Chapter 5: Spiritual Anthropologies and Sustainability

5.2 Niebuhr’s Theological Anthropology: Finitude, Anxiety and Sin

Reinhold Niebuhr’s theological anthropology comes from a mainline Protestant (Christian) perspective, and was classically developed in his chapter “Man as Sinner” from The Nature and Destiny of Man, which was developed for his 1939 Gifford Lectures at Edinburgh University. Niebuhr was an American theologian and ethicist, Union Seminary professor, and leading American public intellectual in the 20th century; he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1964 (his brother, H. Richard Niebuhr, was also a famous theologian of the 20th century, at Yale Divinity School).

Niebuhr’s Nature and Destiny of Man is considered one of the top 20 non-fiction books of the 20th century.[1] Historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr considered him the “most influential American theologian of the 20th century,” and TIME magazine named Niebuhr the “greatest Protestant theologian in America since Jonathan Edwards” (1703-1758, the congregationalist/puritan promoter of the Great Awakening). Niebuhr remains influential for his views on American foreign policy and just war theory.[2]

In describing “man as sinner,” Niebuhr elaborated on terminology that is not as common today. Aside from gender exclusive language that many theologians now avoid, Niebuhr’s topic of “sin” isn’t exactly a popular one in contemporary cultural and political discourse, and it might have negative connotations for some readers, so it will help to clarify what is meant by “sin.” For our purposes of understanding Niebuhr, sin can be understood as:

The disruption of human relationship with God by:

-

- Ignoring God’s grace & absolutizing ourselves (pride)

- Ignoring God’s grace & negating ourselves (self-hatred)

- Ignoring God’s grace & over-indulging limited goods (sensuality)

- Rejecting God’s grace & worshipping idols (idolatry)[3]

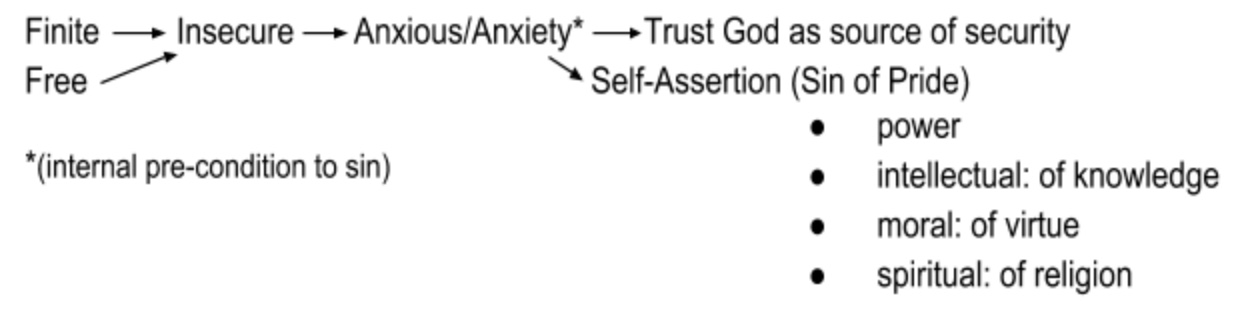

Niebuhr’s basic scheme for describing the human situation of “sin” focuses mostly on the sin of pride (with some reference to sensuality) and can be charted something like this:

Niebuhr describes the human situation as mortal: we are limited, we will die, so we are finite. And yet, at the same time, we are free – we have a sense of freedom, we can step outside of ourselves, think about our finitude, and aspire towards various transcendences of our limited situation, imagining ourselves limitless. However, this juxtaposition of freedom and finitude makes us fundamentally insecure, for no matter how aspirational our vision of what is possible, we will yet die, and we can’t control that, thus making us feel insignificant. This position of insecurity, of being fundamentally limited and mortal, leads to anxiety. Now, Niebuhr notes that being in a state of anxiety is not itself sin, but it is a precondition to sin. (He also notes that for some Christian communities, there will be a strong notion of the devil playing a role in tempting us to believe a false interpretation about reality, which increases our temptation to sin rather than trust that “we’re ok” in some way. To this extent, the situation of temptation is not entirely our fault.)[4]

Niebuhr says the human condition of anxiety is a precondition to sin because anxiety makes us less likely to act well in the face of our insecure situation.[5] Niebuhr suggests there are two main routes for us to then take. We can either trust God as the source of our security, or we can take the path of self-assertion, of trying to assure our own security, often at the expense of or by exploiting others and nature, which gives rise to injustice. This is the path (or sin) of pride, according to Niebuhr. What might be involved in “trusting God” is elaborated more in a subsequent chapter on “Wisdom, Grace, and Power,” and I won’t emphasize that here, but some might liken the notion of trusting God here to “trusting the universe” despite the many dangers implicit in the realities of life. New Testament passages about not being afraid or not needing to worry also come to mind: “consider the lilies…not even Solomon in all his glory was dressed like one of these… how much more will God clothe you?”[6] Hebrew Bible passages describing the Israelites wandering in the wilderness also come to mind – it was in the wilderness, after all, that the Israelites learned how to trust God’s provision and where their well-being was covered despite the harsh conditions of years of desert travel.[7] If God will provide, as suggested by these biblical traditions, the conclusion might be that one needn’t fear for their life or resort to exploiting others and nature out of desperation.[8]

Niebuhr’s prognosis of humans as sinners focuses on the path of self-assertion as the sin of pride; he considers it the besetting sin of the Western world. Niebuhr says there are four main types of the sin of pride:

- Pride of Power – this is the most basic sense of pride, akin to the will to power. For the powerless, it is the drive to gain power over others; for the powerful, it is the act of using power against others unjustly. This is the basic notion of “might is right” – stockpiling resources and protections to be able to fend off all threats. It is thinking that we will be ok, safe, and secure because we’re strong enough to overpower or deter all threats. Niebuhr says our insecurity prompts the drive for power.

Sometimes this lust for power expresses itself in terms of man’s conquest of nature, in which the legitimate freedom and mastery of man in the world of nature is corrupted into a mere exploitation of nature. Man’s sense of dependence upon nature and his reverent gratitude toward the miracle of nature’s perennial abundance is destroyed by his arrogant sense of independence and his greedy effort to overcome the insecurity of nature’s rhythms and seasons by garnering her stores with excessive zeal and beyond natural requirements. Greed is in short the expression of man’s inordinate ambition to hide his insecurity in nature… Greed as a form of the will-to-power has been a particularly flagrant sin in the modern era because modern technology has tempted contemporary man to overestimate the possibility and the value of eliminating his insecurity in nature. Greed has thus become the besetting sin of a bourgeois culture. This culture is constantly tempted to regard physical comfort and security as life’s final good and to hope for its attainment to a degree which is beyond human possibilities. ‘Modern man,’ said a cynical doctor, ‘has forgotten that nature intends to kill man and will succeed in the end.’[9]

- Pride of Knowledge – intellectual pride; this may be the basic sin of the university. It is the sin of modern science (or at least of scientism) when we believe science can know all. It is thinking we’ll be ok because we’re smart enough to take care of ourselves and assure our well-being. Niebuhr says this is a more spiritual sublimation of the pride of power. This form of pride relates to what Niebuhr calls the “ideological taint” that taints all human knowledge. “It pretends to be more than it is. It is finite knowledge, gained from a particular perspective; but it pretends to be final and ultimate knowledge.”[10]

The philosopher who imagines himself capable of stating a final truth merely because he has sufficient perspective upon past history to be able to detect previous philosophical errors is clearly the victim of the ignorance of his ignorance. Standing on a high pinnacle of history he forgets that this pinnacle also has a particular locus and that his perspective will seem as partial to posterity as the pathetic parochialism of previous thinkers[11]…Not the least pathetic is the certainty of a naturalistic age that its philosophy is a final philosophy because it rests upon science, a certainty which betrays ignorance of its own prejudices and failure to recognize the limits of scientific knowledge….Intellectual pride is thus the pride of reason which forgets that it is involved in a temporal process and imagines itself in complete transcendence over history.”[12]

- Pride of Virtue – moral pride; pride of self-righteousness or self-deification. It is thinking we will be ok because we’re virtuous or because we are right while others are wrong, that we’re good while others are bad. Moral pride occurs when:

The self mistakes its standards for God’s standards… Moral pride is the pretension of finite man that his highly conditioned virtue is the final righteousness and that his very relative moral standards are absolute. Moral pride thus makes virtue the very vehicle of sin…. The sin of self-righteousness… is responsible for our most serious cruelties, injustices and defamations against our fellow men. The whole history of racial, national, religious and other social struggles is a commentary on the objective wickedness and social miseries which result from self-righteousness.[13]

And finally, what is really a subset of moral pride, or perhaps the far extreme of moral pride, is:

- Pride of Religion – spiritual pride. Niebuhr says this final form of pride makes the self-deification of moral pride explicit. It amounts to believing not only that we’re right, but that we also have divine sanction; it is believing God is on our side (not on others’) in how we live and understand the world. Niebuhr claims that spiritual pride is the worst and most intractable kind, and it’s been the cause of some of the world’s worst problems: “the worst form of class domination is religious class domination… the worst form of intolerance is religious intolerance, in which the particular interests of the contestants hide behind religious absolutes… the worst form of self-assertion is religious self-assertion… ’What goes by the name of ‘religion’ in the modern world,’ declares a modern missionary,’ is to a great extent unbridled human self-assertion in religious disguise.’”[14]

With this second option, the path of pride (self-assertion in response to our insecurity rather than trusting God) spelled out, we can also consider a third option that Niebuhr comments on in a subsequent chapter: the sin of sensuality. This sin may be more relevant to our discussion of consumerism and materialism in Chapter 12, but it is worth a brief mention here. The sin of sensuality for Niebuhr, in contrast to pride (which attempts to mask our finitude), is the attempt to escape from our freedom. In our insecurity and anxiety that arise from being both finite and free, we can renounce our freedom, often by immersing ourselves in another’s vitality or by turning our devotions to whatever appeals to us. Niebuhr says:

If selfishness is the destruction of life’s harmony by the self’s attempt to centre life around itself, sensuality would seem to be the destruction of harmony within the self, by the self’s undue identification with and devotion to particular impulses and desires within itself.

Niebuhr says Christian theology regards sensuality “as a derivative of the more primal sin of self-love. Sensuality represents a further confusion consequent upon the original confusion of substituting the self for God as the centre of existence.” Having lost the true center of life (God), we are no longer able to maintain our own will as the center of ourselves, articulates Niebuhr. Giving up on finding fulfillment as the unique children of God we are meant to be, we indulge our physical appetites as ends in themselves – we turn inordinately to mutable goods. We will reserve further commentary on the potential implications for consumerism and over-consumption until Chapter 12.

Note that I do not have my students read Niebuhr’s chapter on “Wisdom, Grace and Power,” which is his fleshing out of the implications of the path of “Trust God,” to provide a vision of a Christian alternative to being caught in the sins of pride or sensuality. I won’t focus on that, partly because I find it harder to appropriate than the sin chapter and also because the variety of “solutions” or “salvations” that Christianity, even mainline Christianity, might offer, is too diverse to just focus on Niebuhr’s view.[15]

There are a number of other potential “paths forward” in Christian eco-theology, including the following. Reverend Denis Edwards describes a trinitarian incarnational view[16], which understands that God’s intention in the incarnation (the belief of God becoming human in Christ) was always to be in relation with creatures, so salvation isn’t a plan to fix the mess caused by human sin, but a revealing of the relationality of all life with God. Various liberation theologies[17] emphasize liberation from economic, social, and political oppressions by engagement in aiding the poor and vulnerable through political and civic involvement. Eco-feminist theologies[18] focus on the connections between exploitation of women and of nature, particularly in patriarchal societies. They also aim to reconstruct a (non-hierarchical, non-dualistic) wholistic and just vision of relations in creation; eco-womanism[19] draws on the sacred cosmological perspectives of women of African descent in their struggles for earth justice. Catholic perspectives tend to focus on the sacramentality of nature[20] and have been most recently expressed in terms of integral ecology[21] as described in the encyclical Laudato Si’, which we will study in chapter 8. Some Christian eco-theologies overlap with environmental virtue theory – such as the work of Stanley Hauerwas (which we’ll study in chapter 11) – or Greek Orthodox perspectives[22] (of crucifixion, transfiguration, faith, hope, and love), such as those of Kallistos Ware.

- Niebuhr, R. (1995). The Nature and Destiny of Man: A Christian Interpretation. Westminster John Knox Press. ↵

- For example, see: https://religionnews.com/2016/02/24/reinhold-niebuhr-speaks-2016-american-politics/ ↵

- Migliore, D. L. (1998). Faith Seeking Understanding: An Introduction to Christian Theology (First ed.) Eerdmans. ↵

- In the Biblical creation/garden story (Adam and Eve, and also in the story of Job), the role of the devil is one of tempter. The devil, himself a fallen angel who tried to be as God, now tries to get humanity to follow suit, to try to transgress the bounds set for human life by God. The devil wants us humans to believe that God isn’t caring for us (so we think we must care for ourselves) and to think that God is maybe tricking us, so we shouldn’t trust God’s provision (we’re being made a fool). All such thoughts serve to separate and alienate us from God, which fits the definition of sin as error – missing the mark, being separate from God. ↵

- There are other sources of anxiety as well, such as abuse, stress, and traumatic experience, and these need to be taken seriously in themselves - Niebuhr is not focusing on these sources of anxiety, but rather on the basic existential anxiety of the insecure human situation. Thus Niebuhr's response to existential anxiety will differ from how one would want to respond to other forms of experience-based emotional anxiety. ↵

- Luke 12:27-28. ↵

- The wilderness wanderings story describes where the Israelites became God’s people; you might say they learned to trust God’s provision, or they never would have made it for 40 years. Notably, they didn’t just wait around for God to meet all their needs - even with “manna from heaven” and other seemingly miraculous provisions of food and water, the people were daily engaged in surviving their situation. Beyond this basic level of survival, there was also a fundamental, existential level at which their trusting God shaped them as a community in understanding what it means to be God’s people in the world. Realizing the need to trust God’s provision developed an orientation to the world and a humble sense of one’s perceived power and control in the world which is different from believing we must save ourselves. ↵

- A popular joke suggests some of the common sense line between naive trust in God’s provision and basic survival reality: During a massive flood, there was a man who refused help – as the flood waters encroached the street, a truck drove by to offer him a ride to higher ground, but he replied: “I’ll be ok, God will rescue me!” Later, as the water reached his second floor, a boat came by and offered to carry him to safe shores, but from his second story window, the man replied “I’ll be ok, God will rescue me!” Finally, when the waters had reached the top of his roof, and the man was sitting on the last few shingles that hadn’t been submerged, a helicopter came by to rescue him, but even then, he still refused and said “I’ll be ok, God will rescue me!” The man died from drowning shortly thereafter, and when he got to heaven, he asked: “God, why didn’t you save me from the flood?” and God said: “Well, I sent you a truck, a boat, and a helicopter, what more did you want me to do?” ↵

- Niebuhr, p. 190-191. ↵

- Niebuhr, p. 194. ↵

- Here Niebuhr’s commentary seems to apply to the example in Allen Wood’s article on relativism of a thinker who imagines religions as parochial systems of thought akin to climbers that only have access to one side of a mountain; the author of the analogy seems to imagine himself as above all those views. Niebuhr says on p. 196 that “a significant aspect of intellectual pride is the inability of the agent to recognize the same or similar limitations of perspective in himself which he has detected in others.” ↵

- Niebuhr, p. 195. ↵

- Niebuhr, pp. 199-200. ↵

- Niebuhr, pp. 200-201. ↵

- I also think Niebuhr’s diagnosis of the human situation is more compelling and important to our discussion here than his descriptions of Christian paths forward. In brief, however, Niebuhr’s description of salvation focuses on grace received in faith, the spirit and power of God in humans, the gift of new life, being crucified in Christ (shattering the self in a perennial process of the self being confronted with the claims and presence of God), forgiveness of sins, and the power, holiness, and new life of continually acknowledging God as the source and center of all life. Niebuhr’s theology of the human situation and his framework for salvation and freedom was a primary basis for the healing and recovery process developed by alcoholics anonymous and the 12-step concept in general. ↵

- https://vimeo.com/32557592 ↵

- http://www.landreform.org/boff2.htm ↵

- https://www.encyclopedia.com/religion/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/ecofeminism-and-ecofeminist-theology ↵

- https://www.presbyterianmission.org/eco-journey/2015/06/26/gender-race-environment-and-religious-ethics-eco-w/ ↵

- Denis Edwards and many liberation theologians were/are Catholic. ↵

- https://catholicclimatemovement.global/laudato-si-ch-4-integral-ecology-as-a-new-paradigm-of-justice/ ↵

- http://www.orth-transfiguration.org/safeguarding-the-creation-for-future-generations/ ↵