Chapter 3: Finding The Balance: Pairing NonFiction and Realistic Fiction

3.1 Take A Peek – A Second Grade Writing Workshop

Their cheeks are flushed and a wave of excitement flows into the room. Recess is over and as my second graders enter, they are breathless and chatty. Footballs are tossed back into cubbies and hoodies are hung precariously on shiny silver hooks. It is time for Writing Workshop and they are itching to go back to the work they left spread out on the tables moments ago.

Sipping my morning cup of tea, I glance at the dry erase board. Seven purple names are scrawled in a list; partners Hazel and Zoe are at the top. They are in need of a conference. I tap my synergy bell and a pitch perfect C-note fills the room. Voices quiet and faces eagerly turn in my direction. “Second Graders, we will work for 40 minutes (I give them the visual on the classroom clock). At 10:45, when the long hand is on the 9, we will meet for sharing. Use your time well.”

These second graders are doing the work of researchers and authors and are busy answering the weather questions they designed. Working in collaboration with a partner, the children are reading, sketching, writing, and whispering (the voice level rule for Writing Workshop) about various weather topics. In this nonfiction Writing Workshop, these young writers are learning to communicate information through writing and visual images (graphs, tables, diagrams, sketches, and word clouds). Students are sitting at tables, on the carpet, and side by side in bean bag chairs – clipboards clutched in their hands. They are surrounded by nonfiction books and print material spilling from bright red pocket folders: diagrams, anchor charts, notes, graphs, weather data, news magazines, and short written responses. All of these materials were generated in the weeks leading up to this day. All of us in room 101, myself included, have immersed ourselves in scientific concepts related to weather. Our learning grows from the experiments, demonstrations, observations, tools, videos, guest speakers and books – fiction and nonfiction – that we have studied. The students are working on the culminating project, a nonfiction weather book. Their audience? The other students in the school, their friends and family. Their real world model? BookFlix – an online resource that matches engaging picture books with high-interest grade-appropriate nonfiction texts.

It is time for conferring and scaffolding, the careful conversations that nudge these learners to a deeper understanding and a connection between the new content, their personal experiences, and past learning. As I move to the conference table, I motion for Hazel and Zoe to follow me. Hazel is up first, as she always is, eager to share her work. From a neatly arranged pile of paper pulled from her folder, she locates her carefully penciled notes. Her research question is written clearly at the top of her page, “How does rain happen?” When I glance at Hazel’s notes, I see bulleted facts—recorded carefully from the nonfiction book she used to find the information she needed, looking much like the modeled note taking I taught over the past several weeks. But missing is a clear connection between rain and the earth’s water cycle— a major concept we explored in books, tested, talked and wrote about.

Hazel’s notes

• tiny droplets of water

• hang in clouds

• bump into each other

• join together

• larger, heavier

• fall as rain

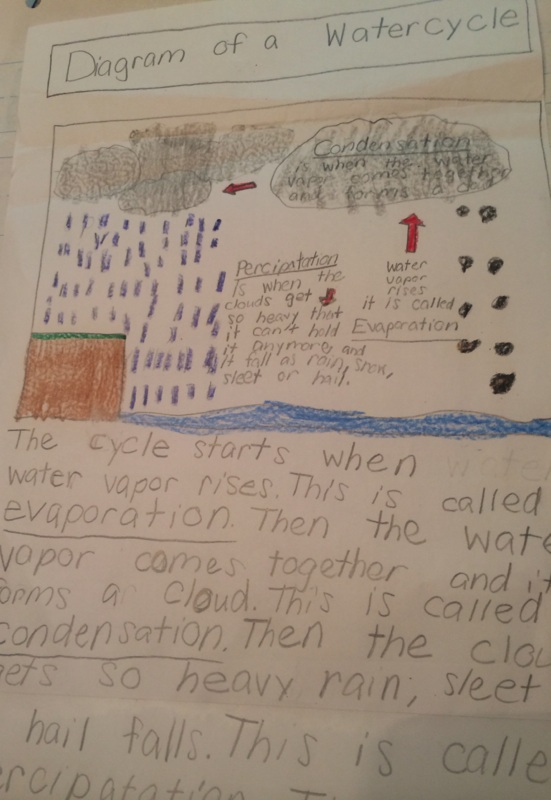

After she shares her notes, I nudge her to think about the scientific process she has outlined in her bulleted phrases. I push her to think about the terminology we learned related to the process. I pull a diagram from her folder – a diagram she created after learning about the water cycle through books, videos, and class experiments (see Illustration 3,1 Diagram of a Watercycle). She smiles and quips, “Oh! The water cycle!” I send her back to add those notes to her graphic organizer. Often times I find that I am called upon to help children make these kinds of connections, connections between the content and the scientific vocabulary and what they have come to understand through hands-on experiences and other sources of information.

Now it is Zoe’s turn. Twelve months younger than Hazel, Zoe is the youngest child in my second grade classroom. In many ways she reminds me of the first graders I taught previously. Always smiling, Zoe needs to work with a more capable other. She is thrilled to be Hazel’s partner. Hazel acts as her model and sometimes coach, boosting her confidence that she can do the work of a second grader. From her jumbled pile of papers, Zoe searches for her research notes and pulls out what looks like a first draft. As she begins to read to me, I realize she has copied the text word-for-word from a nonfiction book. I think to myself, “How did she miss the multiple mini-lessons on note-taking and paraphrasing?” In spite of this, there is reason to celebrate. She has answered her research question, “What comes before a thunderstorm?” with the copied lines of text. This is a sign of growth for Zoe. She located the information she needed. She proudly shows me how she used the table of contents and the index to find what she was looking for. I have learned to celebrate the small steps and not expect perfection. I recognize that now I need to offer her more support on how to paraphrase. Together, we reread the information she located and then close the book. I will ask her to retell me, in her own words, what she read. I might ask her to sketch her understanding or I act as her scribe taking notes (or fact fragments as we have learned to call them) on her graphic organizer. I take a deep breath and turn to her with a smile.

The scenario I describe above is one that occurred well down the road on my journey as a teacher of young elementary students, a teacher who brings both fiction and nonfiction texts together to share with them. In the course of this journey, I met and overcame many obstacles in my path – changing pedagogy, new state and national standards, new school and grade level assignments and my own need to grow as a learner, teacher, and scholar. As I share my journey in the remaining pages of this chapter, I hope that you embrace the meaningful learning experiences possible when teachers intentionally discover the value of pairing fiction and nonfiction texts.