Chapter 4: Why Bees? Writing Nonfiction Together In Kindergarten

4.4 The Power of Visual Images: Drawing Nonfiction

I have just finished reading the text that goes along with a painting of the blooms of Black-eyed-Susans that have a violet colored rectangle painted over them with an even darker color highlighting the middle of the bloom. The text explains to us that flowers have ultraviolet markings on them that people can’t see but that bees can and that these markings lead bees to the pollen and to the nectar inside the flower. Chase raises his hand and says, “Those pages should be in Incredible Bees. We just learned that and that’s just awesome!” (Event recorded from my classroom, April 2015)

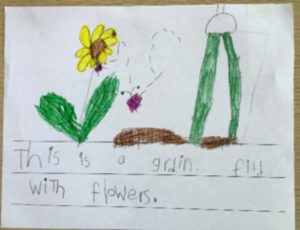

I had to agree with Chase. What a fascinating concept! It’s like bees have super powers! And the technique S.D. Schindler used to paint that violet hued box over the flowers really made an impact on all of us. I marveled aloud over the decisions that authors and illustrators make when they are creating books. We discussed why the illustrator thought it was important to paint that box over the middle of the bloom and decided that this was this illustrator’s interpretation of what the bee sees. I related this technique to a decision that our own Maddie had used as an illustrator in her Writing Workshop story the day before. Her illustration had shown two legs towering over some flowers in a garden. She had explained that she was trying to show how much taller the human was than the flowers in the garden. Wow, adult illustrators make decisions just like us as they pick details to emphasize an important concept!

Schindler’s technique helped clarify a concept in much the same way as the illustrations in the work of Kindergarteners do by complementing the written text with detailed drawings to enhance meaning. However, good nonfiction picture books use a variety of visual images (photographs, diagrams, fact boxes and drawings to name a few) to pull young readers into their pages. Students can look at these visuals and gather information without reading pages filled with lines of text that they are unable to decode or understand. For many Kindergarten students, modeling during read aloud time how to take the information from the visual image and pair it with the meaning from the text is an important way to support them as nonfiction readers.

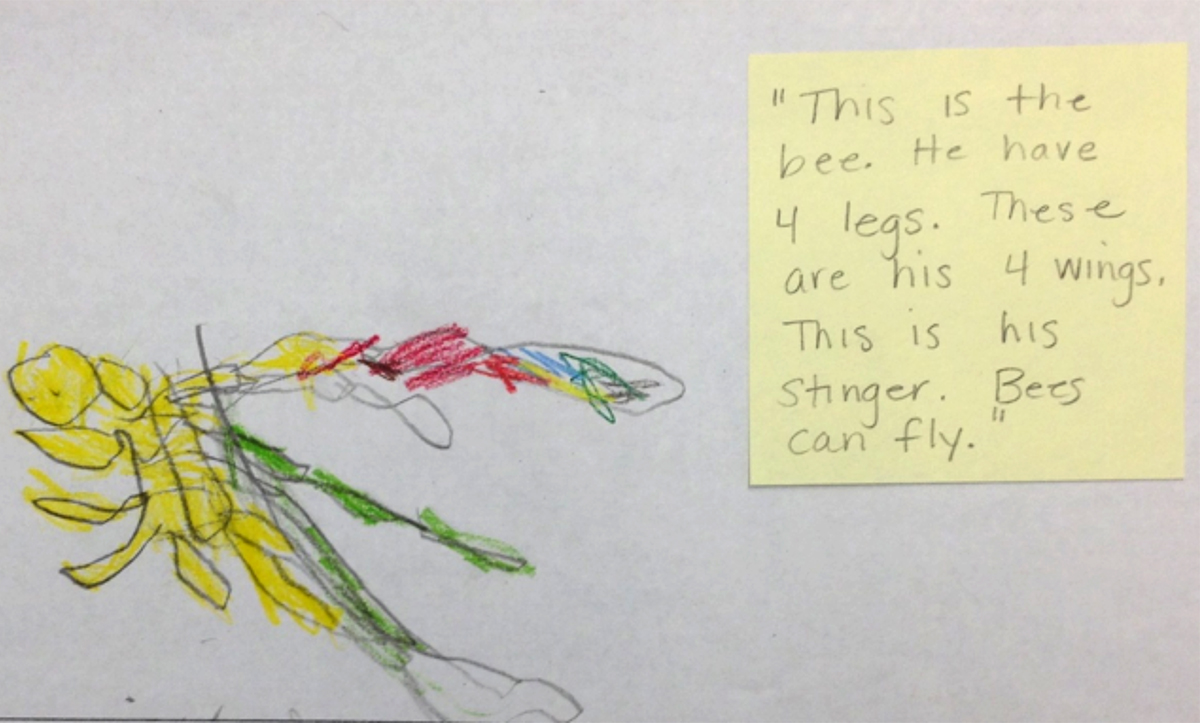

Likewise the visual images that draw us into our nonfiction texts during read aloud time also draw us into our writing work. Just as for some students the visual image was the main source of meaning when reading, for others, the drawing might do all the communicating. Edgar transferred from another school and had not had the rich literacy experiences in his preschool years as the majority of the other students in my class had. His drawing of a bee was one of the most recognizable pieces of work that he produced all year although the written text below his picture was his name written three times. When I asked him to dictate his message, he said: “This is the bee. He have 4 legs. These are his 4 wings. This is his stinger. Bees can fly.” On another day, he dictated to me: “This is the bee again. I put his legs on. That is stripes. That’s a flower. Bees sting kids.” On May 8th, he revised “Bees sting kids” to “Bees help kids.” In his later writing about pollination, he attempted to draw a flower in the fact box and used multiple colors. A less detailed picture of a bee is next to it. He dictated to me: “Bees get nectar. Bees help get people food.” While Edgar’s expressive language was limited, drawing that first bee gave him the confidence and the format to share the content knowledge that he learned (and even revised!) True, some it was inaccurate but even adult scientists are constantly revising their work as new information comes to light.

I even found myself needing to revise based on new information one Writing Workshop as I was working on my drawing of a bee. I explained to my students that I wanted to help my readers visualize the pollen basket. In some of our resources, pollen baskets were described as the large balls of pollen attached to the legs of the bees (as depicted in photographs) that were held in place by long hairs. In another book, we found an illustration that depicted an actual cut, or groove in the leg providing a physical space in which to collect pollen. At this point, we discussed how adult scientists are still learning and questioning, thus explaining why we would sometimes come across conflicting information in our sources. Another caution when inquiring into complex content, but not a reason to stop.

I continued with my drawing and my thinking aloud about how to make decisions as an illustrator. I drew the bee’s leg with the groove in it explaining that this made the most sense to me. As I was drawing, Robert raised his hand. When I called on him, he proceeded to tell me that our beekeeper friend and expert had told Robert’s group during our research trip that the hairs on the legs of bees are like tree branches! What?! None of our resources depicted the hair on a bee in such a way! However, I was not going to discount our expert so I added tiny lines to my hairs so that they looked like tree branches. I thanked Robert for helping me make sure that my illustration in my nonfiction book was as realistic as possible. That’s what writers do! We give each other feedback! At recess time, I ran back to our room to search online. Could this be true? Had Robert understood the bee-keeper correctly? Sure enough, I found a magnified photograph of perfect tree branch hairs on the leg of a bee. My need to be accurate drove me to dig even deeper in my research. This was what complex content was forcing us to do every day. Teaching nonfiction writing this way can be complicated and time consuming. But I believed that this approach helped my Kindergarten students become interested readers and writers of nonfiction.