Chapter 6: Labor Trafficking and Supply Chain Transparency

ABSTRACT

According to the International Labor Organization, labor trafficking is a high-profit, low-risk criminal enterprise that entraps millions of people around the world into horrendous working conditions. Although individual perpetrators are common, so are businesses that do not prevent trafficking from taking place in their supply chains. Consumers, however, can play a role in fighting trafficking by conscious consumerism. This chapter discusses labor trafficking and conscious consumerism.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, the student will be able to:

- Define labor trafficking

- Understand supply chains

- Become a conscious consumer

Key Words: Labor Trafficking, Debt Bondage or Peonage, Slavery, Fraud, Coercion, Smuggling

GLOSSARY

Labor Trafficking: The recruitment, transportation, transfer, habouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or of receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation

Debt Bondage or Peonage: Occurs when traffickers demand labor of the victim as a means of repayment for a real or alleged debt. The offenders do not reasonably apply a victim’s wages toward the payment of the debt. Another strategy of the offender is to limit or define the type and length of the debtor’s services. The victims may actually be charged fees by the traffickers, such as money for transportation, rooms, food, incidentals, interest, fines, and other charges such as those for “bad behavior”. Wages may be withheld or excessively reduced that even violate previously made agreements. Debt bondage ensnares a victim in a debt cycle that he or she can never pay down.

Slavery:The condition of being under the control of another person, in which violence or the threat of violence, whether physical or mental, prevents a person from exercising her/his freedom of movement or free will Indentured Servitude: The condition in which an individual enters into a contractual agreement, freely or otherwise, binding him/her to work for an employer for a fixed term in order to repay a debt Force: Includes the use of physical restraint or causing severe physical harm; physical violence such as rape, assault, and restriction of movement or physical confinement is often used as a way to control victims

Fraud: Can involve promises which are not truthful, usually regarding employment, wages, working conditions, or other subjects; for example—persons may be promised a high paying position in another country, but when they arrive they find themselves manipulated into forced labor

Coercion: Includes threats of serious harm to or physical restraint against the victim. A scheme, plan, or pattern intended to cause the victim to believe that failure to perform an act would result in severe harm to or physical restraint against that person. It also encompasses the actual or threatened abuse of the legal process.

Smuggling:Although there is a connection to human trafficking, human smuggling is another issue. Smuggling is the illegal transport of a person across a country’s border, and is transnational. With smuggling, individuals consent to being smuggled. Rather than a crime against a particular individual, this is a crime that is committed against a country. Criminals take advantage of the desperation and humanitarian crises for financial gain. Human smuggling may result in trafficking, but are considered two separate crimes

Sources

AMN Healthcare Education Services. (2018, March 25). Human Trafficking: Implications for Health Care Professionals. Retrieved from https://lms.rn.com/getpdf.php/2227.pdf

Human Trafficking Center. (2019). Definitions/Taxonomy Database. Retrieved from https://humantraffickingcenter.org/problem/database/

Labor Trafficking: Food for Thought

Unlike the previous chapters, this chapter is set up a little differently. It starts with a commentary from one of the authors and then moves on to labor trafficking facts, supply chains, and conscious consumerism.

COMMENTARY ON LABOR TRAFFICKING AND CONSUMERISM:

WAKE UP!!

As so eloquently stated by Fannie Lou Hamer, an American voting and women’s rights activist, community organizer, and a leader in the civil rights movement, “I am sick and tired of being sick and tired!” I am sick and tired of meeting children in Ghana who work long hours on cocoa plantations, but do not attend school or even get to taste chocolate themselves. I am sick and tired of seeing Coco-Cola products throughout many rural areas in Africa but see no economic prosperity in that same region. I am sick and tired of getting emails from Immokalee activists about the tomato pickers in Florida who laboriously tote 50-pound loads on their shoulders each and every day but cannot convince many owners of major grocery stores and restaurant chains to simply pay the workers one more penny per pound. I am sick and tired of seeing immigrants treated like bottom feeders in countries they migrate to—like the Nicaraguans in Costa Rica and the Mexicans in America who are relegated to the slums or ghettos and/or the worst jobs available. I am sick and tired of seeing children being forced to beg in Ghana, Uganda, and Mexico. I am still horrified by the long-haired, shoeless child from Niger who grabbed my hand in Accra, Ghana, and wouldn’t let go until I gave him or her money. To this day, I still don’t know if the child was a girl or a boy because he or she was so browned with dirt from head to toe that gender detection was not a possibility. Last, I am sick and tired of reading these three words—“Made in China”. Aren’t people curious as to why, and better yet, how so many products sold around the world—not just in the U.S.—are made in China? Do we think that all of these products can be made at the low prices that we purchase them at by adults working 9 to 5, five days a week at a living wage? I know that there are 1.3 billion people in China—and that’s a lot of people—but are you serious? Please do the math! The numbers simply do not add up for the rate and volume of mass production of the millions of products we love, enjoy, and consume…unless you factor in slavery, forced labor, and child labor. Folks, if prices are too good to be true, they are too good to be true. I know what you are thinking, “She has it all wrong. Those people are happy to have those jobs! A dollar is a lot of money over there!” Or better yet, you are probably saying, “If I stop shopping, the economic structure of the entire country will collapse because I singlehandedly keep Michael Jordan rich; keep iPhone revenues in the billions; keep the diamond industry executives smiling at the end of each quarter; and I keep Walmart as the mega-business to chase.” Wait, Mr. and Ms. Money Burns My Pocket, let me assure you that if you become a more conscious consumer, the World Bank will not collapse and in the famous words of Celine Dion, [your] heart will go on, and so will the Dow Jones numbers in New York City.

The authors are going to focus on labor trafficking for the purposes of merchandised goods in this chapter because it is something that we are all complicit in as consumers. It is also something that we all can do something about. Let me tell what I mean by that statement. Suppliers of material goods bank on a few things: ignorant shoppers, unconscious shoppers, bargain shoppers, gluttonous shoppers, and shoppers in a hurry to get what they want in the most convenient way possible by any means necessary no matter how it is made, who made it, and under what conditions. Which one of these (or all) best describes you? It’s a good chance I have just described just about every shopper in the Western world.

As much as I hate to say it, retailers just hit the nail right on the head. They know each and every one of us personally. They do greet us by name when they send us emails and text messages, right? Well, maybe they don’t know us personally and only know our names because we would have given it to them during a previous shopping excursion. Maybe they are simply mind readers, eh? On the other hand, they do not need a sixth sense or have to break any telecommunication laws to know us—we will tell them all of our innermost secrets and deepest desires if only they ask. Think about it, those little surveys we are constantly asked to complete after we make a purchase (to be eligible to be put in a drawing for a $25 gift card) are not really designed to increase customer satisfaction; they are really designed to assess what it will take to bring our gluttonous urges to an all-time high, thereby resulting in an emergency shopping spree or, as some would say, retail therapy. Aren’t you even a little curious as to why store clerks ask for your telephone number and email address during routine purchases? Are they for warranty purposes? To cut down on the use of paper by emailing receipts? No, I don’t think so—at least not for the primary reason for requesting these data. They simply want our contact information so that they can entice us into spending more money with them. You do know that retailers are separatists, don’t you?—They believe in separating you from your money. Well, the Bible teaches me that a fool and his or her money will soon part. Oh yeah, that’s the last thing that retailers bank on—they bank on the possibility that we are all fools.

After I teach a course or present on human trafficking anywhere in the world, I am always asked, “What can I do?” Well, this is what you can do. You can read this chapter. Tell all of your friends to read this book. Tell your family members to read this book. Just tell everyone to read this book. This book will help guide you (and all of them) in becoming a more conscious consumer. Basically, I am going to tell you to do your homework before you buy a diamond (or maybe encourage you to buy a lab-created diamond in its place). I am also going to tell you to think about everything you eat, every pair of sneakers you purchase, every label you put on your body, and every electronic you intend to buy. Basically, I am going to challenge you to take the time to question the origin of your goods. We all must wake up and do something! James Keady (an activist, former athlete, former coach, politician) said it best when he said, “You have tremendous power [as a consumer].” I agree completely. Let’s use what we have for the greater good of a global society.

Dr. Jacquelyn Meshelemiah

Let’s start…How Many Slaves Do You Own?

After taking this “survey”, how many slaves do you earn? 100? 45? 25? 10? Unless you are committed to living a minimalist lifestyle, you are probably feeling very surprised by how your impulsive, extravagant, or excessive shopping contributes to slave labor (at some stage in the supply chain). Well, now that you know this, what do you plan to do about it?

Labor Trafficking

Labor traffickers include a wide range of perpetrators who use force, fraud, violence, threats, lies, coercion, torture, sexual abuse/rape, intimidation, attempted murder, confiscation of identity documents and debt bondage to ensnare their victims into trafficked scenarios. These varied perpetrators include:

- Recruiters,

- Contractors,

- Employers,

- Brothel and fake massage business owners and managers,

- Employers of domestic servants,

- Gangs and criminal networks,

- Growers and crew leaders in agriculture,

- Intimate partners,

- Family members,

- Labor brokers,

- Factory owners and corporations,

- Pimps, and

- Small business owners and managers.

(National Human Trafficking Hotline, n.d.; NIJ, 2016; Polaris, 2019)

In a study by the National Institute of Justice (2016), the researchers found that 66% of traffickers were male; most were in their 30s and 40s; and approximately 50% were U.S. citizens. In the agriculture industry, 82% of suspected traffickers were U.S. citizens, while suspected traffickers in the hospitality, restaurant, and domestic servitude cases were mainly non-citizens.

Victims of labor trafficking include a diverse group of vulnerable persons who are in high debt, impoverished, homeless, orphaned, seeking high paying jobs, seeking love/marriage, wanting an education or to travel, and/or who are undocumented, and lack strong labor protections. They include people in the United States and all over the world who are:

- Women,

- Men, and

- Children.

Contrary to popular beliefs, labor trafficking occurs in the United States—not just in developing countries around the world. Domestically, labor trafficking takes place in the form of domestic servants, farmworkers, factory workers, door-to-door sales crews, restaurants, construction sites, carnivals, nail salons, and massage parlors (National Human Trafficking Hotline, n.d.; Polaris, 2019). In a study by the National Institute of Justice (2016), the researchers found that 71% of trafficked persons in their foreign national sample entered into the United States legally on H-2A visas (agriculture purposes) and H-2B visas (hospitality, construction, and restaurants purposes), while trafficked persons who entered into the U.S. illegally, were mostly found in agriculture and domestic work. Additionally, trafficked persons mainly escaped on their own and did not receive specialized services until months later.

Businesses or Services that Traffickers Exploit

Not only do traffickers exploit men, women, and children, but they also exploit businesses and services. The following are examples of just some of the businesses and services that traffickers take advantage of:

- Advertising (online and print),

- Airlines, bus, rail, and taxi companies,

- Financial institutions, money transfer services, and informal cash transfer services,

- Hospitality industry, including hotels and motels,

- Labor brokers, recruitment agencies, or independent recruiters,

- Landlords, and

- Travel and visa/passport services.

(National Human Trafficking Hotline, n.d.)

Given this reality, it is critical that all persons employed in these businesses and service areas be properly trained to identify trafficking victims, know who to contact in suspected cases of human trafficking, and care enough to act when known trafficking activities are uncovered. How to identify trafficking victims is discussed in detail in Chapter 12: “Identifying Trafficking Victims in Healthcare Settings”. In the meantime, the following are important indicators for you to be familiar with. They are related to atypical conditions, unusual behavioral signs, physical signs of abuse/neglect, loss of control, etc.

The Tea Industry

Let’s talk about tea. Do you drink tea? If so, do you drink it hot, cold, or both ways? Do you ever think about how tea is made or which countries primarily produce it? Do you ever think about the supply chain involved in tea? Well, take a moment to read more about the many countries who are guilty of human rights violations throughout the supply chain of tea.

Now that you know this, does drinking tea seem so much more complicated?

Let’s shift gears to tobacco. Please view video on tobacco farms.

Hazardous Child Labor on Indonesian Tobacco Farms, 8:31 minutes

By this point, we all are familiar with the dangers of consuming tobacco in any form. Have you considered, however, the hazardous conditions and risks of the work on tobacco farms? Have you ever considered that children, even very young children are put to work on tobacco farms? Please examine the supply chain infographic for tobacco in Indonesia. As you can see, there are numerous weak links in the chain that allows for rampant labor exploitation to take place.

Source: Business & Human Rights Resource Center. (2019). Indonesia: Hazardous child labour in tobacco farming exposed in Human Rights Watch report. Retrieved from https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/%E2%80%9Cthe-harvest-is-in-my-blood%E2%80%9D-hazardous-child-labor-in-tobacco-farming-in-indonesia

Now, you are probably patting yourself on the back and saying, “I don’t own any slaves—well maybe just a few; I don’t drink tea and I don’t smoke or chew tobacco…so, I am a pretty good consumer.” Right? Wait, you are probably wrong. What about clothing? I am 100% certain that you own clothing—if you are reading this chapter, you are more than likely not living in a very remote island where your clothing is handmade from an animal killed by your bare hands or a bow and arrow. With that being the case, it is a very good chance that you have clothing that was produced in part or whole by someone exploited or enslaved in a supply chain. As seen in the infographic by AGILE ME (2017) below, our favorite “duds” go through a series of stages in the the supply chain that includes processing raw materials, spinning, weaving/knitting, dyeing/finishing, producing/sewing, and getting it to the customer. From the supplier’s perspective, the production/sewing stage has several more layers to it that include fabric supplies, accessory supply, sub-contractors and in-house production.

Sweatshops

How many of us are able to wear an article of clothing and feel 99.9% confident that “this is not a sweat shirt” that was made in a sweatshop or under some form of coercive condition in the supply chain? That is, how many of us are confident that our consumption is not blemished by the reality that a child, forced laborer, or slave had a “hand in it” during some stage of its production in the chain supply? Until you are able to confidently and affirmatively answer that question, the authors would encourage more conscious consumerism.

Sudara’s “Not a Sweatshirt” sweatshirt aims to help victims of sex trafficking by raising awareness and using funds to train and employ former victims in India. Retrieved from https://inhabitat.com/ethically-produced-not-a-sweatshirt-sweatshirt-helps-victims-of-sex-trafficking/not-a-sweatshirt/

Diamonds: A Girl’s Best Friend?

Over the years, diamonds have been marketed as a “girl’s best friend”. The beauty, price tag, carat and clarity are all marketed as the key to a lover’s love and fondness of the receiver. On the darkside, however, the mining of diamonds has long been associated with slavery, murders, and the supplying the funds for terrorist acts by war lords. In response to this reality, the Kimberley process has been implemented as well as the option to be a conscious consumer by purchasing a lab-created diamond. The Gemesis Diamond or Pure Grown Diamonds is one such option for those wanting something different.

Retrieved from https://i.pinimg.com/originals/e2/06/03/e206039106466336ed6af68bea1cd635.jpg

Not all diamonds are “bad” or are “blood diamonds”, but there is enough concern about “conflict” diamonds, that the Kimberley Diamonds Process Certification (KDPC) was put in effect through the Clean Diamond Trade Act on July 29, 2003. The KDPC “is a joint government internationally recognized certification system that imposes extensive requirements on its members to enable them to certify shipments of rough diamonds as ‘conflict-free’ and prevent conflict diamonds from entering legitimate trade” (U.S. Customs and Border Protection, 2019, para 2).

Even with the Kimberley Diamonds Process Certification being in effect, it is still difficult to guarantee that the conflict-free stone that you would like to purchase is actually conflict-free due to loopholes in the system, lack of political will, and diamond sellers producing fake certificates (Armstrong, 2011).

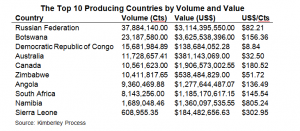

The following countries are top producers of diamonds by volume, value, and price by carats. As indicated here, 7 of the 10 countries are located in Africa.

(Laniado, 2015)

Immokalee Farmworkers

The Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW) is a worker-based human rights organization. It is internationally recognized for these major accomplishments:

- Fighting human trafficking,

- Fighting gender-based violence at work, and

- Pioneering the design and development of the Worker-Driven Social Responsibility paradigm (the Worker-Driven Social Responsibility is a worker-driven, market-enforced approach to the protection of human rights in corporate supply chains).

(Coalition of Immokalee Workers, 2019)

Since 2011, the CIW has come to be known for its Fair Food Program. The Fair Food Program (FFP), an innovative model for Worker-Driven Social Responsibility (WSR), is based on partnership among farmworkers, Florida tomato growers, and participating retail buyers that include:

- Ahold USA (2015),

- Fresh Market (20150,

- Walmart (2014),

- Chipotle Mexican Grill (2012),

- Trader Joe’s (2012),

- Sodexo (2010),

- Aramark (2010),

- Compass Group (2009),

- Bon Appetit Management Company (2009),

- Subway (2008),

- Whole Foods Market (2008),

- Burger King (2008),

- McDonald’s (2007), and

- Yum Brands (2005).

(Coalition of Immokalee Workers, 2019; Fair Food Program, 2019)

Under the Fair Food Program:

- The Coalition of Immokalee Workers conduct worker-to-worker education sessions, which are held on-the-farm and on-the-clock, on the new labor standards set forth in the program’s Fair Food Code of Conduct;

- The Fair Food Standards Council, which is a third-party monitoring system that was created to ensure compliance with the FFP, conducts regular audits and carries out ongoing complaint investigation and resolution; and

- Participating buyers pay a small Fair Food premium. Tomato growers then pass this premium on to workers as a line-item bonus on their regular paychecks. (Between January 2011 and October 2018, over $30 million in Fair Food premiums were paid into the Program.)

(Coalition of Immokalee Workers, 2019)

“DSC_0038” by Mark Auer is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Sri Lankan Migrants

Many researchers attempt to explain human trafficking and persons most vulnerable to being trafficked. The following demonstrate at-risk factors for Sri Lankans. These at-risk factors, sometimes referred to as push and pull factors, place migrants in vulnerable positions that make them susceptible to being trafficked, especially by organized criminal groups and smugglers. Push factors are those variables that make people inherently vulnerable to being preyed on. They may include preventing a person from accessing opportunities or blocking a person from achieving their fullest potential (Hodge, 2008). Pull factors are those misperceptions, false securities, and in-experiences that lead people to believe that the impossible is possible; the realization of “the dream” is accessible to them; and that entering into “shady” or questionable contracts outweigh the perceived possible risks (Logan, Walker, & Hunt, 2009).

PULL FACTORS: Reasons Why Sri Lankans Leave Their Homes for Work Abroad

- Poverty

- Economic hardship

- Economic disparities

- Lack of education

- Low status of women

- Low skill levels

- Government’s encouragement of export labor

- Sexual/physical/emotional abuse in the home (family of origin)

- Abuse by a husband

- Desertion or death of a husband

- Poor supports in the family system

- Drug addiction in the family/individual

- Conflict/wars

PUSH FACTORS: Reasons Why Sri Lankans Choose Arab States and Elsewhere

- Labor market opportunities

- Belief in opportunity to have a good life abroad

- Opportunity to send home remittances

- Perceived freedom from a bad home life

- Opportunity to travel abroad

- Perception that destination country will accept them

- Temporary housing, food and gifts

- Government agreements with other countries to receive Sri Lankans as laborers

- False promises of love and fake marriages

As a destination country, the U.S. is home to hundreds of thousands of foreign nationals who end up trafficked here. Impoverished men and women end up exploited in wealthier countries with little to no recourse for the abuses that they suffer at the hand of traffickers. In the case of Sri Lanka, it is estimated that 10% of the Sri Lankan population are registered migrant workers. This translates into 20% (or 1.8 million persons) of actively employed Sri Lankans (Colombo Telegraph, 2015). Approximately 20% of this population of Sri Lankans, however, find themselves in trafficking situations in the Middle East and elsewhere (Amirthalingam, Jayatilaka, Lakshman & Liyange, 2011). Sri Lankans are sometimes trafficked in Sri Lanka, but most Sri Lankans are labor trafficked in Arab States that include Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Jordan, Oman, Bahrain and Lebanon. Other countries include Afghanistan, Iraq, Maldives, Australia, and Singapore (Amirthalingam, Jayatilaka, Lakshman & Liyange, 2011; “India busts human trafficking racket…”, 2014; Jureidini & Moukarbel, 2004; U.S. Department of State, 2017). Sri Lankan men tend to end up labor trafficked as migrants in construction and other sectors while women report being primarily labor trafficked in private homes as domestics or as migrant workers, too. Some end up sex trafficked as well (Colombo Telegraph, 2015).

Sri Lankans are like most foreign nationals who emigrate from their home countries in pursuit of a better life and labor market opportunities. Push and pull factors are almost identical. Unfortunately, many foreign nationals who end up trafficked come from vulnerable backgrounds in developing countries where opportunities for adequate incomes are far-fetched. Economic depravity, coupled with misconceptions of life abroad, often result in foreign nationals. Poverty, economic hardships, abusive home situations, addiction, lack of support, desperation, and the perception that things are better far away from one’s home, are traits that unlicensed contractors, smugglers, and human traffickers target. According to the Sri Lanka Bureau of Foreign Employment (SLBFE), the official licensing agency that oversees foreign work placements, nearly half a million Sri Lankan women work as domestics in the Middle East. The danger in this widespread, remittance sending (back to Sri Lanka) practice is that it leaves this massive group of already vulnerable women at risk for human rights abuses like human trafficking and even death (Dias, 2016).

To make matters worse, Sri Lankan women are not viewed favorably in the Middle East. Jureidini and Moukarbel (2004) found that Sri Lankan women were paid less than their Filipino female counterparts and were rated as more inferior than their Ethiopian counterparts in Gulf-rich countries because of their 1) low skill level, 2) lack of assertiveness, and 3) lack of education. On average, the live-in domestic Filipina woman was paid $200 to $350 per month as a contract laborer, while the Sri Lankan woman and Ethiopian woman was paid just $100 to $150 per month. The Ethiopian domestic is more positively viewed in the Middle East, however, because they usually have more education than the Sri Lankan woman as a whole. In addition to being paid lower rates and viewed less favorably than her Filipina and Ethiopian peers, respectively, many Sri Lankan contract workers are subjected to complete isolation, little food, long work days, and no social life. This is often the case due to employers abroad changing the terms of the contract upon arrival (Jureidini & Moukarbel, 2004). This “switch and bait” pattern conforms to the criteria for labor trafficking. As previously stated, labor trafficking involves making a person provide labor services for free or far less than what was agreed upon through the use of fraud, force, or coercion (Pub. L. 106-386). As a contract “slave”, there is little to no recourse to being labor trafficked in this way except to work out the three-year term and endure the abuses—for the most part (Dias, 2016; Jureidini & Moukarbel, 2004).

“Sri Lankan New Year” by Indi Samarajiva is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Respecting Human Rights Through Transparency in Supply Chains

Labor trafficking can take place at any stage of the supply chain as evidenced by the previous infographics, video and survey on your consumerism. In an attempt to address this, in part, the state of California enacted the California Transparency in Supply Chains Act that went into effect January 1, 2012. The four-page Act can be found at https://oag.ca.gov/sites/all/files/agweb/pdfs/cybersafety/sb_657_bill_ch556.pdf

The California Transparency in Supply Chains Act requires companies that do business in the State of California to practice transparency throughout its chain through disclosures.

Terms of the California Transparency in Supply Chains Act

- Retail sellers or manufacturers doing business in the state of California with annual worldwide gross receipts in excess of $100,000,000.

- Required Disclosures

- Companies subject to the Transparency in Supply Chains Act must disclose the extent of their efforts in five areas: verification, audits, certification, internal accountability, and training. Specifically, in its supply chains disclosure, a company must disclose to what extent, if any, it:

- Engages in verification of product supply chains to evaluate and address risks of human trafficking and slavery. The disclosure shall specify if the verification was not conducted by a third party.

- Conducts audits of suppliers to evaluate supplier compliance with company standards for trafficking and slavery in supply chains. The disclosure shall specify if the verification was not an independent, unannounced audit.

- Requires direct suppliers to certify that materials incorporated into the product comply with the laws regarding slavery and human trafficking of the country or countries in which they are doing business.

- Maintains internal accountability standards and procedures for employees or contractors failing to meet company standards regarding slavery and trafficking.

- Provides company employees and management, who have direct responsibility for supply chain management, training on human trafficking and slavery, particularly with respect to mitigating risks within the supply chains of products.

(State of California Department of Justice, 2019, Required Disclosures section)

Conscious Consumerism

So, what now? There are federal and state laws in place to keep labor trafficked produced goods out of the hands of U.S. citizens, yet exploiters continue to find ways to break the law and violate the human rights of men, women, and children in the United States and around the world. How do you become a conscious consumer and respect human rights? Please start with the infographic below. After you do that, please read the “List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor” (2018) that can be found in the supplementary readings near the end of this chapter. This annual report is produced in accordance to the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act (TVPRA) of 2005. Next, please download the free app, “Good on You”. It is available for mobile devices as well as other electronic devices (lap top, desk top, iPad, etc.). It, too, is found in the supplementary readings near the end of this chapter. This free and handy app allows you to look up brands and products and it immediately provides you with thorough information so that you are able to make a conscious consumer decision before going with that product. As a consumer, it is important to take action. Now.

In addition to consumers, corporations and the government must all play active roles in being concerned about and addressing the unethical and inhumane production of goods that are consumed by men, women, and children. Human rights violations are rampant in the mass production of goods used by billions of people around the world. Demand an end to child labor and trafficking. UNICEF USA has concrete steps for you to take as indicated in this short pamphlet. Please read it here.

www.unicefusa.org/sites/default/files/UUSA%20Conscious%20Consumerism%20and%20You.pdf

Easy Steps Include:

- Reduce: Consume less. Period!

- Reuse: Restyle what you have. Don’t buy more things.

- Recycle: Buy used and swap with others.

- Research: Read before you purchase.

[Consumers] “can contact companies to inquire about their corporate policies and practices regarding human trafficking. Consumers may also purchase goods identified as slavery-free. There are even numerous online retailers of products made by formerly trafficked persons and purchases would help support their new endeavors. Individuals can also raise awareness by encouraging their friends, family and colleagues to use their consumer purchasing power to address modern slavery.”

(GlobalFreedomCenter.org, n.d., “Consumers” section).

Quiz

Summary of Key Points

- Become a conscious consumer!

- Contact brands or stores and ask them about their supply chains.

Supplemental Learning Materials

U.S. Department of Labor. (2018). List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor. Retrieved from https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/ILAB/ListofGoods.pdf

App: Good On You https://goodonyou.eco/

References

Amirthalingam, K., Jayatilaka, D., Lakshman, R.W.D., & Liyange, N.( 2011). Victims of human trafficking in Sri Lanka: Narratives of women, children and youth. Sri Lanka: International Labor Organisation. Retrieved from https://editorialexpress.com/cgi-bin/conference/download.cgi?db_name=IAFFE2011&paper_id=75

Armstrong, P. (2011, December 5). What are ‘conflict diamonds?’ Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2011/12/05/world/africa/conflict-diamonds-explainer/index.html

Coalition of Immokalee Workers. (2019). Harvard Business Review: The Fair Food Program is among the 15 “most important social-impact success stories of the past century”. Retrieved from http://ciw-online.org/about/

Colombo Telegraph. (2015, June 16). Sri Lanka takes action against traffickers. Retrieved from https://colombotelegraph.com/index.php/sri-lanka-takes-action-against-traffickers/

Dias, K. (2016, October 17). SL women employed as domestic workers in the Middle East: The bigger picture. News 1st. Retrieved from http://newsfirst.lk/english/2016/10/sl-women-employed-domestic-workers-middle-east-bigger-picture/152026

Fair Food Program. (2019). Partners. Retrieved from https://www.fairfoodprogram.org/partners/

Global Freedom Center. (n.d.). Labor Trafficking in Supply Chains. Retrieved from https://humantraffickinghotline.org/sites/default/files/Labor%20Trafficking%20in%20Supply%20Chains%20-%20GFC.pdf

Hodge, D.R. (2008). Sexual trafficking in the United States: A Domestic Problem with Transnational Dimensions. Social Work, 53(2), 143-152.

India Busts Human Trafficking Racket: Sri Lankans Transported for Cash. (2014, August 26). News 1st. Retrieved from http://newsfirst.lk/english/2014/08/major-sri-lankan-human-trafficking-racket-busted-india/50860

Jureidini, R., & Moukarbel, N. (2004). Female Sri Lankan domestic workers in Lebanon: A case of ‘contract slavery”? Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 30(4), 581-607.

Laniado, E.A. (2015). World’s top diamond-producing countries. Retrieved from https://www.ehudlaniado.com/home/index.php/news/entry/world-s-top-diamond-producing-countries

Logan, T.K., Walker, R., & Hunt, G. (2009). Understanding human trafficking in the United States. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 10(1), 3-30.

National Human Trafficking Hotline. (n.d.). The traffickers. Retrieved from https://humantraffickinghotline.org/what-human-trafficking/human-trafficking/traffickers

National Institute of Justice [NIJ]. (2016, September 20). How does labor trafficking occur in U.S. communities and what becomes of the victims? Retrieved from https://www.nij.gov/topics/crime/human-trafficking/Pages/how-does-labor-trafficking-occur.aspx

Polaris. (2019). Labor trafficking. Retrieved from https://polarisproject.org/human-trafficking/labor-trafficking

Pub. L. 106-386. (2000). Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000, H. R. 3244, (2000). 106th Cong., 2nd Sess.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection. (2109, August 6). Kimberley Diamonds Process Certification. Retrieved from https://www.cbp.gov/trade/programs-administration/kimberley-diamonds-process-certification

U.S. Department of State. (2017a). Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons. Trafficking in Persons Report: Country Narrative – Sri Lanka. Washington, DC: Author.