Chapter 6: Conversations With First Graders: Scientific Imagination and NonFiction Writing

6.3 Hector And The Mosquitoes

“I ate Hector because I was eating some leaves off a tree and he was sitting on them. I don’t really eat mosquitoes, but he was on the leaf when I chomped down on it and I ate him.” Mark was quite gleeful as he announced this one day.

Then Colin chimed in. “Yeah, me too. I accidentally ate Ned and Kane because I eat plants and they live on branches.” He then opened his mouth wide and made a crunching sound as the others giggled.

These boys were not practicing cannibalism or even indulging in some exotic form of bullying. They had imagined themselves into the persona of the animal they were researching for their end of year reports. Mark, the deer, and Colin, the beaver, had feasted on Hector, the mosquito and Ned and Kane, the walking sticks, as they foraged for food by the pond.

The students in Janey’s classroom were first graders and as playful as would be expected of that age group. Playing around with each other and with what they were learning about were characteristic ways of acting and being for them. This playfulness took many forms in Mrs. Janey’s classroom including joking, making up games and telling stories based on the information that they were learning. The “food chain game” was one such way that students used disciplinary knowledge in imaginative and playful ways as they took on or assigned to someone the role of the insect or animal they were researching.

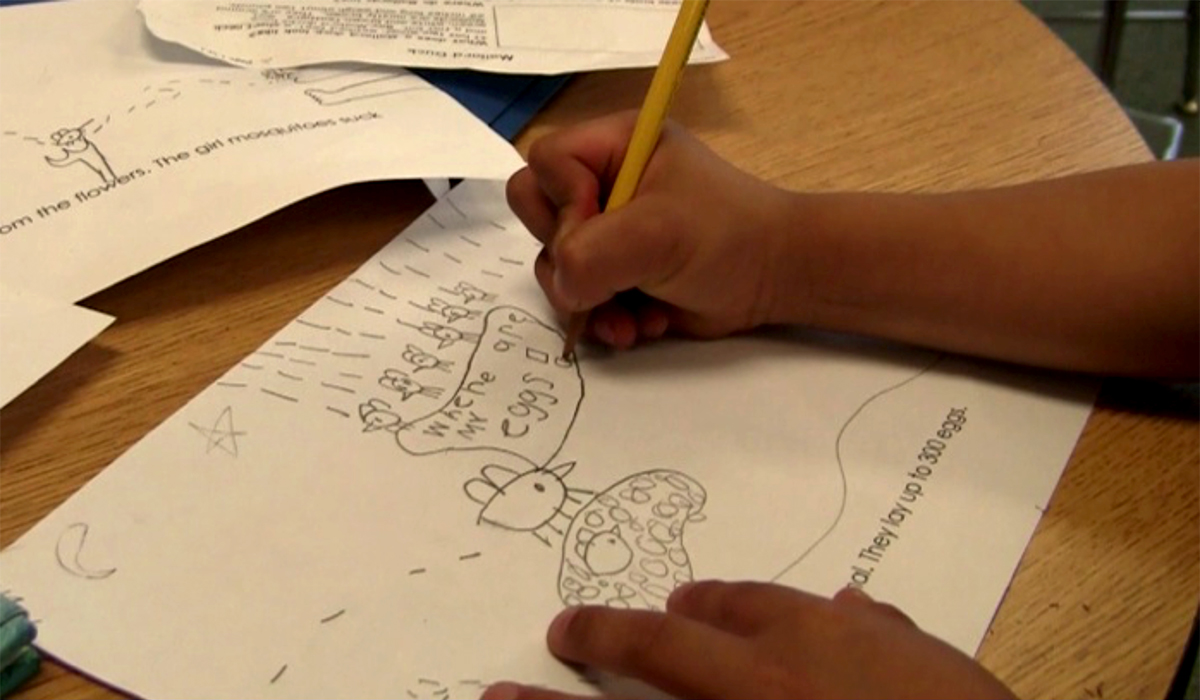

In the end this group of boys came to the collective decision that it was a “bad thing to be a mosquito” because pretty much everyone ate you, even the walking sticks. Yet, despite the bad rap that mosquitoes got in the food chain game, Hector continued to work with this topic of research. At the request of Mrs. Janey, I often sat with him as he worked, and one particular day in May I came over as he was drawing the final illustration for his research report. His last page read: “Mosquitoes…are not mammals. They lay up to 300 eggs.” By the time I came to sit with him he had already drawn a female mosquito on a lily pad resting on a wavy line meant to represent the water of the pond. The mosquito was surrounded by ovals representing the eggs. At this point, Hector had created an illustration that supported and helped clarify the information that was written on the page as was expected of a nonfiction writer. However, Hector decided to go further.

“It’s in the night,” Hector announced as he began drawing a moon and a star at the top of the page.

As he finished drawing the star, I said, teasingly, “Oh, all right. Better watch out for bats then, if it’s night.”

Hector stopped drawing and looked up at me, considering. “No, I want it to be in the day. I don’t want the bats to eat my eggs.” He erased the moon and the star he had just drawn and made a sun instead.

He then began drawing a series of lines coming down from the top of the page which ended in little mosquitoes. As he finished with these mosquitoes he once again returned to the top of the page drawing a V shape in the corner.

“Yeah, but this one is not a mosquito,” Hector said.

I asked, “What’s that one?”

He answered, “A bird,” grinning up at me and then acting out being scared by shivering.

“A bird! Oh-oh,” I acknowledged his quick joke, smiling back at him.

Next he turned his attention to the center of the page where he drew a very large mosquito above the lily pad.

“He’s the big man,” he explained. “And he’s going to be talking.”

“Oh,” I responded rather at a loss for words at this flagrant piece of fiction being introduced into the illustration. “What is he saying?”

Hector drew a talking bubble coming from the mosquito and answered, “Where are my eggs!”

As we finished writing the words for the talking bubble together, I asked him what was happening in the picture.

“These mosquitoes,” he said indicating the smaller mosquitoes at the top of the page, “they’re the friends of the dad mosquito. He’s calling all his friends to come away from the flowers; to come over and see all the eggs the mom has.”

At this point you might be wondering why Mrs. Janey asked me to sit with Hector. We had clearly strayed quite far from what Hector had been tasked with finishing that day. Despite being aware of the other work that he needed to accomplish, though, I sat and listened to him tell me playful stories about this illustration in his research report—stories about what might be possible and true based on Hector’s experiences of his world.

One narrative we constructed was grounded in content knowledge about mosquito predators. To be fair to Hector, I started him on the path of the narrative, by joking with him about what was possible, even probable, within the “story” he was drawing. I implied in my brief comment to him that if it was night time, then bats would be out; and we both knew that bats eat mosquitoes. Hector, after sorting out the implications of my comment, decided to change the time in his picture. He also extended the notion of bats as predators of mosquitoes to their eggs as well (a reasonable possibility, but not true). So, in order to keep the eggs of the mother mosquito safe, he changed the time.

Hector continued this story later in his drawing by adding a stylized bird to his picture (the V shape that is often shorthand for birds flying in the sky). He purposefully drew my attention to this figure with words and actions so that I could follow along with this further extension of our predator narrative or joke. We are both smiling as this narrative ended in acknowledgement that there really is no time in the day when a mosquito is safe from predators.

Then Hector moved onto another story about the dynamics of the mosquito family. In this narrative the proud father mosquito invites his male friends to join him in admiring all the eggs the “mother” mosquito has laid on the lily pad. Of course, there is not factual basis for any of this narrative. Mosquitoes don’t live in family units and, although the males swarm during mating season, they don’t otherwise come together in the way that Hector describes. I suppose the story Hector was telling has its basis in Hector’s observation of his own family dynamics – pride taken in individual accomplishments, the role of the father and the mother, hospitality towards friends, etc. Using his own lived experience of families and how their members act, Hector’s story told through his drawing and talk describes what might be possible or true about mosquito families. What was actually the case, however, was the written text telling about mosquito reproduction.