Chapter 2: “It’s like we’re learning and having fun!” Writing NonFiction In The Kindergarten Classroom

2.1 Doing The Work Of Authors: Setting Students Up To Be Writers Of Nonfiction

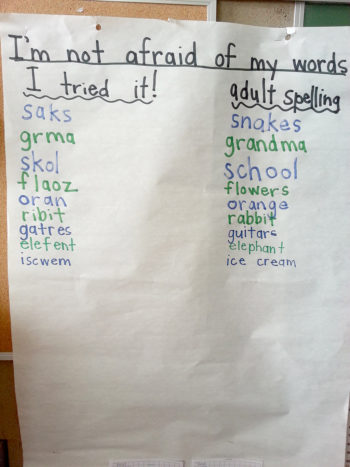

From the very first day of Kindergarten my overarching goal is to have my students write. The main inhibitor to writing is their perception that they do not know how to spell the words they want to write. I have to address this if I expect my students to write texts that are worth reading. So, we begin the year with what they know, using a simple structure: “I like….” My only requirement is that they correctly write “I like,” try the words they don’t know (“Don’t be afraid of it! Just write the sounds you hear.”), and match their pictures to the words. I give them a blank book with two lines on each page, and send them off. “Now go do the work of authors!”

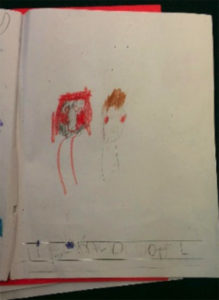

When we give young children the space and time to write, however, we have to be aware of the gap between their oral stories and writing possibilities. For this reason, independent writing time has to be differentiated. One student who illustrates this is Sophie. Sophie is a very strong-willed, eager student with unbelievable self-confidence. In her eyes, there wasn’t anything she couldn’t do. It was not uncommon to hear Sophie, as she walked to her seat to write, say something like, “I can do this! This is easy for me!” When it came time to put pencil to paper, however, all her confidence melted away. She didn’t have the fine-motor control to make her page look the way she envisioned it. Her time was spent writing, erasing, writing, erasing with fury, scribbling, and finally throwing her pencil down in disgust. She didn’t know the letters that matched the sounds she heard, and what came from her pencil was not the perfection she saw in her favorite authors. She regarded her pages as evidence of failure.

I did not regard them in that way, however, and continued to give Sophie the space and time to write. I allowed her to make mistakes and write like a Kindergartner; and I supported her specific needs in individual conferences. We analyzed how her pages looked when there was too much erasing, and agreed to only erase major mistakes. She tried out various types of pencils, and finally settled on a purple wishbone shaped one. We celebrated completed books and didn’t worry about imperfections. I knew that if I expected Sophie to improve her craft as a writer, I would need to allay her sense of frustration.

By the fourth quarter, Sophie’s inner confidence matched her output. She spent day after day practicing rote spelling and handwriting by writing books about things she cared deeply about. She knew unique things about wolves that others didn’t, and she saw this as an opportunity to advocate for her favorite animal. She could match Steve Jenkins’ pattern in What do you do with a Tail like This? and added her own features of nonfiction, just like the authors we had read. Daily practice allowed her to overcome her challenges, and she was now able to entertain and teach her audience using more complex and sophisticated written language.

Over time writing became part of our class culture as we celebrated completed books, questioned for more information, and discussed mistakes. All my students (Sophie included) were excited to share what they had written and to hear what their classmates had created. Writing books was no longer an activity they saw as outside their ability.