Chapter 3: Finding The Balance: Pairing NonFiction and Realistic Fiction

3.7 The Journey Continues – Well Down The Road

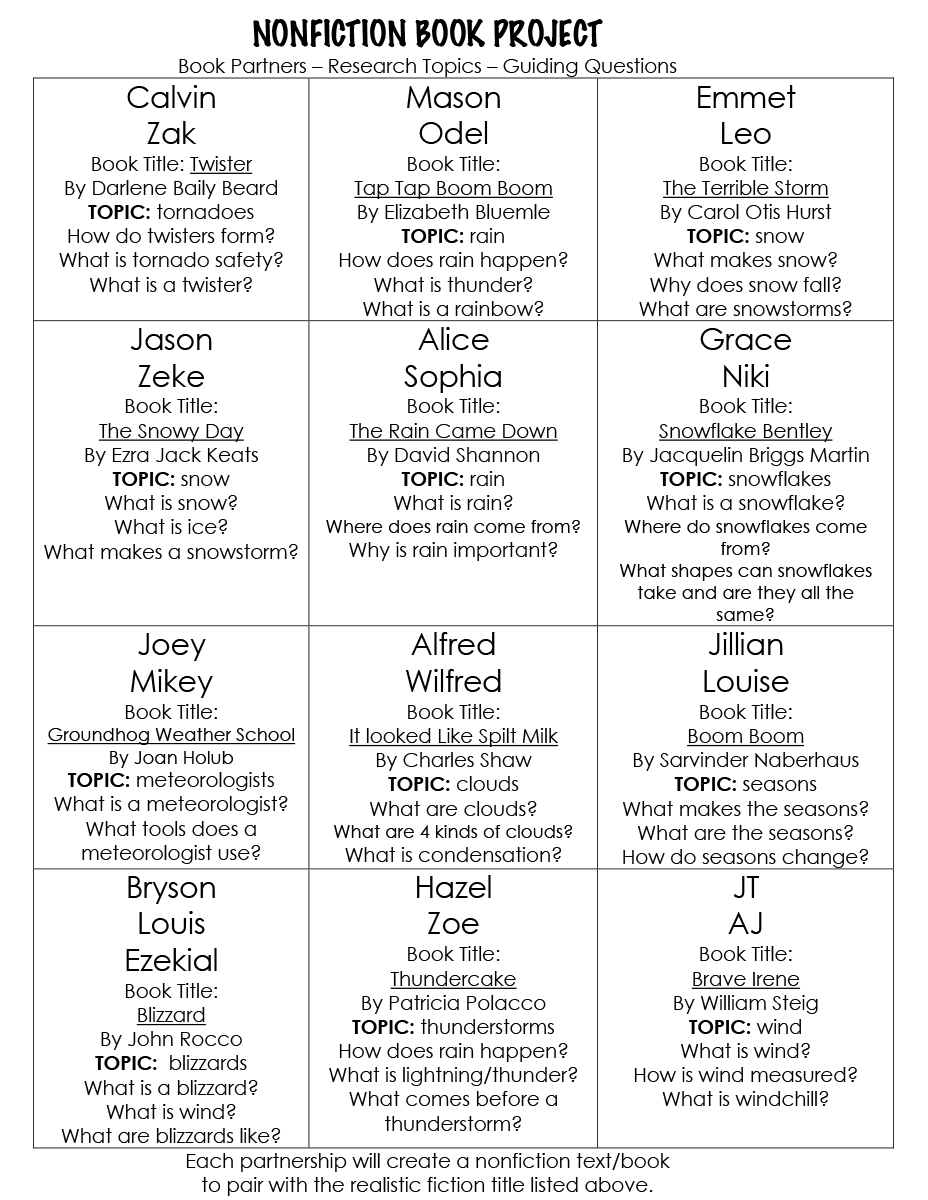

After writing partners selected an appealing realistic fiction text from our shelf of weather books, they decided on the research questions, drawn from the story that would drive their inquiry. Partners Hazel and Zoe chose Patricia Polacco’s Thundercake and recorded the following research questions: How does rain happen? What is lightning/thunder? What comes before a thunderstorm? Their next step was research on these questions followed by the writing and designing of a nonfiction book to pair with Thundercake. Other writing/research partners did the same. As the editor for the project, I gave the following directions for the nonfiction books:

“Your book should include both writing and drawing. It should look like the nonfiction books we read that have print and pictures. You can use your science journals, diagrams, word lists, news magazines, graphic organizers, and any of the weather work we completed in class, the work you collected in your red folder, to help you answer your research questions. This should be a book with your words and research – not something you copied word by word from a published book.”

At this point in the study, I trusted my second graders to do the work I had prepared them for. However, my work as teacher, coach, and editor was far from over. We came upon many potholes in the weeks that followed. I located readable nonfiction texts for children and did book talks to help match books with researchers/readers. This happened frequently and as the study continued students began to do this for one another. It was an amazing and unexpected reality – one second grade researcher assisting another. When Calvin needed information and ideas about tornado safety, Emmet stepped up and suggested a book he’d read during Sustained Silent Reading time on tornado chasers. He described the cover and the title and quickly located the book and placed it in Calvin’s hands. Positioning my students as capable writers, researchers, and authors allowed them to become colleagues and experts for one another.

Through conferences and additional mini-lessons, we tackled plagiarism, inaccuracies, and writing with our audience in mind. The writing pairs designed two-page spreads to share the information they learned in answer to their research questions. They conferred about layout design, headings, illustrations, photography, and ot

her text features. I guided their efforts, suggested changes or additions, and encouraged them to return to the mentor texts that filled the room.

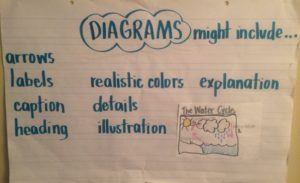

I reminded them of the mini-lessons about diagrams, labels, and captions. I referred them to the anchor charts that hung in the room, the most prominent being our work diagramming the water cycle. After learning about the water cycle and creating our own “water

cycle in a bag”, I taught two mini-lessons on why nonfiction authors use diagrams in their writing. We looked at diagrams in mentor texts, I shared images from the Internet, and we revisited our editions of Scholastic News. We listed the elements we noticed: arrows,

labels, captions, headings, realistic colors, details, illustrations, and explanations. I spent time on sketching and diagramming because they are two ways that young writers often communicate information; further, they serve as tools to help children organize their thinking. I expected many of my students would use diagrams in their nonfiction books because they are both reader- and writer-friendly; indeed, the mini-lessons on sketching and diagramming proved to be an integral part of the nonfiction writing process for my second grade authors.

In fact, diagrams did appear in many of the books the students wrote. Zeke, in his book about snow, created a diagram that included 3 numbered panels illustrating how ice crystals in clouds increase in number and size until they become so heavy they fall to earth. His caption read, “These are ice crystals forming in order.” In his book titled All About Tornadoes, Zak drew and labeled a twisting funnel of dirt and wind and included a caption next to it. Both examples demonstrate how these young writers used images and scientific language to communicate what they discovered in the course of their research.