About the Author

Author’s Frame:

The perspective of this book reflects its author in many ways, so while I have studied and been involved professionally and academically in faith-based environmental work since the late 1980s, and therefore have a reasonably informed view, I also find particular aspects of religious-environmental developments more important or interesting than others because of my own particular interests and background. I’ve never found a text book that quite covers what I teach in religion-environment, and over the years students and colleagues have encouraged me to write my own. So, with support from an Access to Learning (ALX) grant from OSU, I have finally done so.

As may already be clear, I think religion is important in the grand scheme of caring for the Earth, but I will say at the outset that despite teaching at The Ohio State University, I do not subscribe to “silver bullet” hopes that suggest that something like religion, or particular policies, or values, will be The key to solving environmental problems. In fact, I think that looking for any one thing to guide us or solve a large-scale social problem is foolish, and tends to result in shallow understanding. Environmental problems are complex. There will need to be many sorts of solutions and approaches. Religion is one of many things that I think are important in the mix, and that mix also includes science, policy, the arts and humanities, and people in general.

I think religion deserves particular attention because of its social importance, but more importantly, religion has often been either ignored or misunderstood within environmental thinking, and so there is some catching up to do to understand and engage with religion as a more helpful part of the mix. Given how consumptive (and wasteful) American culture tends to be per capita, it may be that religious and spiritual perspectives can help fill in a broader basis for environmental ethics than the secular environmental movement and government policies have been able to achieve so far. To be clear, I don’t think that my approach to religion and the environment is the only or best one. The field of religion and ecology is complex, and involves diverse approaches. There are many excellent programs and statements and books already available, but the particular way I see the elements of religion-ecology dialogue connecting is what I hope to outline in this book, mostly as an aid to my teaching about religion and the environment. If the material I’ve woven together here is helpful to others beyond my students at OSU to understand the complex nexus of religion and the environment, then I am grateful.

Ecological Autobiography:

My students begin their study of religion and environmental values by detailing their own stories as a way to explore and express the values they already hold. I think this is an essential starting point for all of us.[1]

For instance, I grew up with a number of environmental influences, starting with agriculture. My parents were raised on small family farms in northern Iowa, and I grew up on what I often call a 4-acre hobby farm on the outskirts of Columbus, Ohio, where the suburbs gave way to cornfields. [2] When I was young and money was tight, my folks estimate that we raised about 75% of the food we ate, and we relished the low percentage of “store-bought” food in our diet. My mother practiced organic gardening before it was popular, and we regularly processed beans, corn, peas, and berries in long days of canning the fruits of our harvest. Most of our meat came from my maternal grandfather’s farm, stored in our deep freeze in the basement. My brother and I had our own roadside farm stand, where we sold sweet corn, zucchini, tomatoes, and whatever else might be available. Several other families tended garden plots in our backyard, and contributed to our compost pile. We spent many hours working (and weeding!) in our gardens, and in the summer we’d visit my grandparents on the farm in Iowa, where my brother and I would walk the beans, scoop silage to feed cattle, and do whatever other farm chores my grandfather needed help with, for which he’d pay us a going wage.

By the time I was in middle school, my father helped my brother and I start a popcorn business. Using a 1950s Ford 8N tractor and a lot of hand labor, we developed a market for a white, hulless popcorn variety. Within a few years we outstripped the capacity of our 2.5 acre popcorn field, so we began to contract out the planting and harvest of the corn. Though my brother and I dreamed of putting Orville Redenbacher out of business, the shift to hands-off production left us less engaged, and combined with the rise of middle and high school activities, our interest and our business faded. Orville Redenbacher dodged a bullet, and we moved on to other adventures.

The other way my family lived close to the land (and also saved money) was by our choice of vacations. I can remember staying in a hotel only once or twice as a kid, an exotic deviation from our norm. Usually when traveling we either stayed with family or friends, or we camped. Camping trips were our preferred mode for keeping in touch with extended family. I had a great aunt and uncle who moved out to Oregon,[3] and they introduced us to backpacking in the Mount Jefferson Wilderness when I was 6 years old. I was smitten with alpine beauty and mountain grandeur. These and other outdoor pursuits shifted my experiences from an early childhood in the garden to teenage years in the woods and mountains.

In addition to camping and backpacking, I did my fair share of fishing, working hard throughout high school to draw my dad back into a pastime he’d enjoyed as a kid. Like most of his peers, my dad grew up hunting and fishing, but after he finished graduate school, he never found time or interest to hunt, and I eventually lured him into re-developing some fishing traditions. I brought all of these interests with me to college, where I dove into the outdoor education community at Cornell University. My studies in ecology were a nice complement to my growing passion for outdoor education. I took courses at Cornell in Adirondack canoe camping, flatwater and whitewater canoeing, wilderness first aid, and outdoor leadership, and then became an instructor of canoeing, fishing, and outdoor leadership, while also guiding a freshman orientation trip for Cornell’s Wilderness Reflections program. In the summers I worked for the National Wildlife Federation’s Wildlife Camp programs in North Carolina and Colorado, teaching about backpacking, rock climbing, lakes and streams, fishing, first aid, and geology, and co-leading a leadership program for 12-13 year olds. Following college, I took a job with NWF’s new Outdoor Ethics division to help create a program called NatureLink, which we designed to help connect families back to nature by learning to fish. I will expand on some of these points below; suffice it to say that by the time I finished and left college, I was fully immersed in outdoor and environmental pursuits, teaching, and ethics, but there were other important influences I should mention.

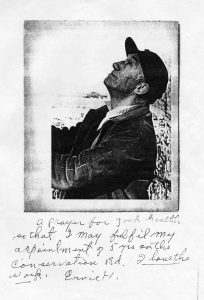

Beyond direct agricultural and outdoor influences, there are also stories and legacies that have shaped me. One example is the conservation ethic of my grandfather Ernie Hitzhusen. He retired off the farm in Iowa in the late 1960s and went into soil conservation. He was an avid birder, and spent many hours birdwatching with my grandmother. He worked for the better part of a decade to help establish the Cerro Gordo County Lime Creek Nature Center, the first nature center in the region. Previously, he’d been the subject of a documentary film called “A Way of Life” by John Deere and Company in 1968 [4], and that film was rediscovered (when it was nearly discarded from an archive box at John Deere Headquarters in Moline, IL) just prior to thanksgiving one year when I was about 9 years old, and became a favorite film to screen when our family gathered. My grandfather’s philosophical quips from the film about life and farming and conservation were memorialized in my mind; for example, the film concludes with his view that: “really we’re just tenants on the land. We have the use of this land, and if we take good care of it, it will live on for the next generation.”

My grandfather was a Methodist layman, and though he likely would not have cited Leviticus when calling humans tenants, his views generally followed from Judeo-Christian values. I also remember my parents telling me to “take only photographs, and leave only footprints” at times when we were hiking or backpacking. And closer to home, we’d regularly hike straight from our doorstep through the many acres of farm and field and forest owned by Ohio State across the road from our acreage on Godown road. Author Wendell Berry talks of the “creek he grew up in”, and without a doubt, mine was the stream in the middle of these fields and forests. As my grandpa Ernie might have said, with so many blessings around us in nature and the wide open, my cup overflowed.

My father was a professor of environmental economics at Ohio State, so I also grew up with lots of dinner-table conversation about sustainable development, and the connection between poverty, hunger, and environmental degradation. I also sat through my dad’s slideshows featuring examples of innovative community and economic solutions to resource scarcity around the world, and heard about his research on the economic and community impacts of acid mine tailings in Ohio coal mining areas. So it may be no surprise that with these sorts of influences, I was relatively environmentally minded. And when awareness of acid rain grew in the 1980s in Ohio, and I realized that the high sulphur coal that was being mined and burned in Ohio (and which supplied the electricity in my house) was responsible for acid rain falling in the Adirondacks, it hit me at a gut level that there was something really wrong with the fact that my flicking on my light switch was contributing to the death of ecosystems in another part of the country. And so I developed a strong interest in ecology as I prepared to apply to college, hoping that by learning about ecology, I might be able to do something to help address ecological degradations around the world, and figuring that the discipline of ecology might also provide more opportunity to spend time outdoors.

I had a rewarding college experience, majoring in biological sciences with an ecology concentration at Cornell University. I was somewhat surprised, though, when my professors taught me that it was the Judeo-Christian heritage that I’d seen in action growing up that was the source of the world’s ecological crisis. My Methodist grandfather was the greatest conservationist I knew, but to hear my environmental science and ecology professors tell it, his value system was supposedly ecologically bankrupt. Some of my courses at Cornell allowed me to pursue this further – the first academic to teach a course in the US on environmental ethics, Dr. Richard Baer (who began teaching a New Testament environmental ethics seminar at Earlham College in 1966 as Chair of the Religion Department) had come to Cornell in the early 1970s and taken up teaching a course titled “Religion, Ethics, and the Environment” (NR407), and this course raised fundamental questions about the nature of religion and environmental ethics. Dr. Baer’s course is the ancestor of the course I teach at Ohio State, and as it turns out, laid the foundation for my career.

There is more to my story. After directing the NatureLink program at NWF, I followed a calling to graduate school, doing joint theology and ecology studies at Yale University at the Divinity School and School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. I worked for the National Religious Partnership for the Environment. I returned to Cornell to complete a PhD focusing on environmental education and ethics in North American faith communities. And I worked for a year as the Land Stewardship Specialist for the National Council of Churches Eco-Justice Programs before moving back to Ohio to become founding Executive Director of Ohio Interfaith Power and Light and to begin my teaching career at Ohio State. Many important and formative experiences occurred during these years, more than I have room to share here (I have added thanks to many of the people who influenced me during those years in the Acknowledgements section of this book). In the future, I hope to create an online archive of ecological autobiographies accessible to anyone willing to submit their own ecological autobiography to the collection. Further details of my own background will be published there, with an invitation for readers to submit their own. In the meantime, I always enjoy sharing more stories in person. Stay tuned.

- This also parallels the story-telling of Michael Pollan in Second Nature, which will be discussed in chapter 3. ↵

- I’ve always said that the line where the suburbs ended and corn fields started was, literally, in my backyard, but that line has long since migrated about 20 miles further from the center of Columbus as the suburbs of Dublin, Worthington and Powell have become more developed. ↵

- My great uncle was a Forest Service volunteer and head of the ski patrol at Mt. Bachelor ↵

- Leading the camera crew was Caleb Deschanel, Emily and Zoey’s dad, during his years as a cinematography student ↵