Chapter 5: Collaborative-Interactive Nonfiction Writing: Positioning Students with Significant/Multiple Disabilities As Nonfiction Writers

5.3 A Multimedia Research Project

Last year, my students and I embarked on a lengthy nonfiction writing project in the late winter. I wanted my students to be engaged in a more extensive, formal writing process – writing a research report as required by state standards for fifth graders. The research project was designed to build on my students’ natural curiosity while incorporating digital learning tools and resources that would help me individualize the process to support my students’ learning needs and personal learning styles. All of these things, I hoped, could be accomplished with the multimedia research project I envisioned. My hope was that my students’ final projects would integrate text with some combination of visual images, audio, video, and interesting links to the World Wide Web that supported their research. For me, the beauty of this process was threefold: I would be able to adapt a more traditional writing project to meet the learning needs of my students with significant and multiple disabilities; the digital format would provide many opportunities for collaboration; and my students would have the experience of using technology to present their research to an audience of fifth grade peers and teachers—an increasingly important real-world skill.

I asked my students to think of an animal they wanted to learn about based on what we had read and learned during the school year; they would be required to report on the animal’s life cycle, ecosystem, relationship with plants and other animals, relationship with people, threats to survival, and anything newsworthy. It was important to me that their curiosity would drive their research process. I was open to just about anything within reason. One of my students, Lily, wanted to learn about Emperor penguins. She had recently watched the movie Happy Feet and was fascinated with the life cycle of the Emperor penguin and the unusual caregiving role of the father penguin. She repeatedly looked at images and stories on the Web (e.g. National Wildlife Federation Kids, Who’s the Best Dad?) showing father penguins keeping newly hatched eggs warm on top of their feet. (We later discovered that father Emperor penguins actually cover the egg with feathered skin called a “brood patch.”) I wanted Lily’s palpable curiosity and sense of wonder to drive her research and writing. Considering Karen Wohlwend’s literacy framework based on the idea that children’s “storied worlds” are filled with images based on a stream of messages in popular media (e.g. movies, video games, and toys), I wanted Lily’s writing to build on her passion for these animals and the narrative that was informing her understanding, while creating a bridge to her continued learning and developing literacies.

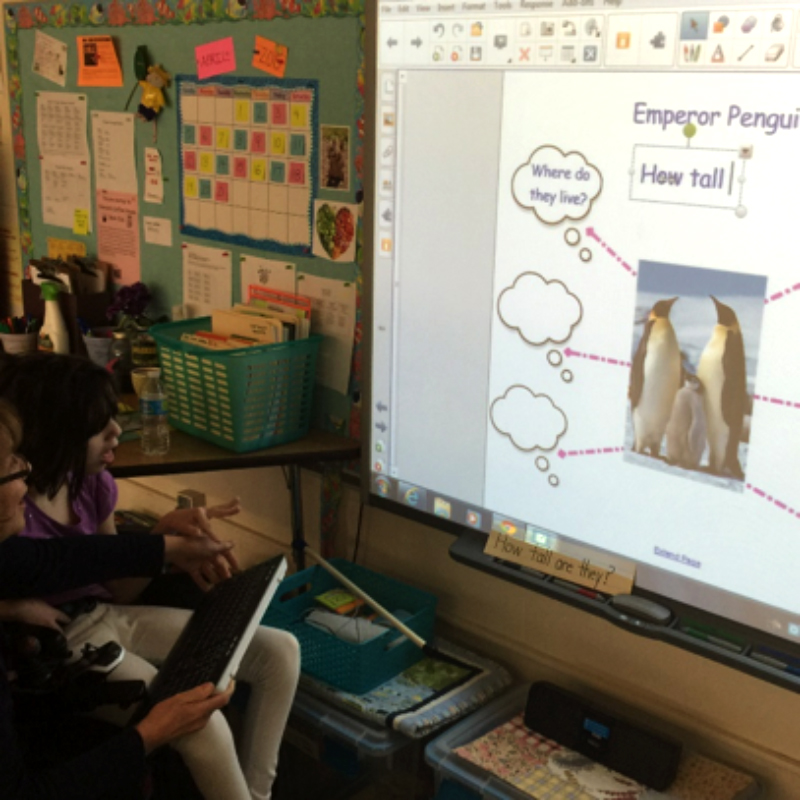

Lily and I began the process by utilizing our digital learning tools to create a simple web. She brainstormed and outlined what she wanted to learn about while I provided technical support and assistance.

Lily used classroom technology – a wireless keyboard with the interactive whiteboard – to complete a graphic organizer as she planned her research. I provided physical support and a model on a sentence strip as she used the wireless keyboard to type the phrase, “How tall are they?”

Similarly Lily used gestures, props, and other paralinguistic cues (e.g. rising and falling intonation) to tell me where the Emperor penguin lives – in the southern hemisphere, on the icy continent of Antarctica. Collaboratively, she and I transformed her expressed multimodal language into a conventional written format along with supporting text features.

Building on the playful nature of Lily’s personality and her individual learning strengths, I used props, puppets, and dramatic play to support her use of language and sense-making through multisensory learning. One day, we made “blubber gloves” using Crisco shortening, plastic gloves, icy cold water and masking tape. Lily and her classmates experienced the insulating properties of blubber (animal fat) in this simulation as they dipped their hands simultaneously in icy cold water—one hand insulated with the blubber glove and the other hand without the insulation. Lily reached the conclusion that the water did not feel as cold on the hand with the blubber glove. We reviewed the notion that insulators (such as blubber) work by reducing the transfer of heat energy; in this case, the Emperor penguin retains its body heat when swimming in the icy Antarctic waters. The blubber glove activity enabled Lily to think about her topic more deeply – specifically how Emperor penguins stay warm when swimming in the icy Antarctic waters.

When she was finished with her research project, Lily used presentation software with the interactive white board and a “low tech” communication device to “read” her report to a live audience of her fifth grade peers (we printed a copy of the report, which served as a replacement for the more traditional written research report). She skillfully combined both images and texts to answer her questions. Then at the conclusion of her presentation, with expertise and finesse, she clicked the mouse on a hyperlink taking her audience to the icy underwater world of these graceful creatures. Lily and her audience listened to an evocative and beautiful instrumental song that complemented the graceful undersea swimming of Emperor penguins. Lily’s nonfiction writing with digital and multimedia tools were deepening and expanding her developing literacies.