Chapter 3: Finding The Balance: Pairing NonFiction and Realistic Fiction

3.5 The Next Stage Of The Journey: Pulling Together Mentor Texts, Mini-lessons And Projects

As I started the 2014-2015 school year, I learned of another shift. This year my school district adopted the newly revised state science standards. Gone were the science standards I had used the previous year to plan my Project Based Learning units. Teaching about the earth’s atmosphere was now a major science theme in the standards for second grade. This included concepts related to air, water, and observable weather changes, topics appropriate for seven and eight year olds. The topic of weather was a good choice. Children in Ohio experience firsthand the changing weather patterns, season to season and within seasons. The school yard became our laboratory. We interacted with weather phenomena and on inclement days observed it from the windows of our classroom. Weather affected our lives – how we played, how we dressed, and how we spent our days (Would tonight’s snowstorm bring tomorrow’s snow day?). I was excited about exploring this topic and I knew my students would be, too.

So, once again I collected books. The nonfiction books served as mentor texts and models. I used these books each and every day as part of mini-lessons as I taught my young readers and writers the content related to weather and how to access that information from a nonfiction text and then share it with others through writing. And because of my desire to acquaint my students with both genres, I included realistic fiction texts – stories about windy days, clouds in the sky and foggy mornings. Sharing these stories grounded their growing understanding of moving air and the earth’s water cycle in experiences they understood – chasing items carried away by the wind, getting wet in a sudden rainstorm, or through the experiences of others – children rushing to safety from rising flood waters.

At the start of the unit on weather, I positioned my students in two ways. First, as weather researchers, they designed weather questions, collected data, and conducted experiments. Second, as authors, they examined the text features in the nonfiction books for the way information was shared (diagrams, illustrations, fact boxes, captions, headings and bold-faced words). I regularly asked questions that drew their attention to various text features—“What has the author done to help the reader better understand how wind moves?” Or “Where should I look to find information about clouds? What will help me?” We talked about photographs and illustrations and what we could learn from them. We used the table of contents and the index to navigate the text to locate the information we sought. When we encountered a word in bold-faced print, we turned to the glossary to check the definition.

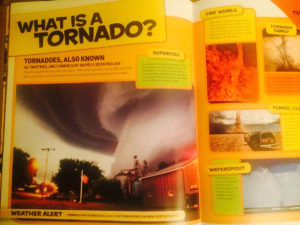

During read alouds I rarely read a nonfiction book cover to cover. Instead, I used the nonfiction texts as supports to build content and background knowledge for the realistic fiction I shared regularly. When I read aloud the book, Twister, a story of a brother and sister who comfort themselves in the cellar as a tornado passes overhead, I paired it with the book, National Geographic Kids Everything Weather: Facts, Photos, and Fun that Will Blow You Away. After inspecting the table of contents in the National Geographic book,

I turned to page 24 and read aloud the information on tornadoes.The information in the nonfiction book in conjunction with the story, Twister, helped students better understand concepts such as tornado conditions, wind speed, and tornado safety. And even more importantly, students talked in empathetic ways about how scary it would be to wait alone in a basement during a dangerous storm. This became the process I used as I paired the fiction and nonfiction books throughout the study.