2. Los Activistas

John Alvarez

JT: Yo nací en Torre, Puerto Rico. Uh, fui a las escuela allá en Puerto Rico y después nosotros nos mudamos a los Estados Unidos, el primer sitio fue Arizona. Y eso fue bien difícil para mí porque fui de isla tropical a desierto. Después, nosotros nos mudamos mucho, aquí en los Estados Unidos. Y, mi papá se retiró en Orlando, Florida.

EF: Entonces, ¿Hace cuánto tiempo que usted vive aquí en Ohio?

JT: Uh, casi ocho años.

EF: ¿Cómo puede describir su niñez en Puerto Rico y en otros lugares?

JT: En Puerto Rico fue difícil porque yo, yo sabía mucho … el problema era que, yo quería más, en la escuela y no me podía ayudar. Y después mi madre me dijo, “Tú sabes, lo mejor es mudarse para los Estados Unidos porque allí vamos a tener la oportunidad de hacer lo tenemos que hacer, y para que los niño crezcan como nosotros queremos.” Así que era difícil en Puerto Rico pero no supe lo más difícil que era vivir aquí en los Estados Unidos. Por algunos años yo quería regresar pero, tú sabes, me acostumbré.

EF: ¿A qué edad vino usted aquí a los Estados Unidos?

JT: Ah, siete años.

John Turner Alvarez Youtube Interview

Mr. Turner’s Interview

EF: ¿Ohio es el primer estado donde usted vive que es frío?¿Cuál fue esa experiencia … en qué temporada llegó primeramente?

EF: Siete años. Un gran cambio me imagino. Pensando en estos años después su niñez, ¿Qué canciones, historias o chistes, siente usted que son parte de usted y su familia?

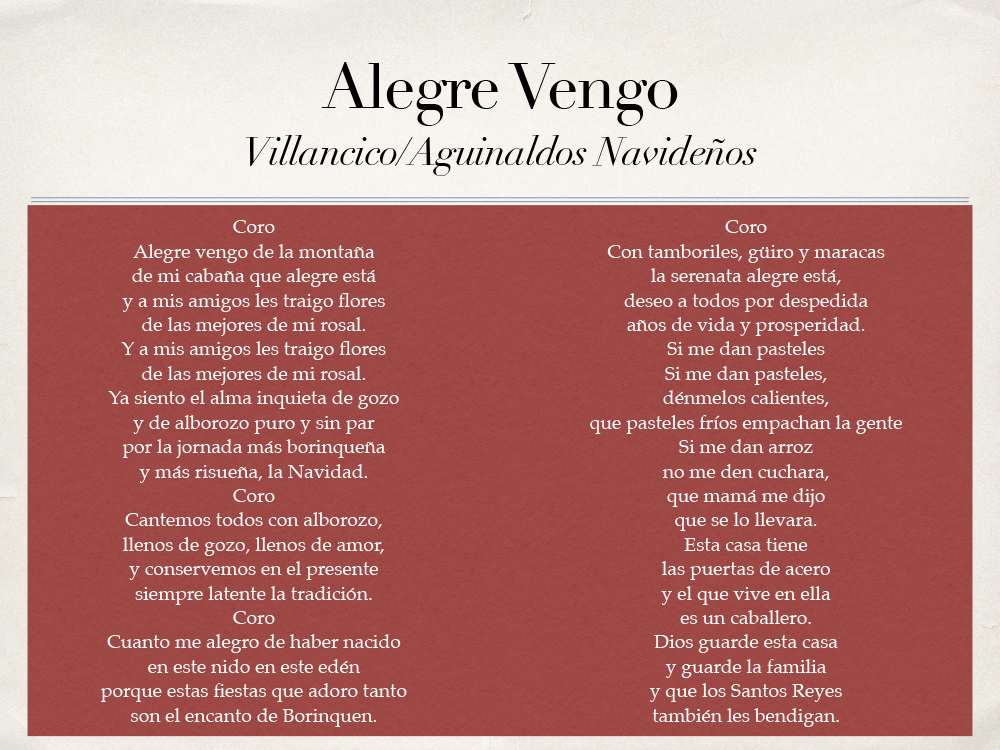

JT: Pues, voy a decir esto en inglés: The part of my life that I miss and that I loved when I was a kid, that is so different here in the United States was Christmas. Christmas in Puerto Rico, there’s no place on the planet that I would rather be than Christmas in Puerto Rico. It is just a more… over a month filled of just partying, people coming together, singing, dancing, great food, and it just seems like everything starts … everything’s commercialized here after Thanksgiving and, in Puerto Rico it’s just not like that. It’s just that coming together and then, the song that always rings in my head and I sing it, and I don’t sing it too much here in Ohio because there’s nobody to sing it with (risa) um, but I always sing uh, “Alegre vengo de la montaña de mi cabaña que alegre está. Y a mis amigos le traigo flores de las mejores de mi rosal.” That’s a typical Christmas song and, and it brings back the smells, the feeling that you get, that just … it’s just unique.

EF: ¿Usted ha tratado de mantener, por lo menos una parte de eso aquí en Estados Unidos o en Ohio?

JT: Pues, aquí en Ohio es muy diferente. En Florida, sí, pude hacer mucho de eso. Pero en Ohio es bien difícil porque, nosotros comemos cosas muy diferentes. Yo odio ese jamón que hacen aquí con miel y, (expresión de asco). Nosotros en Puerto Rico comemos pernil y, ellos no tienen eso aquí. Y así que yo soy homosexual, yo soy gay, y yo tengo una pareja de catorce años y la familia de él son bien alemán, y ellos comen todo eso y yo dije un día, “Oye, vamo a comer comida tradicional de Puerto Rico en estas Navidades” (risa) y, ellos dijeron, “Okay. ¿Qué va hacer?” I go, “Suprise” okay. So I called my mama, and then I called my sister and I said, “I need to know how to have the perfect recipe to do a pernil” sure enough they gave it to me. I did it, I followed it from everything I remember my grandma doing, yo lo hice. I have never seen people devour a pernil and I’m telling you they ate the cuero, cause we leave the cuero and everything, and I went out to a butcher out in the country of Portage County and I was in shock cause they actually gave it to me fresh and I said, “You must’ve killed a pig back there because that’s fresh” (risa) and it just, they just devoured it and they loved it. Lo único que no les gustaron fue los pasteles que eso es diferente de lo que se acostumbran, que esto no es un ‘cake’ this is a, esto, es como un tamal hecho por los tainos. And so uh, they didn’t like that because it is an acquired taste. So, I love it and that’s all that counts—it reminds me of being back in Puerto Rico. Even reminds me of being back in Florida.