continue with a mindset more attentively focused on creating equitable approaches to survivors and their needs post-trafficking.

*Written by Jacquelyn Meshelemiah and Carra Gilson (Master of Public Health Student)

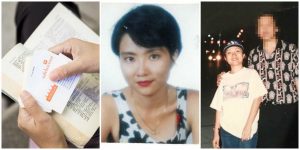

SHANDRA WOWORUNTU

The following is the true story of a foreign national victim named Shandra Woworuntu. Her story is a common trajectory of a foreign national victim of sex trafficking. This case illustrates the journey of a woman traveling to a foreign country for a better opportunity only to be lured and trapped into trafficking and drug use (Woworuntu, 2016).

In 2001, Shandra was a recently unemployed 24-year-old-woman from Indonesia. She had a 4-year degree and a 3-year-old daughter to provide for. She arrived to the United States in pursuit of a job in a hotel. Upon landing at the JFK Airport, she was led to a car by a man under the impression that he was taking her to her place of employment. After being shuffled between three different vehicles and across various stopping points throughout New York, she realized that something was wrong. By the end of her first night on U.S. soil, Shandra was forced into having sex with a man she did not know, thus beginning her traumatic journey as a victim of human trafficking.

The use of manipulation, both physically and mentally, pervaded the months in which Shandra was trafficked. Her traffickers forced her to have sex with lots of men. Shandra explains that on the first occasion her trafficker told her, “It won’t happen again”, as he rubbed her back. Initially, after this reassuring encounter, Shandra asserts, “I trusted him”, but this manipulative behavior, combined with fear tactics effectively kept Shandra (and the other women whom she was enslaved with) in submission. Having witnessed an act of violence against another woman early on, Shandra knew that she had to do what was told of her. In addition to acts of physical and sexual violence, and triggering mental distress, the traffickers induced passivity in Shandra and the other women through forced drug use. “The traffickers made me take drugs at gunpoint…maybe it helped make it all bearable”, she shared in recollection of her trauma.

While Shandra quickly recognized that her situation was compromising and unsolicited, a physical dependency on drugs (in addition to other forms of coercion to which she was being subjected to) kept her entrapped. The experience quickly induced emotional trauma. She explains, “…it was like I was numb, unable to cry. Overwhelmed with sadness, anger, disappointment, I just went through the motions, doing what I was told and trying hard to survive”. The traffickers were forceful and ceaseless in their treatment of Shandra, as they worked to keep her in a compromised state. Drug use and abuse continued to be the tactic relied upon to create submission and dependence. Shandra remembers, “I was often high on drugs”. Despite these horrifying conditions and traumatic treatment, Shandra was able to successfully escape on her third attempt.

Left to Right: Business cards from groups that helped Shandra; Shandra’s 2001 application photo; Shandra with her trafficker. https://www.safehorizon.org/tag/shandra-woworuntu/

Shandra’s story highlights vulnerability, forced drug use, mental anguish, violence, and sexual assaults associated with human trafficking. It also depicts the push and pull factors of trafficking. Push factors relate to those variables that make one vulnerable to being deceived and manipulated into a trafficking situation. This includes being impoverished; having few supports; being homeless; having a lack of knowledge; having few employment opportunities; and being subjected to gender stereotypes, for example. Pull factors relate to those variables that draw in victims to a potential harmful situation. This includes looking for a potential marriage; gainful employment; housing; and other material gains (International Labor Organization (ILO), 2011; Krehbiel, 2016; Okech, Morreau, & Benson, 2011; Wooditch, 2011). More importantly, it reiterates the importance of supporting sex trafficking victims and survivors through access to substance use treatment and mental health services, in order to redress the detrimental effects that human trafficking has on one’s mental and physical health outcomes as shown in Shandra’s story.

Quiz

Now, let’s shift gears and turn to a case study.

Summary of Key Points

- Drug use is common in the sex trafficking arena.

- Drugs are used to: induce compliance, create dependency, feed a “habit”, punish an unwilling victim, cope with the stress of sex trafficking, lure in a vulnerable individual, criminalize a victim and incapacitate a victim.

Supplemental Learning Materials

Shandra Woruntu Full Story 2018. Video (7:35 minutes)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EGpcM_bxdh4

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Becky Owens Bullard Counseling. (2012). Human trafficking intersections with drug endangered children. Issue Brief. Retrieved from www.beckyowensbullard.com

Bernat, F.P., & Winkeller, H.C. (2010). Human sex trafficking: The global becomes local. Women & Criminal Justice, 20, 186-192.

De Jong, J. & Reatiq, N. (1998). SAMHSA philosophy and statement on ethical principles. Ethical Behavioral Journal, 8(4), 339-343.

Derseh, L., Wasie,B., & Edris, M. (2012). Unsafe sexual practice among cross-border commercial sex workers in Mettema Yohannis, Northwest Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Health Biomedical Science, 5(1), 11-20.

Farley, M. (Ed.). (2010). Prostitution, trafficking, and traumatic stress. New York: Routledge.

International Labor Organization. (2011). Trafficking in persons overseas for labor purposes: The case of Ethiopian domestic workers. ILO Country Office: Addis Ababa.

Jones, L., Engstrom, D.W., Hilliard, T., & Diaz, M. (2007). Globalization and human trafficking. Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, 34(2), 107-122.

Kara, S. (2009). Sex trafficking: Inside the business of modern slavery. New York: Columbia University Press.

Krehbiel, S. (February 24, 2016). The victim narrative on sex-trafficking: An interview with Yvonne Zimmerman (Part 1). Our untold stories: World Press.

Latin American and Caribbean Health Network. (2003). The trafficking of women: A human rights issue. Women’s Health Journal, 2, 19-21.

McGaha, J. (2011). An integrated approach to anti-human trafficking task force development in Eastern Europe. National Science Science Journal, 36(2), 87-93.

Meshelemiah, J.C.A., Gilson, C., & Prasanga, A.P.A. (2018). Use of drug dependency to entrap and control victims of human trafficking: A call for a US federal human rights response. Dignity: A Journal on Sexual Exploitation and Violence, 3(3), Article 8.

Navarro, V. (2009). Social determinants of health: What we mean by social determinants of health. International Journal of Health Services, 39(3), 423-441.

Office on Trafficking in Persons of the Administration of Children and Families. (nd). Retrieved from https://www.google.com/search?q=opioids+used+by+sex+trafficked+persons&rlz=1C1GCEU_enUS820US820&oq=opioids+used+by+sex+trafficked+persons&aqs=chrome..69i57.11901j1j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8

Okech, D., Morreau, W., & Benson, K. (2011). Human trafficking: Improving victim identification and service provision. International Social Work, 55(4), 488-503.

Okogbule, N.S. (2013). Combating the “new slavery” in Nigeria: An appraisal of legal and policy responses to human trafficking. Journal of African Law, 57(1), 57-80.

Perry, M., & McEwing, L. (2013). How do social determinants affect human trafficking in Southeast Asia, and what can we do about it? A systematic review. Health and Human Rights, 15(2), 138-159.

Raymond, J.G., & Hughes, D.M. (2001). Sex trafficking of women in the United States: International and domestic trends. Retrieved from http://bibliobase.sermais.pt:8008/BiblioNET/upload/PDF3/01913_sex_traff_us.pdf

SAMHSA. (2014a). About us. Retrieved from http://beta.samhsa.gov/about-us

SAMHSA. (2014b). Trauma definition. Retrieved from http://www.samhsa.gov/traumajustice/traumadefinition/definition.aspx

Sigmon, J.N. (2008). Combatting modern-day slavery: Issues in identifying and assisting victims of human trafficking worldwide. Victims and Offenders, 3, 245-257.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2014). Resources: Common health issues seen in victims of human trafficking. Retrieved from http://www.justice.gov/usao/ian/htrt/health_problems.pdf

WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health, & World Health Organization. (2008). Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health: Commission on social determinants of health final report. International Government Publication. Retrieved from http://osu.worldcat.org/oclc/248038286

Williamson, E., Dutch, N.M., & Clawson, H.J. (2007). Evidence-based mental health treatment for victims of human trafficking. Retrieved from http://aspe.hhs.gov/hsp/07/humantrafficking/mentalhealth/index.pdfWooditch, A. (2011). The efficacy of the Trafficking in Persons report: A review of evidence. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 22(4), 471-493.

Woworuntu, S. (March 30, 2016). My life as a sex trafficking victim. Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-35846207

Zimmerman, C., Hossain, M., Yun, K., Gajdadziev, V., Guzun, N., Tchomarova, M., …Watts, C. (2008). The health of trafficked women: A survey of women entering post trafficking services in Europe. American Journal of Public Health, 98(1), 55-59.