Chapter 6: Conversations With First Graders: Scientific Imagination and NonFiction Writing

6.2 Marcy And The Dragonfly

“What are you working on today, Marcy?” I asked, sitting down in the empty chair at the table where she sat writing.

“I’m putting in some facts about where the dragonfly’s going…and one fact is that dragonflies fly as fast as a person runs. Another fact is gonna be that a dragonfly’s wings are as clear as windows.”

As I bent over to look at the pages she was working on in her note-taking journal, I saw that she had already written: “I am a dragonfly. I can fly as fast as people can run. I can fly backward and forward and left and right” on one sheet of the day’s practice paper. On a second sheet she was in the process of completing her writing about dragonfly wings: “I am a dragonfly. My wings are as clear as a window.”

Throughout the research report writing which occurred in Mrs. Janey’s classroom during April and May of the school year, students experimented with the language and structure of mentor texts they could use to make their own research reports more interesting. In this instance, Marcy was using the mentor text Atlantic (Karas, 2002), a nonfiction book about the world’s oceans. In this book the Atlantic Ocean speaks in the first person about itself (“I am the Atlantic Ocean. I begin where the land runs out…”) and Marcy had clearly borrowed this structure with her use of the phrase “I am.” She had also taken up the metaphorical language of the book (e.g. “The Pacific and Indian, Arctic and Antarctic are my relatives. We are one big family.”) by using similes to make comparisons between the speed and wing appearance of dragonflies with other known, real-world objects.

As I continued to sit by Marcy, she began her illustrations. She began by drawing a dragonfly flying ahead of a person running. Although she was producing rough sketches, Marcy, like all the students in Mrs. Janey’s classroom, understood that sketches as well as other visual text features common in nonfiction were provided by writers as a way to support and enhance the information written on the page for the audience.

“I’m drawing these lines to show that they are both moving pretty fast,” she told me as she drew several dashes behind each figure.

She then turned the paper over and on the back drew a cross shape. At the end of each point which she marked with arrows, she drew dragonflies. “There,” she said, settling back in her seat, “that shows all the different ways they can fly.”

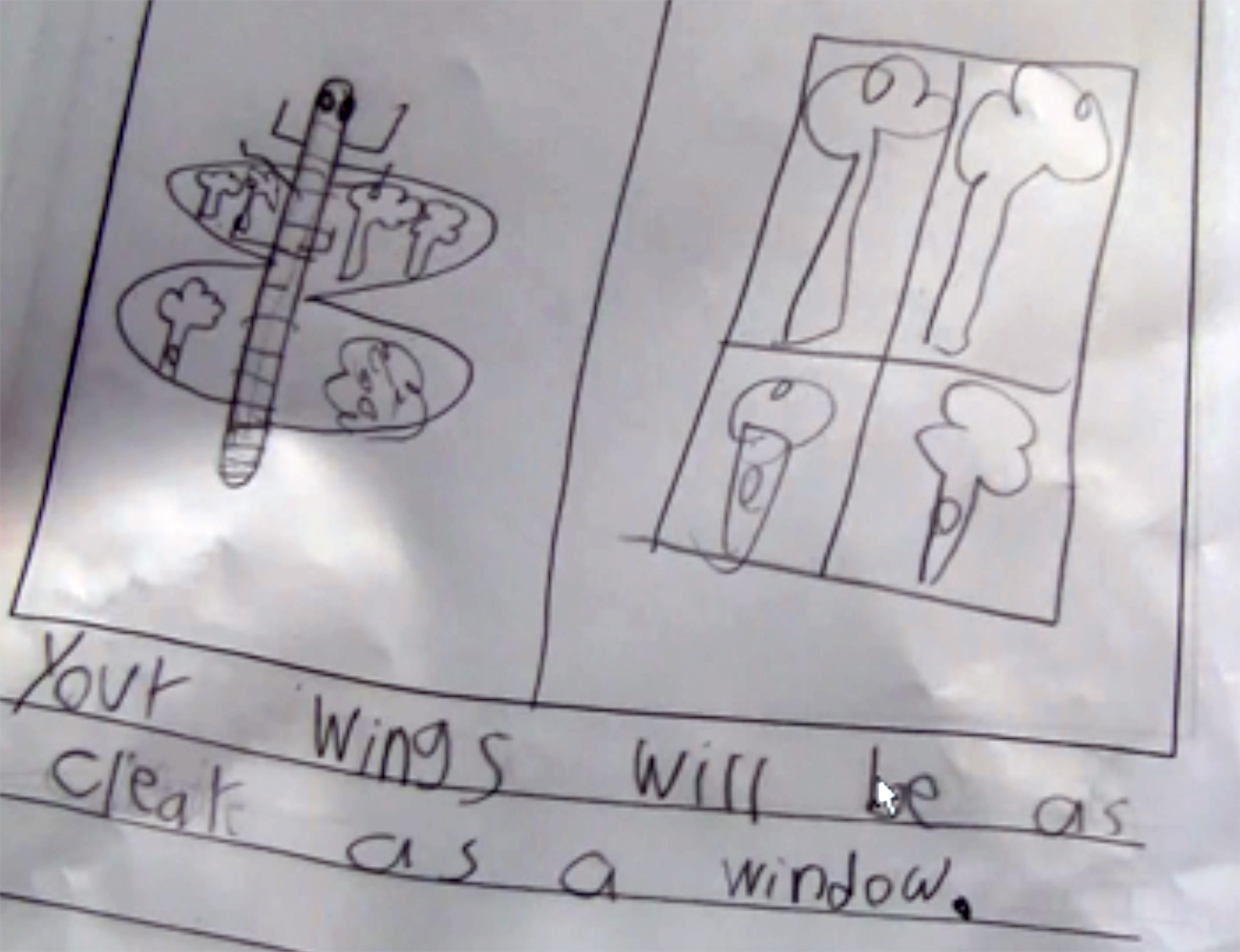

After admiring these drawings with her, I asked if she was going to draw an illustration for her other page of writing. She nodded her head and I told her I would come back and check in with her later. I actually didn’t see her again that day; but the next day, she came up to show me her illustration of the dragonfly wings. Since she had been working with a different mentor text that day, her writing was no longer in the first person. Instead, she had written: “If you are a dragonfly, your wings will be as clear as a window.”

She had drawn a line down the middle of the box for her sketch. On the left side she had drawn a dragonfly body with its wings spread out. On the other side of the line she had drawn rectangles to represent window panes.

Drawing my attention to the trees that were visible within the frame of the dragonfly wing and window panes, she explained: “I made the trees to show you can see through the wings and the window.”

I was suitably impressed, complimenting her on the clear comparison that she had drawn, and she wandered off to continue her writing work for the day.

Marcy, as with many young students, used familiar objects and easily recognizable concepts as she imagined ways to express her understanding of how dragonflies moved and looked. By writing about and showing the dragonfly flying faster than a person running and by explaining the transparency of dragonfly wings by comparing them to window glass, she conveyed what she understood might be possible based on what she understood about the world she lived in and the textual information she had read as she conducted research. These comparisons were represented through metaphorical language structures (as clear as, faster than) and sketches depicting common objects and activities (people running and window panes). For her as a writer of nonfiction, the goal was to represent her ideas so that an interested audience or reader would understand them. For Marcy, then, this drawing and writing created a dialogue where she wrote and drew about what was possible in terms her audience could understand.