Chapter 2: “It’s like we’re learning and having fun!” Writing NonFiction In The Kindergarten Classroom

2.2 Doing the Work of Authors: Transitioning to Formal Instruction on Nonfiction Writing

For the first two-thirds of the year in Kindergarten, our focus in writing lessons was on building confidence and an identity as a writer, basic mechanical lessons (letters, sounds, letter formation, top to bottom, left to right, front to back, using resources, increasing known words, ending punctuation, use of lowercase letters, spacing), adding details in words and pictures, and understanding the difference between writing that lists information or opinions and writing that narrates events in our lives. Around April, students were ready to move into a more formal study of nonfiction and how authors create books that teach and entertain readers. We began by studying the Kindergarten level nonfiction books we had been reading all year. I talked to students explicitly about the characteristics of nonfiction providing instruction on how readers navigate and understand nonfiction by using the table of contents, headings, bolded words, and other nonfiction textual features.

Once students had an understanding of nonfiction as a genre and how it differed from fiction, I extended their thinking by studying with them high interest nonfiction books that were outside of their independent reading levels. My goal was to move their writing to more complex, descriptive text that both entertained the reader and helped deepen their own understanding of topics. In the following sections, I will explain how I used two nonfiction books as mentor texts to provide students with models to write clearer and more descriptive text about a topic. I also describe how students took up the authors’ various text features to write their own nonfiction.

The Octopus’s Garden: The Secret World Under the Sea

I chose the book The Octopus’s Garden: The Secret World Under the Sea by Mark Douglas Norman to start teaching students about the craft of nonfiction. The simply stated, yet fascinating facts make the text comprehensible to young children. The layout is easy to understand, and the information is novel. Each section focuses on a different cephalopod, and tells about its unique features. Attached to the front cover is a DVD with a video of each animal, serving to make the mysterious, underwater world come alive for readers. Learning things most adults have never even considered gave students a sense of sophistication and feeling of importance. High-level vocabulary stretched their comprehension skills. From the hypnotizing color changes of the cuttlefish to the shape changing mimic octopus, we couldn’t stop reading! Our art, gym, and music teachers were left anxiously waiting at their doors as we rushed down the hall late to their classes, and then immediately began bombarding them with, “Did you know……!”

While we read, I talked about how Mark (I always refer to the author by his or her first name with my students) is a scuba diver and has seen these octopuses up close; because of his personal experiences this is a great topic for him. I connected my own love of diving and excitement over seeing my first live octopus. My writing lessons, grounded in this book, were focused on topic selection (i.e., choose something you are an expert about), and using a table of contents and headings to plan and organize your book so that readers can better understand your content. The book’s high-level vocabulary and text layout allowed me talk about some decisions authors make to help draw readers in and learn more. (And because it is a topic I am fascinated by, the children were able to see my undeniable excitement over reading nonfiction.)

This proved to be just the book Ruth needed in order to push her writing forward. She is a smart girl and eager to share her thinking with others through writing. However, the act of writing was difficult for her. It took great effort for her to hear individual sounds in words, match those sounds to letters, and then attend to directionality and formation.

When she announced her topic, nature, to the class, I knew I would need to start conferring with her. Narrowing the topic would help her focus her ideas and lighten the writing task facing her. After chatting, she came to realize her “nature expertise” started with plants, so I helped her frame the book around that more specific topic.

“You could write your book just like Mark wrote his. Each section can be about a different kind of plant you know about, the way each of Mark’s sections is about a different kind of octopus. What plants do you know a lot about?”

And off she went!

My simple nudging to consider the work of one of our mentor text authors was enough to help Ruth get started while also encouraging her to use the text features she had learned about. After listing the different kinds of plants she knew about, Ruth began organizing her book into sections about each plant. On her introductory page she lets the reader know there are different kinds of plants like nectar plants, scary plants and corn. She then goes into detail about nectar plants using a heading (“Plants that have a lot of nectar” ) and adding information with her illustration which shows how sunflower seeds fall to the ground and where nectar is found. Ruth seems to be beginning to understand the purpose of an introduction, by first explaining to her readers that there are different kinds of plants before elaborating on what differentiates one plant from another. Without explicit instruction on how authors select and expand upon topics, and the quick, individualized conference focussing on the concrete example provided by a mentor text, Ruth would have been stuck trying to figure out where to go with a topic that was too big for her.

Alternatively, writing came easily for Samantha. She begged for writing time each day. Whenever students were able to choose what to work on (including during our frequent indoor recesses), you could find Samantha’s eyes glued to her page, crayons and pencils sliding seamlessly across her paper. Moving away from a narrative structure, however, proved to be difficult for her, as she said to me, defeated,

“I don’t know what to write about.”

She often talked about gymnastics, so I suggested this as her topic.

“You like to do gymnastics the way Mark and I like to scuba dive. I don’t know anything about gymnastics, so I am sure you can teach me a lot! Can you try that?”

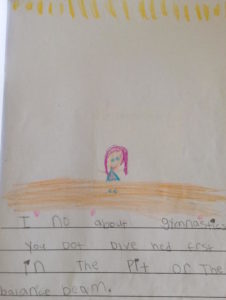

I checked back in with her after writing her first page. She was off to a good start, but needed more support as she continued to write.

“This looks like a good topic for you because you know a lot about gymnastics. On this page, you are telling your readers the rules about gymnastics. That is important information! What other rules do you think your reader needs to know?”

After some discussion, she began writing her next page, so I asked her to check in with me when she was finished and I left her to work independently.

A few days later, her next page read “If you are a big kid, then there is 1 big kid. If you are a little kid, then there is a lot.”

Now that she had a clear understanding of topic and focus, it was time to move the conversation toward refining her writing so that readers could clearly understand what she was trying to communicate.

First, I restated the work she had done. “You have a good start on your book about gymnastics. You tell your readers the rules about gymnastics, and that is really important. I don’t know much about your topic, so you are teaching me important things!”

I began my conference with her by honoring her writing and its message while also naming the work she had done as an author.

Then, I moved to my teaching point.

“You say that ‘if you are a big kid, then there is 1 big kid.’ I don’t know what you mean here. Can you tell me more about it?”

I listened as she clarified, and then we discussed how she could change her writing to make it clearer for her readers. During this discussion I connected her work to our nonfiction texts, as well as books she had written earlier in the year. Adding details to clarify her writing was an ongoing goal, as many of her earlier narrative memoirs had also lacked the details needed to make them interesting. Working on this goal in an informational text helped her to better understand how to write so that readers can understand and visualize information.

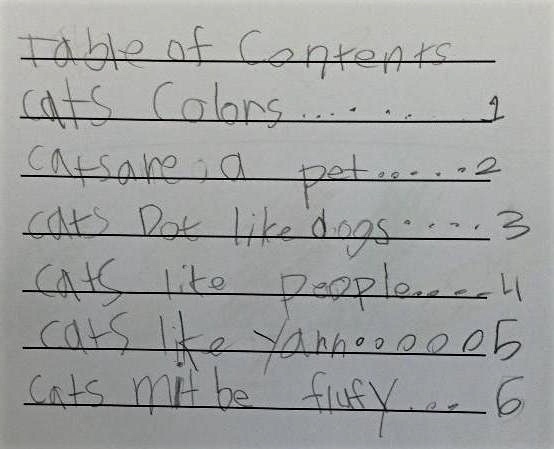

Lyla was yet again a different writer. While she had strong “big picture” literacy skills (comprehension, fluency, understanding of an audience), translating those onto paper required scaffolding. During an assessment on letter sound identification on the first day of school, she laughed at me and said, “I don’t know any of those sounds!” Choosing a topic, cats, was easy, but she didn’t know where to start. I suggested the table of contents, and that would help her know what information to put in each section.

“While Mark has a section for each different kind of octopus, you will have a section for the kind of things you know about cats.”

In case you are concerned that reading the table of contents will spoil the book for you, Lyla has a solution: “I don’t like to write the whole sentence (in the table of contents) because I like it to be kind of a surprise.”

Lyla used her table of contents to organize information for herself and her readers. Further, she didn’t simply repeat the words she has written on each page of her book, but rather made subtle changes to enhance her meaning, synopsizing information (cats’ colors) or suggesting what the reader might learn (cats might be fluffy). Her table of contents in particular was an indication of her realization that someone was going to read this book, and most probably begin by reading the table of contents so that they would know where to turn to find the information they were interested in. And while the information on the specified pages is written using simple sentence structures supported by pictures, here we see the beginnings of nonfiction writing that will grow to become more thoughtful and complex in future years.

Lyla’s Nonfiction (Mostly) Book About Cats

As elementary teachers, we often shy away from nonfiction reading and writing. There are so many great fiction books to use as discussion starters about situations that students encounter in their real lives. Also we are responsible for teaching children how to read and write, a very daunting process when starting with only the most basic print concepts and one that becomes more complicated as we think about the conceptual load of understanding nonfiction content. So, it becomes quite easy to push nonfiction to the side. In doing so, however, we disregard the learning opportunities that come in comparing genres, neglect the needs of students who are more drawn to nonfiction texts, and miss out on the rich content that helps students become more inquisitive and curious about the surrounding world.

Once we had fully digested The Octopus’ Garden and everyone had a good start on writing nonfiction books, I introduced a more complex book, Egg: Nature’s Perfect Package by Steve Jenkins and Robin Page. At first glance, it appears to be a very simple book written in small chunks of text that students can easily comprehend. However, if you have ever read Steve’s and Robin’s work (or even just a page of Egg), you will know the layout is quite deceiving. Their rich description and high-level vocabulary stretch the readers’ thinking and understanding. In order for elementary students to comprehend this content teachers need to provide a high level of support.

I chose to use Egg as our next mentor text because I felt the information was captivating for students. This text also provided text to help me teach reading comprehension and decoding strategies this group needed. Finally it was a good model of some nonfiction features like headings and bolded words. All of these characteristics of the book would, I hoped, spark conversations on craft decisions authors make to help inform and entertain readers.

We spent almost a month reading Egg: reading, discussing, reading again, consulting the illustrations, sharing background knowledge, and reading yet again.

Steve Jenkins and Robin Page write, “A mother splash tetra leaps from the water and attaches her eggs to an overhanging leaf. The father remains nearby and frequently splashes the eggs to keep them moist. As soon as they hatch, the baby fish drop into the water.”

To model how readers comprehend complex text, I consulted the illustration showing us that a “splash tetra” is a fish, and I used synonyms to define “frequently.” I broke the word “overhanging” into its two parts: over, and hanging, and then showed a real-life example of what it means. We acted out how the mother jumps out of the water, and how the father uses his body to wet the eggs. Students shared summer pool memories of jumping out of the water and splashing friends who were “hanging over” the deck.

We began to make personal connections to the text in the book. After reading and discussing, “Animals that lay just a few eggs have a lot invested in each one, so they usually take good care of them. Other creatures employ a different strategy. They produce vast quantities of eggs, then pay little attention to them,” William, a triplet, was able to connect it to his own life as an animal born with multiple siblings versus his little sister who was born as a single baby. “My mom had to be really careful with Gabby (non-triplet sibling)!” Students were beginning construct understanding of the text through our discussions and their own life experiences.

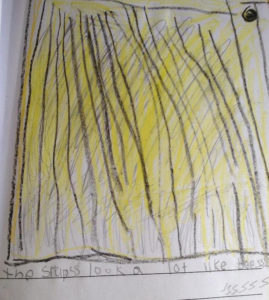

I also saw students make moves in their writing that came directly from our discussions. In Egg, Steve Jenkins and Robin Page use up-close pictures of various eggs so the reader can see the different patterns and begin to imagine the textures. Phoebe applied this strategy in her own book on wasps to help readers understand what wasps look like, comparing a wasp’s stripes to a bee’s stripes.

Phoebe is an avid writer with a folder overflowing with writing, but her books often lack the details needed to help her readers understand the topic more fully. Anchoring her thinking to an exemplary text, Egg, helped Phoebe better consider her readers’ needs and ways she could more effectively describe and illustrate her information. She understood that very few of her readers would have seen a bee or wasp up close, and drawing a more to-scale picture of the two insects would not suffice. My reminder, “You can do that in your book just like (author’s/illustrator’s name) did!” while reading exemplary texts supported Phoebe as she took up this technique independently.

David was another one of my avid writers. He loved sharing factual information and viewed writing time as his chance to record all he has learned about the world. He had spent his entire life studying reptiles and other animals, and typically introduced himself as a reptile breeder. He was truly an expert. Learning how to write factual books came easily to him, but finding ways to make information come alive to reptile novices (like myself) proved to be more challenging.

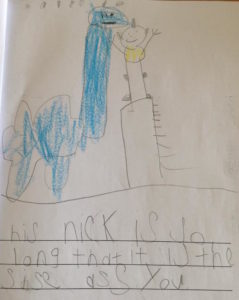

David often wrote about dinosaurs, from fictional pieces about them being teased at school to factual books containing information he had learned over the years. One of the facts he wanted to relay in his nonfiction book was the length of a plesiosaurus’ neck. Based on our readings and discussions, he understood that reader might wonder just how long the neck was, and simply saying “it’s really long” would not adequately describe the length to readers.

In Egg Steve Jenkins and Robin Page explain that the size of an animal’s egg does not always correlate to the size of the animal. To help readers understand the size of a few of these animals, they line them up next to a silhouette of a human, and readers can quickly see how large or small the animals really are. In other books we had read, authors related size to a known object: “It is about the size of a golf ball.” David was able to merge these text and illustration strategies to better describe just how big a plesiosaurus’ neck is. Plesiosaurus’ neck is not just long, but as long as you!

I talked to David about the evolution of his thinking when writing this page. While creating organized and detailed nonfiction books was the goal of the end product, David helped me better understand how studying nonfiction both as readers and writers was much more significant than the books they would write. David was gaining critical thinking skills as he generated an idea, thought through how to best put the information into words so others would understand, actually wrote the text, and then supported his text with a visual representation of the concept he was communicating. The skills he is practicing as a writer now – consideration of an audience, text organization, using comparisons, support with illustrations – will support him in the coming years as he reads increasingly complex and novel nonfiction, and struggles through transforming research into clear, well-written pieces. Additionally, this page took him several days to complete, so he was able to practice the perseverance and hard work required to make quality work.

For David writing about science content was natural. It is the world he lived in comfortably, so refining his craft was my focus with him. Maira was very different. She viewed writing simply as work to complete and took pride in her over-stuffed writing folder. She began Kindergarten with very little literacy understanding, so this was a big accomplishment for her. Knowing few letters and sounds, her pages consisted mostly of strings of letters with a supporting illustration. On one page she wrote, “trbraum.” I asked her to read this to me and, with a confident smile on her face, she spelled out the letters, reading, “T R B R A U M!” As the year progressed, she began copying books she read independently, and then wrote songs and poems she had memorized. I was happy with her emerging ability to use foundational skills to write readable texts, but I wanted to push her to write her own ideas. Studying nonfiction was the springboard she needed: She loved whales and wanted to teach other people what she knew about whales.

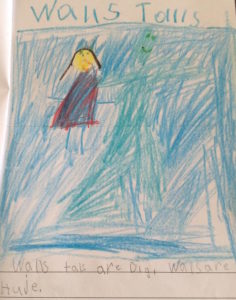

Just as David had, Maira made the move in her writing to show how big whales are by drawing a human next to the whale.

As we examine her text and illustrations we can see that Maira didn’t quite hit the mark as a scientific, nonfiction writer. It is not accurate that whales are just slightly taller than a 5 year old girl as she shows in her illustrations. Further “I love whales” really isn’t appropriate information to include in a factual book. However, Maira shows us what is important and relevant to a Kindergartner. With this work, she shows us how she is taking up nonfiction writing practices to communicate and explain ideas; she is also beginning to write in ways that better inform and entertain readers.

My objective is not for students to write well researched, accurate nonfiction books; rather I want my students to start recognizing that someone is reading and interpreting the information they write. Further I want them to have permission to try out the tools authors use to convey a message in a safe environment. I don’t want them to be afraid of the genre of nonfiction. My eyes are set on a more long-term goal: to support my students in becoming adults who can write persuasive articles with factual information, emails that clearly communicate ideas, and Facebook posts that consider a diverse audience. If we expect them to do this in the years to come, we must begin by modeling and supporting their early attempts, allowing them to try out the work on their own.

Nonfiction reading and writing is often an afterthought especially in the early elementary grades. Complex vocabulary and the background knowledge required for comprehension make nonfiction texts laborious to get through with young children. It can be difficult to find texts that contain enough information to be fascinating yet have enough support for our youngest readers to fully understand. Putting aside our favorite fictional stories to devote the time needed to fully digest a single nonfiction text continues to be a struggle for me. However, this type of work helps students more fully understand other genres by recognizing the features that are required of each. Struggling through information helps prepare them to do the work on their own in later grades. Analyzing how authors move from single facts to fully descriptive pieces helps children see how language can be used and refined to more completely illustrate a point.

Nonfiction writing was defined loosely for my Kindergarten students. Many children missed the mark on scientific fact, as the independent reading and research required to write a complete nonfiction piece was much too difficult for them. However, I provided all of them with opportunities to try out the genre and write about what they knew. Their focus was on conveying information so that others could understand, and so becoming familiar with nonfiction and how to write what they knew to be true.