Module 3 Chapter 4: Participant Recruitment, Retention, and Sampling

Until this point, most of our discussions have treated intervention and evaluation research as being very similar. One major way in which they differ relates to participants and the pool or population from which they are selected. Recall that intervention research aims to draw conclusions and develop generalizations about a population based on what is learned with a representative sample. Thus, intervention research is strongest when the participants are systematically drawn from the population of interest. The aim of evaluation research is different: the knowledge gained is to be used to inform the practice and/or program being evaluated, not generalized to the broader population. As a result, evaluation research typically engages participants receiving those services. While the principles of systematic and random sampling might apply in both scenarios, the pool or population of potential participants is different, and the generalizability of results derived from the sample of participants differs, as well. The principles learned in our prior course about sampling and participant recruitment to understand social work problems and diverse populations applies to social work intervention and evaluation research for understanding interventions. Because much of evaluation and intervention research is longitudinal in nature, participant retention, as well as participant recruitment, is of major concern.

In this chapter you :

- review features of sample size and filling a study design, and learn how they apply to effect sizes and research for understanding social work interventions;

- review features of participant recruitment and retention, and learn how they apply to research for understanding social work interventions;

- learn about random assignment of participants to study design conditions in intervention and evaluation research.

Sample Size Reviewed & Expanded

Sample size is not a significant issue if interventions are being evaluated from a qualitative approach where the aim is depth of data rather than generalizability from a sample to a population. Sample size in qualitative studies is generally kept relatively small as means of keeping manageable the volume of data needing to be analyzed.

Sample size does matter in quantitative approaches where investigators will generalize from the sample to a population. In our prior course you learned how sample size matters in terms of the sample’s ability to represent the population. Remember the green M&Ms example where the small samples were quite varied compared to each other and to the true population, but the larger (combined) samples were less different? Sample size issues remain important in intervention research where generalizations are to be made to the population based on the sample. This might be an issue, as well, in evaluation research where there are many participants involved in the intervention being evaluated and the investigators choose to work with data from a sample rather than participants representing the entire population served. In either case, intervention or evaluation research, investigators need to determine what constitutes an adequately sized sample. Two issues need to be addressed: numbers needed to fulfill the requirements of a study design and sample size needed to detect meaningful effects.

Filling a quantitative study design:

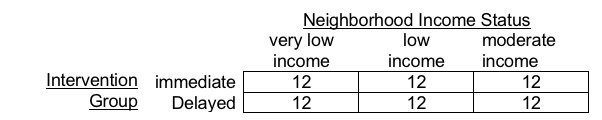

You may recall from our prior course how a study design relates to the number of study participants that need to be recruited (and retained). The study design might include two or more independent variables (the ones being manipulated or compared). To ensure sufficient numbers of participants for analyzing these variables, investigators need to be sure that participants of the designated types are recruited and retained so that their outcome (dependent variable) data can be analyzed. Here is an example of the numbers of each type needed to fulfill a 2 X 3 design. This example has neighborhoods as the unit of analysis; individual participants are embedded within those neighborhood units. This example is relevant to research for understanding social work interventions at a meso or macro level.

Imagine a study concerning the impact of a community empowerment intervention designed to help members of local communities improve health outcomes by reducing exposure to air and water environmental toxins and contaminants inside and outside of their homes. Investigators are concerned that the intervention might differently impact very low-income, low-income, and moderate-income neighborhoods. They have chosen to conduct a random assignment study where ½ of the neighborhoods receive the intervention immediately and the other ½ receive it one year later (delayed intervention with the no intervention period serving as the control). They have determined that for the purposes of their analysis plan, they need a minimum of 12 neighborhoods in each condition. The sampling design would look like this:

Filling the study design cells for this 2 X 3 design requires a minimum of 72 neighborhoods (6 cells times 12 units each=72 units total). These would be recruited as: 24 very low income, 24 low income, and 24 moderate income neighborhoods. Within each neighborhood, they hope to engage 15-20 households, meaning that they will engage with between 1080 and 1440 households (15 x 72=1080, 20 x 72=1440).

Sample size related to effect size.

Previously in this chapter you read about differences that are clinically meaningful. Intervention researchers are often asked to consider an analogous problem: what is the size of the effect detected in relation to the intervention? While an observed difference might be statistically significant, it is important to know whether the size of that difference is meaningful. Effect size information helps interpret statistical findings related to interventions—their power to effect meaningful amounts of change in the desired outcomes. The size or magnitude of the effect detected is determined statistically, and sample size is one part of the formula for computing effect sizes. As a result, the size of a study’s sample has an impact on the size of effect that can be detected.

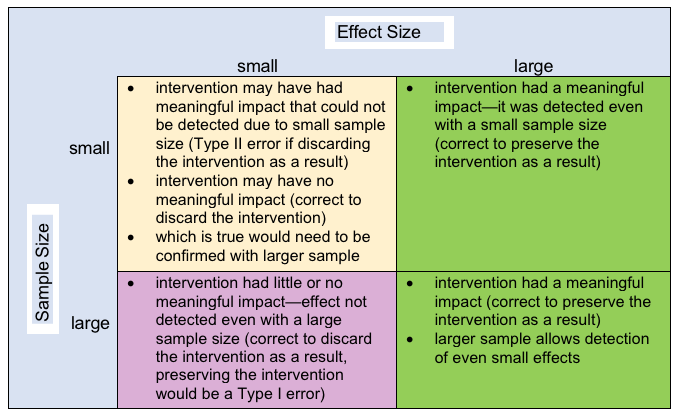

Here, the logic can sometimes become a bit confusing. This diagram helps explain the relationship between effect size and sample size without getting into the detailed statistics involved.

In other words, if an investigator wishes to be as sure as possible to detect an effect if it exists, a larger sample size will help; having a small sample leaves the question unanswered if no effect is detected (see the small/small peach colored box)—the study will have to be repeated to determine if there really is no effect (see the large/large pink colored box) or there actually is an effect of the intervention—large or small.

In order to refresh your skills in working with Excel and gain practice with the topic of sample size related to effect size, we have an exercise in the Excel workbook to visit.

Interactive Excel Workbook Activities

Complete the following Workbook Activity:

Participant diversity.

In our prior course we also examined issues related to participant diversity and heterogeneity in study samples. Intervention and evaluation research working with samples need to consider the extent to which those samples are representative of the diversity and heterogeneity present in the population to which the intervention research will be generalized or the population of those served by the program being evaluated. Ideally, the strategies for random selection that you learned in our prior course (probability selection) aid in the effort to achieve representativeness. Convenience sampling and snow-ball sampling strategies, as you may recall, tend to tap into homophily and create overly homogeneous samples.

Diversity among participants in qualitative studies is not intended to be representative of the diversity occurring in the population. Instead, heterogeneity among participants is intended to provide breadth in the perspectives shared, as a complement to depth in the data collected.

Participant Recruitment & Retention Reviewed & Expanded

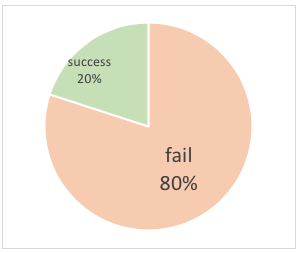

In our prior course you learned about the distinction between participant recruitment (individuals entering into a study) and participant retention (individuals remaining engaged with a longitudinal study over time). Intervention and evaluation research investigators need to have a strong recruitment and retention plan in place to ensure that the study can be successfully completed. Without the right numbers and types of study participants, even the best designed studies are doomed to failure: over 80% of clinical trials in medicine fail due to under-enrollment of qualified participants (Thomson CenterWatch, 2006)! How suitably this figure represents what happens in behavioral and social work intervention research is unknown (Begun, Berger, & Otto-Salaj, 2018). In fact, several authors have recommended having study personnel assigned specifically to the tasks of implementing a detailed participant recruitment and retention plan over the lifetime of the intervention or evaluation study (Begun, Berger, & Otto-Salaj, 2018; Jimenez & Czaja, 2016).

Here is a brief review of some of those principles and elaboration of several points relevant to intervention and evaluation research.

Participant recruitment.

Investigators are notorious for over-estimating the numbers of participants that are available, eligible, and willing to participate in their studies, particularly intervention studies (Thoma et al., 2010). This principle has been nicknamed Lasagna’s Law after the scientist Louis Lasagna who first described this phenomenon:

“Investigators all too often commit the error of (grossly) overestimating the pool of potential study participants who meet a study’s inclusion criteria and the number they can successfully recruit into the study” (Begun, Berger, & Otto-Salaj, p. 10).

You may recall learning in our prior course about a 3-step process related to participant recruitment (adapted from Begun, Berger, & Otto-Salaj, 2018): generating contacts, screening, and consent.

Generating contacts.

The first step involved generating initial contacts, soliciting interest from potential participants. Important considerations included the media applied (e.g., newsletter announcements, radio and television advertising, mail, email, social media, flyers, posters, and others) and the nature of the message inviting participation. Remember that recruitment messages are invitations to become a participant and need to respond to:

- why someone might wish to engage in the study

- need for details to make an informed choice about volunteering

- how they can become involved

- cultural relevance of the invitation message.

One strong motivation for individuals to participate in intervention research is the potential for receiving a new form of intervention, one to which they might not otherwise have access. This might be particularly motivating for someone who has been dissatisfied with other intervention options. The experimental option might seem desirable because it is different from something that has not worked well for them in the past, it seems more relevant, it is more practical/feasible than other options, or they were not good candidates for other options.

On the other hand, one barrier to participation is the experimental, unknown nature of the intervention—the need to conduct the study suggests that the outcomes are somewhat uncertain, and this may include unknown side effects. This barrier might easily outweigh the influence of a different motivation: the altruistic desire to contribute to something that might help others. Altruism is sometimes a motivation to engage in research but cannot be relied on alone to motivate participation in studies with long-term or intensive commitments of time and effort. It may be sufficient to motivate participation in an evaluation for interventions that are part of their service or treatment plan, however.

Screening.

Screening is part of the intervention research recruitment process. Intervention and evaluation research typically require participants to meet specific study criteria—inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria. These criteria might relate to their condition or problem, their past or present involvement in services or treatment, or specific demographic criteria (e.g., age, ethnicity, income level, gender identity, sexual orientation, or others). For example, inclusion criteria for a study might specify including only persons meeting the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for a substance use disorder. Exclusion criteria for that same study might specify excluding all persons with additional DSM-5 diagnoses such as schizophrenia or dementia unrelated to substance use and withdrawal.

Study investigators need to establish clear and consistent screening protocols for determining who meets inclusion/exclusion criteria for participation. Screening might include answers to simple questions, such as “Are you over the age of 18?” or “Are you currently pregnant?” Screening might also include administering one or more standardized screening instruments, such as the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT), the Patient Health Questionnaire screening for depression, the mini mental state examination (MMSE) screening for possible dementia, or the Hurt, Insult, Threaten, Scream (HITS) screening for intimate partner violence.

Regardless of the tool, screening information is not data since screening occurs prior to participant consent. The sole purpose of screening is to determine whether a potential volunteer is eligible to become a study participant. Ethically, screening protocols also need to include a strategy for referring persons who made an effort to participate in the intervention (expressed a need for intervention) but could not meet the inclusion criteria. In other words, if the door into the study is closed to them, alternatives need to be provided.

Consent.

Informed consent is the third phase of the recruitment process. You learned in our prior work what is required for informed consent. For intervention research with a generalizability aim the consent process should be reviewed by an Institutional Review Board (IRB). Evaluation research, on the other hand, that is to be used primarily to inform the practitioner, program, agency, or institution might not require IRB review. However, the agency should secure consent to participate in the evaluation, particularly if any activities involved fall outside of routine practice and record-keeping.

Important to keep in mind throughout the three phases of recruitment is that all three phases and what transpires during intervention relate to participant retention over the course of a longitudinal study. While it is critical during recruitment to consider, from the participants’ point-of-view, why they might wish to become involved in an intervention or evaluation study, in longitudinal studies it is equally important to consider why they might wish to continue to be involved over time. This topic warrants further attention.

Participant retention.

A great deal of resources and effort devoted to participant recruitment and delivering interventions is wasted each time a study participant drops out before the end of a study (called study attrition, this is the opposite of retention). Furthermore, the integrity of study conclusions can be jeopardized when study attrition occurs. An interesting meta-analysis was conducted to assess the potential impact on longitudinal studies of our nation’s high rates of incarceration, especially in light of extreme racial disparities in incarceration rates (Wang, Aminawung, Wildeman, Ross, & Krumholz, 2014). The investigators combined the samples from 14 studies into a complete sample of 72,000 study participants. Based on U.S. incarceration rates, they determined that longitudinal studies stand to lose up to 65% of black men from their samples. Under these conditions, study results and generalizability conclusions are potentially seriously impaired, especially since participant attrition is not occurring in a random fashion equivalently across all groups.

Relationship & Retention.

As previously noted, a major factor influencing participants’ willingness to remain engaged with an intervention or evaluation study over time is the nature of their experiences with the study. An important consideration for intervention and evaluation researchers is how they might reduce or eliminate barriers and inconveniences associated with participation in their studies (Jimenez & Czaja, 2016). These might include transportation, time, schedule, child care, and other practical concerns. Another factor influencing potential participants’ decisions to commit to engaging with a study concerns stigma—the extent to which they are comfortable becoming identified as a member of the group being served. Consider, for example, the potential stigma associated with being diagnosed with a mental illness, identified as a victim of sexual assault, or categorized as “poor,” or labeled with a criminal record. Strategies for minimizing or eliminating the stigma associated with participation in deficit-defined study and emphasizing the strengths base would go a long way toward encouraging participation. For example, recruiting persons concerned about their own substance use patterns is very different from recruiting “addicts” (see Begun, 2016).

Before launching a new program or extending an existing program to a new population, social workers might solicit qualitative responses from potential participants, to determine how planned elements are likely to be experienced by future participants. This may be performed as a preliminary focus group session where the group provides feedback and insight concerning elements of the planned intervention. Or, it may be conducted as a series of interviews or open-ended surveys with representatives of the population expected to be engaged in the intervention. Similarly, investigators sometimes conduct these preliminary studies with potential participants concerning the planned research activities, not only the planned intervention elements.

Two examples of focus groups assisting in the planning or evaluation of interventions come from Milwaukee County. HEART to HEART was a community-based intervention research project designed to reduce the risk of HIV exposure among women at risk of exposure by virtue of their involvement in risky sexual and/or substance use behavior. Women were to be randomly assigned to a preventive intervention protocol (combined brief HIV and alcohol misuse counseling) or a “control” condition (educational information provided about risk behaviors). Focus group members helped plan the name of the program, its identity and branding, many of the program elements, and the research procedures to ensure that it was culturally responsive, appropriate, and welcoming. Features such as conducting the work in a non-stigmatizing environment (a general wellness setting rather than a treatment center), creating a welcoming environment, gender and ethnic relevant materials, and providing healthful snacks were considered strong contributors to the women’s ongoing participation in the longitudinal study (Begun, Berger, & Otto-Salaj, 2018).

In a different intervention research project, a focus group was conducted with partners of men engaged in a batterer treatment program. The purpose of the focus group was to develop procedures for safely collecting evaluation data from and providing research incentive payments to the women at risk of intimate partner violence. The planned research concerned the women’s perceptions of their partners’ readiness to change the violent behavior, and investigators were concerned that some partners might respond abusively to a woman’s involvement in such a study. The women helped develop protocols for the research team to follow in communicating safely with future study participants and for materials future participants could use in safely managing their study participation (Begun, Berger, & Otto-Salaj, 2018).

Random Assignment Issues

First, it is essential to remember that random selection into a sample is very different from the process of randomization or random assignment to experimental conditions.

Random selection refers to the way investigators generate a study sample that is reflective and representative of the larger population to which the study results are going to be generalized (external validity)…Random assignment, often colloquially called randomization, has a different goal and is used at a different point in the intervention research process. Once we have begun to randomly select our participants, our study design might call for us to assign these recruited individuals to experience different intervention conditions” (Begun, Berger, & Otto-Salaj, 2018, p. 17-18).

Several study designs examined in Chapter 3 of this module involved random assignment of participants to one or another experimental condition. The purpose of random assignment is to improve the ability to attribute any observed group differences in the outcome data to the groups rather than to pre-existing differences among group members (internal validity). For example, if we were comparing individuals who received a novel intervention with those who received a treatment as usual (TAU) condition we would be in trouble if there happened to be more women in the novel treatment group and more men in the TAU group. We would not know if differences observed at the end were attributable to the intervention or if they were a function of gender instead.

Consider, for example, the random controlled trial (RCT) design from an intervention study to prevent childhood bullying (Jenson et al, 2010). A total of 28 elementary schools participated in this study, with 14 having been randomly assigned to the experimental condition (the new intervention) and 14 to the no-treatment control group. This allowed investigators to compare outcomes of the two treatment conditions with considerable confidence that the observed differences were attributable to the intervention; however, they were somewhat unlucky in their randomization effort since a greater percentage of children in the experimental condition were Latino/Latina than in the control condition. This ethnicity factor needs to be taken into consideration in conclusions about the observed significant reduction in bully victimization among students in the experimental schools compared to the control group.

Random assignment success & failure.

Randomly assigning participants to different experimental or intervention conditions requires investigators to introduce chance to the process. Randomness means a lack of systematic assignment. So, if you were to alternately assign participants to one condition or the other based alternating how each enrolled for the study a certain degree of chance is invoked: persons 1, 3, 5, 7 and so forth=control group, persons 2, 4, 6, 8 and so forth=experimental group. This system is only good if there is nothing systematic about how they were accepted into the study—nothing alphabetical or gendered or otherwise nonrandom. Systems of chance include lottery, roll of the dice, playing card draws, or use of a random numbers table—the same kinds of systems you read about in our prior course when we discussed how individuals might be randomly selected for participation in the sample. What could possibly go wrong?

Unfortunately, relying on chance does mean that random assignment (randomization) may fail to result in a balanced distribution of participants based on their characteristics even if the size of different assigned groups is even. This unfortunate luck was evident in the Jenson et al (2010) study previously mentioned where the distribution of Latino/Latina students was disproportionate in the two intervention condition groups. However, those investigators were only unlucky on this one dimension—there was reasonable comparability on a host of other variables.

Another way that random assignment sometimes goes wrong is through failure to stick to the rules of the randomization plan. Perhaps a practitioner really wants a particular client to experience the novel intervention (or the client threatens to participate only if assigned to that group). Suppose the practitioner somehow manipulates the individual’s assignment with the intent to replace that person with another individual so the numbers assigned to each group even out. Unfortunately, the result is reduced integrity of the overall study design—those individuals’ assignments not being random means that systematic assignment has crept into the study, jeopardizing study conclusions. “Randomization ensures that each patient has an equal chance of receiving any of the treatments under study” and generates comparable groups “which are alike in all the important aspects” with the notable exception of which intervention the groups receive (Suresh, 2011, p. 8). In reality, investigators, practitioners, and participants may be tempted to “cheat” chance to achieve a hoped-for assignment.

Assessing randomization results.

Investigators need to determine the degree to which their random assignment or randomization efforts were successful in creating equivalent groups. To do this they often turn to the kinds of statistical analyses you learned about in our prior course: chi-square, independent samples t-test, or analysis of variance (Anova), depending on the nature of the variables involved. The major difference here, compared to the analyses we previously practiced, is what an investigator hopes the result of the analysis will be. Here is the logic explained:

- the null hypothesis (Ho) is no difference exists between the groups.

- if the groups are equivalent, the investigator would find no difference.

- the investigator hopes not to find a difference—this does not guarantee that the groups are the same, only that no difference was observed.

To refresh your memory of how to work with these three types of analyses and to make them relevant to the question of how well randomization worked, we have three exercises in our Excel workbook.

Interactive Excel Workbook Activities

Complete the following Workbook Activities:

Chapter Summary

In this chapter you reviewed several concepts related to samples, sampling, and participant recruitment explored in our prior course. The sample size topic was expanded to address how sample size relates to effect size in intervention and evaluation research. Issues related to participant recruitment were reviewed, particularly as they relate to the need for engaging a diverse and representative sample of study participants and how these concerns relate to a study’s external validity. This topic was expanded into a 3-phase model of recruitment processes: generating contacts, screening volunteers for eligibility, and consenting participants. You then read about issues concerning participant retention over time in longitudinal intervention and evaluation studies, especially the importance of participants’ experiences and relationships with the study. This included a discussion of participants’ experiences with random assignment to study conditions, depending on the study design, and how randomization might or might not work. You learned a bit about how to assess the adequacy of the randomization effort in our Excel exercises and to think about how randomization successes and failures might affect a studies integrity and internal validity.

Stop and Think

Take a moment to complete the following activity.

Take a moment to complete the following activity.