Module 2 Chapter 2: The Link Between Theory, Research, and Social Justice

Theory has been mentioned several times in Chapter 1 discussions. In this chapter, we explore the relationship between theory and research, paying particular attention to how theory and research relate to promoting social justice.

In this chapter you will read about:

- Why theory matters to social work

- How theory and research relate to social justice

The Significance of Theory

It is helpful to begin with thinking about what theory is. Theory is defined as a belief, idea, or set of principles that explain something—the set of principles may be organized in a complex manner or may be quite simple in nature. Theories are not facts; they are conjectures and predictions that need to be tested for their goodness-of-fit with reality. A scientific theory is an explanation supported by empirical evidence. Therefore, scientific theory is based on careful, reasonable examination of facts, and theories are tested and confirmed for their ability to explain and predict the phenomena of interest.

Theory is central to the development of social work interventions, as it determines the nature of our solutions to identified problems. Consider an example whereby programmatic and social policy responses might be influenced by the way that a problem like teen pregnancy is defined and the theories about the problem. In Table 2-1 you can see different definitions or theories of the problem on the left, and the logical responses on the right. In many cases, the boxes on the right can also be supplemented with content from other boxes addressing other problem definitions or theories.

Table 2-1. Analysis of teen pregnancy: How defining a problem determines responses

| Problem definition/theory | Policy response option |

|---|---|

| Teen pregnancy is not a problem | No need to respond |

| Teen girls are having sex | Keep them otherwise occupied allowing no opportunity; keep them separated from potential sex partners (including sexual abuse); teach/preach "Just Say No!" |

| Teen girls are getting pregnant | Make birth control available, accessible, affordable, and palatable; keep them separated from boys and men capable of impregnating them (including sexual abuse) |

| Teen girls are having babies | Terminate teen pregnancies; prevent pregnancy—see above |

| Babies born to teen mothers are less healthy | Provide resources for healthy prenatal development; prevent pregnancy/having babies—see above |

| Teen mothers have poorer health than other teens, other mothers | Provide health-promoting resources to teen mothers; prevent pregnancy/having babies—see above |

| Teen mothers are raising babies inadequately | Provide resources to promote positive parenting by teen mothers (or all parents); place babies with other parents (other family members or foster/adoptive families); prevent pregnancy/having babies—see above |

| Being a teen mother interrupts her education and future employability/income potential | Provide resources to promote positive educational and vocational/income producing outcomes for teen mothers; prevent teen mothers raising babies, prevent pregnancy/having babies—see above |

Hopefully, through this example, you can see how the way we define a problem and our theories about its causes determines the types of solutions we develop. Solutions are also dependent on whether they are feasible, practical, reasonable, ethical, culturally appropriate, and politically acceptable.

Theory, Research, and Social Justice

Theory is integral to research and research is integral to theory. Theory guides the development of many research questions and research helps generate new theories, as well as determining whether support for theories exists. What is important to remember is that theory is not fact: it is a belief about how things work; theory is a belief or "best guess" that awaits the support of empirical evidence.

"The best theories are those that have been substantiated or validated in the real world by research studies" (Dudley, 2011, p. 6).

Countless theories exist, and some are more well-developed and well-defined than others. More mature theories have had more time and effort devoted to supporting research, newer theories may be more tentative as supporting evidence is being developed. Theories are sometimes disproven and need to be scrapped completely or heavily overhauled as new research evidence emerges. And, exploratory research leads to the birth of new theories as new phenomena and questions arise, or as practitioners discover ways that existing theory does not fit reality.

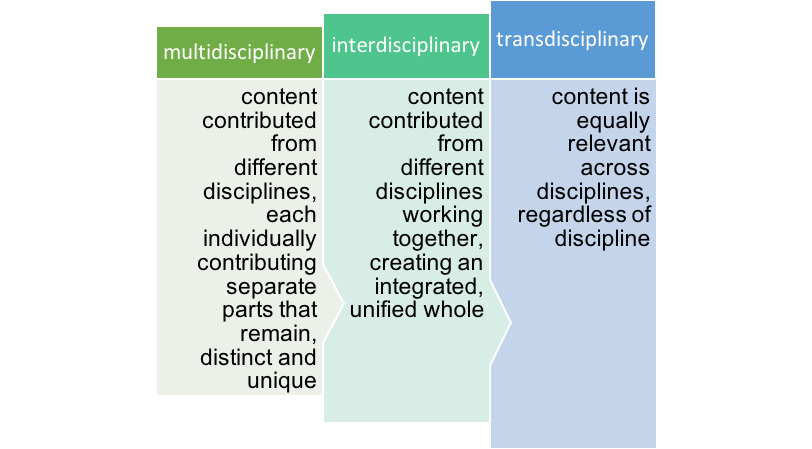

Examples of theories and theoretical models with which you may have become familiar in other coursework are developed, tested, and applied in research from multiple disciplines, including social work. You may be familiar with the concepts of multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary practice, research and theory, but you also might be interested to learn the concept of transdisciplinary research and theory. The social work profession engages in all three, as described in Figure 2-1.

Figure 2-1. Comparison of multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, and transdisciplinary as concepts

An example of transdisciplinarity is demonstrated in motivational interviewing. The principles and practice of motivational interviewing skills transcends disciplines—it is relevant and effective regardless of a practitioner's discipline and regardless of which discipline is conducting research that provides supporting evidence. An example of interdisciplinarity is when social workers, nurses, pediatricians, occupational therapists, respiratory therapists, and physical therapists work together to create a system for reducing infants' and young children's environmental exposure to heavy metal contamination in their home, childcare, recreational, food and water (e.g., lead and mercury). An example of multidisciplinarity is when a pediatrician, nurse, occupational therapist, social worker, and physical therapist each deliver discipline-specific services to children with intellectual disabilities.

Here are examples of theories that you may have encountered or eventually will encounter in your career:

- behavioral theory

- cognitive theory

- conflict theory

- contact theory (groups)

- critical race theory

- developmental theory (families)

- developmental theory (individuals)

- feminist theory

- health beliefs model

- information processing theory

- learning theory

- lifecourse or lifespan theory

- neurobiology theories

- organizational theory

- psychoanalytic theory

- role theory

- social capital model

- social ecological theory

- social learning theory

- social network theory

- stress vulnerability model

- systems theory

- theory of reasoned action/planned behavior

- transtheoretical model of behavior change

Social work practitioners generate new theories in the field all the time, but these theories are rarely documented or systematicallyl tested. Applying systematic research methods to test these practice-generated theories can help expand the social work knowledge base. Well-developed theories must be testable through the application of research methods. Furthermore, they both supplement and complement other theories that have the support of strong evidence behind them. In addition to these points, for theories to be relevant to social work, they need to:

- have practice implications at one or more level of intervention—suggest principles of action;

- be responsive to human diversity;

- contribute to the promotion of social justice (Dudley, 2011).

Social Justice and The Grand Challenges for Social Work. In 2016, the American Academy of Social Work & Social Welfare (AASWSW) rolled out a set of 12 initiatives, challenging the social work profession to develop strategies for having a significant impact on a broad set of problems challenging the nation: "their introduction truly has the potential to be a defining moment in the history of our profession" (Williams, 2016, p. 67). The Grand Challenges directly relate to content presented in the Preamble to the Code of Ethics of the National Association of Social Workers (2017):

The primary mission of the social work profession is to enhance human well-being and help meet the basic human needs of all people, with particular attention to the needs and empowerment of people who are vulnerable, oppressed, and living in poverty. A historic and defining feature of social work is the profession's dual focus on individual well-being in a social context and the well-being of society. Fundamental to social work is attention to the environmental forces that create, contribute to, and address problems in living (p. 1).

The ambitious Grand Challenges (http://aaswsw.org/grand-challenges-initiative/12-challenges/) call for a synthesis of research and evidence generating endeavors, social work education, and social work practice (at all levels), with promoting social justice and transforming society at the forefront of attention. None of the Grand Challenges can be achieved without collaboration between social work researchers, practitioners, key stakeholders/constituents, policy makers, and members of other professions and disciplines (see Table 2-2). Each of the papers published under the 12 umbrella challenges not only reviews evidence related to the challenge, but also identifies a research and action agenda for promoting change and achieving the stated challenge goals.

Table 2-2. 12 Grand Challenges for Social Work

| Grand Challenge | Topics Under the Challenges |

|---|---|

| Ensure healthy development for all youths |

|

| Close the health gap |

|

| Stop family violence |

|

| Advance long and productive lives |

|

| Eradicate social isolation |

|

| End homelessness |

|

| Create social responses to a changing environment |

|

| Harness technology for social good |

|

| Promote smart decarceration |

|

| Reduce extreme economic inequality |

|

| Build financial capability for all |

|

| Achieve equal opportunity and justice |

|

Theory and its related research is presented in the literature of social work and other disciplines. Being able to locate the relevant literature is an important skill for social work professionals and researchers to master. The next chapter introduces some basic principles about identifying literature that informs us about theory and the research that leads to the development of new theories and the testing of existing theories.

Using Data to Support Social Justice Advocacy

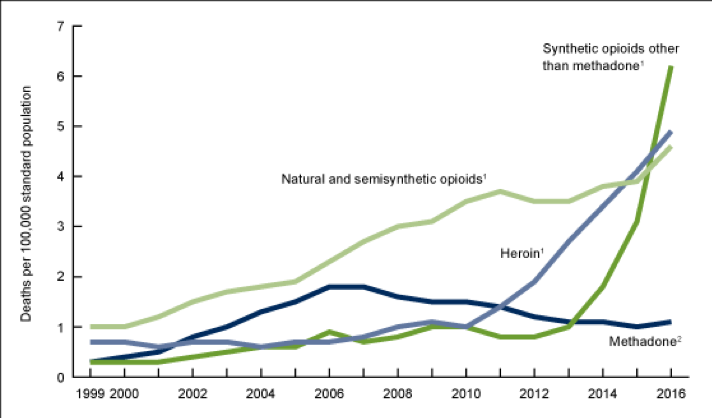

It is one thing to collect data, statistics, and information about the dimensions of a social problem; it is another to apply those data, statistics, and information in action to promote social change around an identified social justice cause. Advocacy is one tool or role important to the social work profession since its earliest days. Data and empirical evidence should routinely support social workers' social justice advocacy efforts at the micro level—when working with specific client systems (case advocacy). Social justice advocacy also is a macro-level practice (cause advocacy), one that often involves the use of data to raise awareness about a cause, establish change goals, and evaluate the impact of change efforts. Consider, for example, the impact of data on social justice advocacy related to opioid misuse and addiction across the United States. Data regarding the sharp, upward trend in opioid-related deaths have had a powerful impact on public awareness, having captivated the attention of mass media outlets. These are data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for the period 1999 to 2016 (see Figure 2-2). The death rate from opioid overdose increased remarkably in the most recent years depicted, including heroin, natural and semisynthetic (morphine, codeine, hydrocodone, oxycodone), and synthetic opioids (fentanyl, fentanyl analogs, tramadol); the rate declined somewhat for deaths related to methadone, a highly controlled prescription medication used to treat opioid addiction (Hedegaard, Warner, & Miniño, 2017). In 2016 the overdose death rate was more than triple the 1999 rate and surpassed all other causes of death (including homicide and automobile crashes) for persons aged 50 or younger (Vestal, 2018). The good news is that the rates dropped significantly across 14 states during 2017 as new policy approaches were implemented—including more widespread use and access to naloxone (an opioid overdose reversal drug). The bad news is that the opioid overdose death rates increased significantly across 5 states and the District of Columbia as fentanyl and related drugs became integrated into the illicit drug supply: "Nationally, the death toll is still rising" (Vestal, 2018, p. 1). The Ohio Department of Health, with Ohio being one of the 5 states with more than a 30% increase in opioid overdose deaths, now recommends that naloxone be used more widely in overdose situations, whether or not opioids are known to be involved.

Figure 2-2. Opioid drug overdose death rate trends 1999-2016, by opioid category

Having data of this sort available to argue the urgency of a cause is of tremendous value. Imagine the potential impact of data on social issues such as child maltreatment, intimate partner violence, human trafficking, and death by suicide. Imagine also the potential impact of data concerning disparities in health, incarceration, mental and traumatic stress disorders, and educational or employment achievement across members of different racial/ethnic, age, economic, and national origin groups. This type of evidence has the potential to be a powerful element in the practice of social justice advocacy.

Follow links below to specific AASWSW Grand Challenges and consider the ways that research evidence is being used to advocate for at least one of the following social justice causes:

- Health Equity: Eradicating Health Inequalities for Future Generations

- From Mass Incarceration to Smart Decarceration

- Safe Children: Reducing Severe and Fatal Maltreatment

- Ending Gender Based Violence: A Grand Challenge for Social Work

- Prevention of Schizophrenia and Severe Mental Illness

- Increasing Productive Engagement in Later Life

- Strengthening the Social Responses to the Human Impacts of Environmental Change