Chapter 7: Nonfiction Is Not Just A Fancy Name For Fiction Reading And Writing Nonfiction In A Second-Grade Classroom

7.3 Teaching Characteristics of the Genre

Since nonfiction books convey information in a variety of ways, Mrs. Kona felt it was important to teach students about the text features associated with the genre. So early on in the unit Mrs. Kona created a lesson where the students did a scavenger hunt with a nonfiction book. Using a form that Mrs. Kona created, students were to read the book and write down information they read from the text features (captions, maps, diagrams, etc.) in that nonfiction book. It did not work. Instead students wrote down the names of text features, ignoring the information, and frequently had questions about how to find the information. As we walked the students to lunch, we talked about the lesson and why we thought it failed. We noted that while students seemed to be able to name the features, they could not tell their purposes or use them to find information.

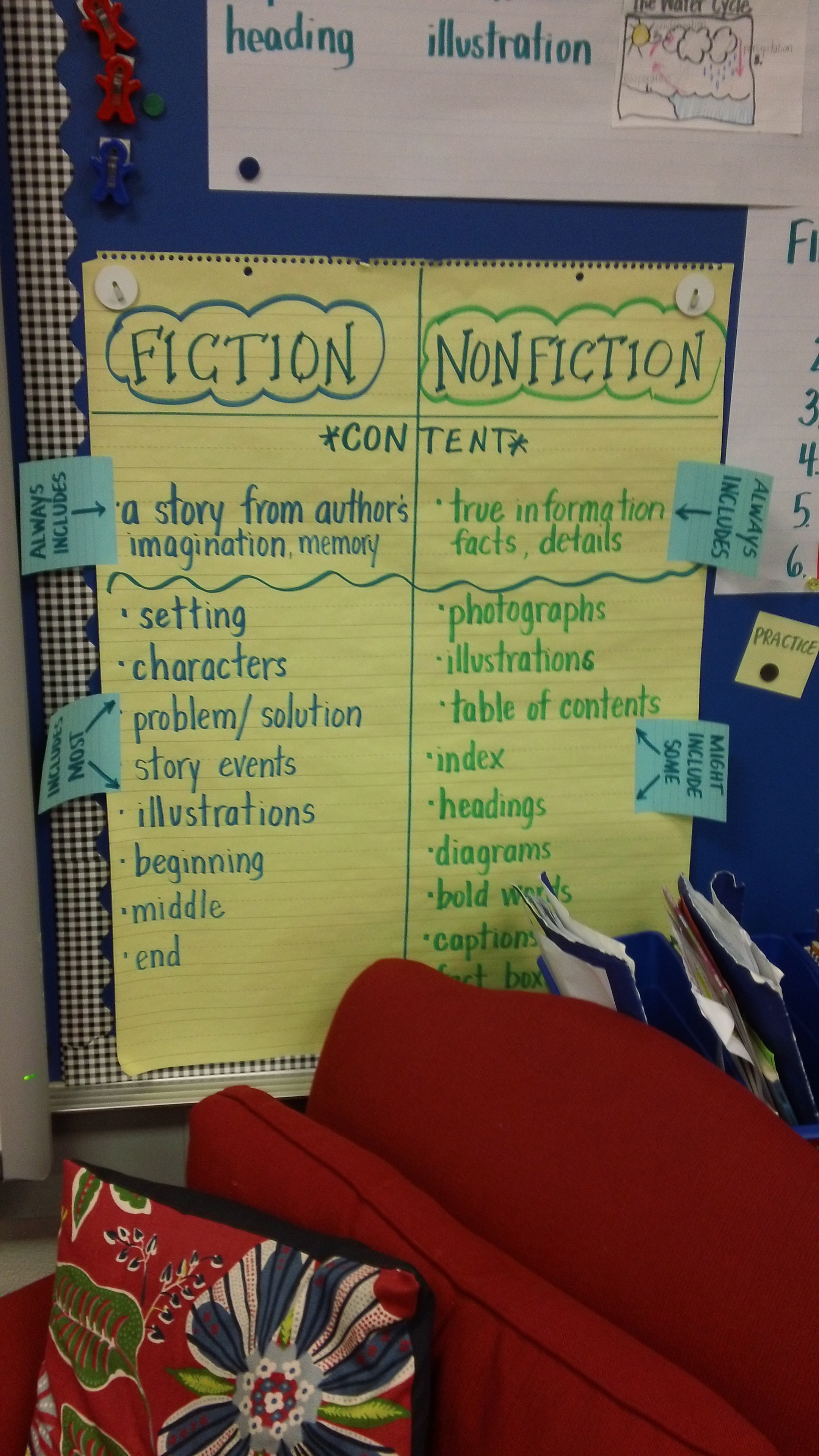

As we investigated further, we discovered that many of the students defined nonfiction as books with a table of contents and a glossary. We were befuddled. What about the content? What about all the other inventive and interesting text features? After realizing this, Mrs. Kona realized that she had to spend some time teaching students about the text features associated with genre. In her teaching she included diagrams, captions, labels, headings, charts, maps, table of contents, glossary, index, bold-faced words, fact boxes, and inserts. Yet, even after introducing and talking about these terms students still seemed to be confused. Sophia told me that bold faced words were just words written in capital letters. When I asked Hazel about a caption, she stated the she had no idea what it was for, and Calvin did not understand how to read a diagram.

Again, Mrs. Kona and I reflected on what to do next. First, we looked at our selection of nonfiction picturebooks, examining how both the design elements and illustrations worked together to attract, interest, and help the reader (or not as was sometimes the case). We began by looking at all of the nonfiction book baskets and the nonfiction books displayed around the classroom. We noticed that some books had too many text features; they all seemed to be competing with each other and we were overwhelmed with what to read and where to focus. Other books had a moderate amount of text features but the book itself was aesthetically bland. There was no color or variation in print or text and, in some books, only one type of text feature was present. As we discussed this issue, Mrs. Kona and I realized that we had similar expectations for nonfiction picturebooks as we did for nonfiction books for ourselves. As Mrs. Kona pointed out, “I’m not going to select a book that has dated photographs or looks like an encyclopedia entry; why would I expect my students to do the same?” Thus, much like Goldilocks on her hunt for the just right porridge, chair, and bed, we looked for books that were appropriate for Mrs. Kona’s young students. We searched for books that had a suitable number of text features portrayed in an attractive yet informative fashion. We looked for books that were exciting to look at but displayed the factual content in a readable manner. We weeded out Mrs. Kona’s book baskets and bookshelves until only the books that we felt met our standards remained.

One such book was The Story of Snow. When we first looked at this “just right” book, we were both struck by the way each page was colored in various shades of dusty blue. There was a mix of microscopic photographs of snow crystals and hand drawn illustrations of snowflakes. Each page spread was different, interestingly so. On one page there was a web diagram that zoomed in and showcased the variety shown in individual snow crystals. Another page had a hand drawn diagram of how snow is formed in the atmosphere. The amount of text varied on each page and alternated between paragraphs, captions, and fact boxes. The content was factually accurate based on the extensive reference list and bibliography. As the reader flipped from page to page, they encountered new and exciting facts about snow on each page. Mrs. Kona and I agreed this was a great book to use for the weather unit. It was, quite simply, fascinating!

Interestingly, it was with a similar book, Snowflake Bentley, where we uncovered students’ misconception about the use of photographs in nonfiction books. One of Mrs. Kona’s students, Grace, originally thought Snowflake Bentley was fiction because of its illustrations. Mrs. Kona subsequently addressed this in several mini-lessons where she asked the students to analyze the content of the text instead of focusing on the illustrations. As a result of this teaching, Grace and her classmates came to understand that Snowflake Bentley was a true story, with accurate information, and where nothing was made up. Based on this experience we intentionally looked for other nonfiction books that used illustrations instead of photographs. By exposing students to nonfiction picturebooks in a wide variety of illustration styles, we hoped to broaden their understanding of the genre.

After working with design elements and illustrations, Mrs. Kona then explicitly taught children about specific visual and textual nonfiction features and how to use them for information gathering. One such lesson focused on diagrams in nonfiction books. Showing a diagram of a volcano, she pointed out the labels, the cut-aways, the use of color, and the arrows pointing to different sections of the volcano. Stressing that the diagram is “trying to communicate information,” the students learned about the formation of the volcano and the flow of lava by looking at the diagram. After this lesson, students put their learning into practice, locating a diagram in a book, writing down what they saw, and explaining what they learned from the diagram. Hazel and Zoe noticed that their diagram of a hurricane was trying to tell them exactly how a hurricane forms. They understood the arrows were pointing out the churning water and the captions were explaining about the eye of the hurricane. These features helped them understand the information.

Of course, Mrs. Kona taught many other lessons focused on nonfiction text features including: the table of contents and how it helped you to find your way around a nonfiction book; other times she would point out the bold words and headings directing the reader’s attention to certain information. There were times when Mrs. Kona, after a mini-lesson, would look over at me and say, “I don’t know if they are understanding this,” worrying about whether students were really grasping these characteristics of the genre. We soon saw that exposure to and conversations about these text features and what information they provided was not lost on her students.

Emmet and Leo became enthralled with the text features that described science experiments or unusual facts or asked readers to play a game. They enjoyed these interesting tidbits of information so much that they created their own science experiment on snow in the nonfiction book they made. Their five-step experiment, complete with illustrations, advised readers on how best to capture and study individual snowflakes. They also loved reading interesting facts about blizzards and were intentional about writing their own “Did you Know?” facts about the Blizzard of 1888 in their books. They were insistent on looking for and providing actual photographs of the blizzard, with Leo stating, “Readers will know it [the blizzard] better if they see the actual photographs.” As a result, Leo’s book included a picture of a person standing next to a towering snow drift with the following caption, “The most terrifying blizzard was in 1888. 58 inches of snow fell. Ohio state struggled.” Because of their understanding of the textual features of nonfiction, Leo and Emmet learned about snow, blizzards, and atmosphere and translated that knowledge into their own nonfiction text features using ideas they had gleaned from all the nonfiction books they had read in class.