Chapter 8: Redefining Nonfiction Writing

8.1 Blurring The Boundaries Between Fiction And Nonfiction: Literary Nonfiction

As students became more motivated and more confident writers, something else happened. The lines between fiction and nonfiction writing began to blur as students made use of aspects from both genres to create interesting, literary writing. While reading Love That Dog by Sharon Creech, we encountered the poem “The Red Wheelbarrow” by William Carlos Williams. When I presented my students with the first line from the poem as a prompt (So much depends upon . . .), I got varying responses. Many students, like Lee, were inspired to write about a personal experience or favorite activity:

So much depends upon a fishing pole on a warm summer day

to help you have fun.

Put bait on your hook

and cast it out.

Then splash! It’s a trout!

You start reeling it in and say,

“That’s a big one!”

Then it’s time you go home for the day with some fine dining.

But others chose to write about something they had observed or had read about in a nonfiction text. Here is what Eva wrote:

So much depends upon a spider

in his web beside the old barn

Watching the flies

buzzing all around

until GULP!

The fly is the spider’s dinner.

As I continued to work with fourth graders, I sought new ways to infuse literary forms often associated with fiction writing into the learning of our content area subjects. Reading, writing, language, and science. Reading, writing, language, and social studies. They all began to blend together in a harmonious mix. During a unit of study on weather, writing stations provided students with opportunities to choose how they would show their conceptual understanding through a variety of reading and writing activities. A narrative story written in the first person as if they were a raindrop or a snowflake allowed them to elucidate what they understood about the water cycle. Using The Important Book by Margaret Wise Brown as a mentor text, students illustrated and wrote about the role clouds played in the water cycle. Fiction writing? Nonfiction? The two got jumbled together in their lively, literary pieces.

Poetry, typically a fictional genre, was also a useful form to help students grasp a new scientific concept, I found. While I introduced them to limericks and cinquains and haiku and diamantes, I also introduced other types of poetry to provide student with ways to communicate their understandings of content area material. Mary, for instance, chose a nested meditation to show her understanding of the water cycle:

Water.

Water

pouring.

Water

pouring

down from the clouds.

Water

pouring

down from the clouds

into the stream.

Water

pouring

down from the clouds

into the stream,

rushing down the waterfall.

Water

pouring

down from the clouds

into the stream,

rushing down the waterfall

into the river to start the cycle over again.

Current events articles also presented students with opportunities to write free form poetry as we sifted through the articles to find main ideas and important details that could be used creatively. During one such lesson we gleaned important details from an article about monkeys in Delhi, India. (Because of overpopulation, the monkeys had become a nuisance for the residents.) After reading and determining the important information, I modeled how we could take that information and use it to write a poem. Later we read another article focusing on New York City leaders’ ban of big sugary drinks due to their detrimental health effects. I then gave students an opportunity to “give it a go” for themselves. Elizabeth wrote this:

Big sugary drinks.

Big sugary drinks.

Big sugary drinks.

People drink too many sugary drinks.

That causes people to become obese.

People are getting heart disease and diabetes.

Stop drinking big sugary drinks.

Too much sugar.

Drink less sugary drinks.

New York’s getting rid of them.

Do we get rid of them?

No, that takes away individual freedom.

Don’t slurp as many sugary drinks.

Don’t make the problem bigger.

As I read Elizabeth’s poem, I was startled by what her writing revealed… Cause/effect. Persuasive writing. Main idea. Humor. It was all there in that short poem. She had sifted through the important information and had gotten to the crux of the article. With this piece of writing I was able to assess what she understood from her reading as well as marvel at the skillful way in which she was able to communicate this understanding to an audience.

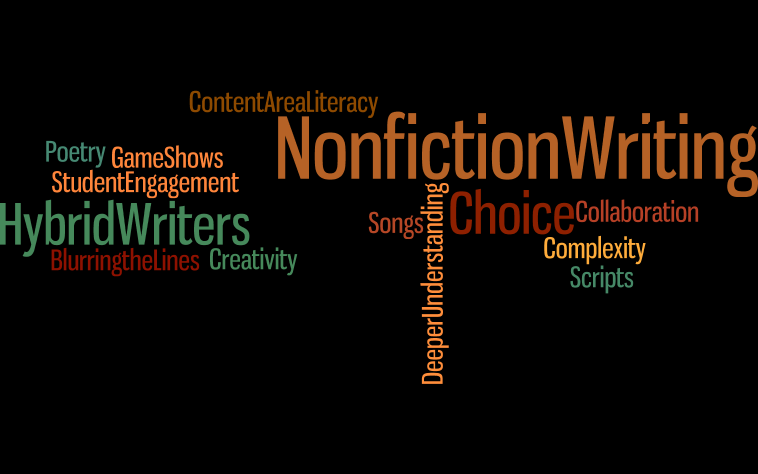

Collaborative learning groups added a further dimension to the ways in which I taught nonfiction writing. As students worked with peers in small groups they had opportunities to learn from each other, experience different perspectives and discover diverse ways of doing things. A lesson on the Native American Indian tribes that settled Ohio was transformed into a Readers’ Theater by one group of students. A lesson on the schools in pioneer times was turned into a play. A lesson on the various modes of transportation in early Ohio became a song which they all sang to a familiar tune. I observed as the kids discussed, disagreed, and finally came to consensus on what content should be included in their scripts and songs. They asked questions to clarify their understanding and made decisions on how best to present their material. They wrote. They erased. They revised and rewrote – together. And then they presented their hard work with smiles on their faces. Some presentations were great and some not so great. But as they grappled with the material through the writing process, they gained a deeper understanding of the content and each other. They practiced speaking in front of an audience and listening to each other. They practiced reading fluency. They read and wrote in new genres and practiced their grammar and shored up their nonfiction text reading skills. And everyone participated and was successful in one way or another.

It seemed clear from my own observations of the students in the classroom that using these forms of writing typical to fiction when writing nonfiction text were benefitting my students in many ways as well as making teaching nonfiction writing, such as formal reports, easier. Students were encouraged to think more complexly, and their understanding of the conceptual material was firmer. Their familiarity with nonfiction text structures improved as they used these features in their writing. Students made choices about how to convey their conceptual understandings of the content they were studying in ways that best suited their learning styles. Relationships were being created through collaborative experiences: students received support from each other when they needed it as they worked together as partners or in groups. Since all students were busy and engaged, I had the opportunity to provide assistance to individuals or groups who needed intervention. Best of all, everyone’s work did not look the same. Further, I had the data I needed to confirm that this intermingling of writing and reading and content was a valid practice; consistently my state scores in reading came back every year with a very high class average in the subcategory of nonfiction text.