Chapter 4: Why Bees? Writing Nonfiction Together In Kindergarten

4.5 Complex Content: Writing Nonfiction

It is the second week in May and we have wondered, read, asked more questions, read some more, discussed how writers make decisions, participated in some hands-on activities to solidify content, consulted a beekeeper, experimented on our own with nonfiction writing techniques… and now it was time for my young writers to tackle the challenge of explaining pollination in their own bee reports. But, despite all our preparation, I was worried. Have you ever tried to explain the pollination process to someone and describe why it’s important for food production? I don’t think I ever really thought about it myself until the summer of my parents’ zucchini mystery. The solution to that mystery left me with an understanding of the importance of bees and the pollination process. But how would a five year old be able to understand and explain it? Was the concept so complex that Kindergarteners shouldn’t be expected to explain it?

Further, I was worried that beginning our nonfiction writing with the pollination page might not be the best decision. It’s a complicated concept. Would beginning with writing about such complex conceptual information thwart my students’ stamina for the rest of their work? But I reminded myself that my students had made the unanimous decision to start their nonfiction books by explaining the importance of bees as pollinators. Based on their own original misconceptions about bees generated that first day of the project, they understood that they would have to change the minds of their audience if they were going to save the bees. It was going to be their job to explain why bees are important from the very beginning of their writing. Then they could write about the life cycle and those cool body parts (because those visual images had drawn them in) and end by informing the audience about how to help save the bees.

I continued to feel uncertain. Was it because I didn’t think the students fully understood the process? I reminded myself that I purposely addressed this in Community Writing. I knew it was complex. I wanted us to think through the pollination process and as a community, compose an explanation of pollination. My reasoning was that after several repeated readings, my students would have internalized the language and would be able to access it when they were composing independently in their bee books.

Gathering my courage I decided to begin. I purposely moved Writing Workshop to be the first activity of the morning that day. I wanted our brains to be fresh and ready to work! After referring them to the graphic organizer and pointing out that we would all begin our work on the pollination page, almost everyone chose paper with the fact box labeled, “An Inside Look”. Before we left the rug to begin writing, we discussed that it would make sense to illustrate the inside of a flower in the fact box to show the parts necessary to the pollination process. After pencil caddies and crayon boxes were brought to the tables and my young authors settled into their “studio seats”, I pressed play on the CD player signifying the beginning of our time to write and stood back while they worked.

That night as I reflected on their pieces, I was struck by the beautiful illustrations. Bees were flying from flower to flower. Some students had even used dotted lines to show movement as we had learned from mentor texts throughout the year. Others enlarged the proboscis (tongue) to show it reaching into the flower while pollen baskets loaded with pollen hung off the legs reminiscent of the photographs in our nonfiction books. Still others had chosen to emphasize the stigma and stamen inside the flower both in the fact box and in the illustration itself. Based on this work, I felt my Kindergarteners understood that visual images are integral to communicating knowledge to others especially in nonfiction texts. Moreover, their visual images conveyed accurate and important information about the pollination process.

Next, I took a look at how my scientists explained the pollination process in their writing. The following are some examples:

“A bee collects pollen for us to survive.” Abigail

“Bees are amazing. They give us food.” Emma

“Bees fly from flower to flower.” Etta

“I love bees because they make food for us and everyone in the world.” Daniella

“The stamen needs to get to the stigma. It will die. It will turn into an apple.” Matthew

“If there were no pollination, no food, no us.” Sara

“Bees pollinate flowers to help us survive.” Chase

I confess that I was disappointed. Not that many days before, during Community Writing time, Chase had explained pollination so succinctly and so appropriately for a five year old that we all voted to record his explanation verbatim: “Bees move pollen from one flower to another flower. It has to be the same kind of flower. Then the flower gives us seeds and food.” And yet here he wrote: “Bees pollinate flowers to help us survive.” As a writer, was he satisfied that his illustration of a bee hovering over flowers with arrows to indicate flying and the diagram of the inside of a flower in the fact box gave us the information he wanted us to know? I knew he could explain it more clearly. He said it more clearly while sitting on the rug. Why couldn’t he do it in his writing? And, of course, he was not the only one that I expected more from.

It seemed as though my worst fear had come true. The concept of pollination was too difficult. My students really didn’t understand it deeply enough or hadn’t internalized it in such a way as to be able to communicate it in their written text. Maybe I should leave it alone, let their visuals do the talking. But I couldn’t let it go. So, I did what many Kindergarten teachers do when they want young children to absorb difficult content—we dramatized it!

I had one group of students stand up on one side of the rug representing flowers while another group stood up on the other side representing flowers. The group in the middle were the bees. I gave the first group of flowers some pompoms to hold in their hands. Next, the bees flew over to those flowers, collected some of the pollen, and flew over to the other group of flowers. Then, they reversed the sequence to illustrate that all of the flowers were being cross pollinated. When this was done, the flowers wilted and died, folding their arms around themselves to represent the fruit (full of seeds) that grew as a result of being pollinated.

Later that day, I took a break from math groups and brought groups of students to my table to revisit their pollination pages. I explained that as reader, I wanted to know more about pollination than what they had written on the page. As I worked with each group, I noticed that indeed, they could explain more about the pollination process orally, but in order for them to get more of that explanation on the page, I really had to support the writing process by holding their message for them as they reread and engaged in all of the complex actions I describe as the miracle of Kindergarten writing.

What I learned that day is that I needed to be especially cognizant of the complexity of the encoding process when asking students to write complex content. If I expected my Kindergarten students to write complex ideas and concepts, I needed to be ready to support their oral language as they worked through the lengthy and time consuming task of getting their messages down on paper. With just a little extra support and time, most students could and chose to expand on what they had already written in an effort to make their meaning more clear. In essence, this was more about the process of receiving feedback and trying with support to do what adult authors who participate in a writer’s group do on a regular basis. I had previously introduced the idea of revisiting our work, and we have been giving feedback on a daily basis as authors shared their work at the end of each Writing Workshop session; but this was the first time I specifically asked my authors to try to explain a complex concept in more detail in their writing.

The writing below shows the additions, if any, after the dramatization and small group support.

Writing About Pollination – Before and After

Are these perfect explanations of the process of pollination? No. Did I expect them to be? No. I do think their additions made the pollination process clearer especially keeping in mind that as Kindergarteners, they will be adding an oral explanation as they “read” their illustrations. Most importantly, they learned that they can, with support, work to revise and clarify their writing. And I learned that Kindergarten students can improve their writing with just a little push.

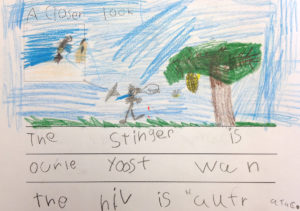

Finally, what did I do about misinformation? What happens when Kindergarteners report facts that are not completely true? For example, this is the page that appeared in Theo’s final book:

This isn’t entirely true since stingers are actually ovipositors and are only found in female insects! So, actually, the stinger is also used by the queen to deposit eggs. (Every year, this realization upsets my Kindergarten boys who are sure that the drones (male bees) are the defenders of the hive!) For Theo’s purpose, he is trying to convey that bees don’t want to sting but they will, especially when the hive is in danger. Again, these young writers are doing amazing, complex work with extremely complex content. At this level, the confusions my students have are developmentally appropriate and, to my way of thinking, completely acceptable. The fact that they are thinking, questioning, researching and composing about content that is exciting and interesting is, in my opinion, much more important than some inaccuracy. I would even go so far as to say that confusion is good. Aren’t adult scientists constantly revising their hypotheses as new information is discovered? As an inquirer of my own classroom practice, I certainly am!