Module 3 Chapter 1: From Research Questions to Research Approaches

The approaches that social work investigators adopt in their research studies are directly related to the nature of the research questions being addressed.In Module 2 you learned about exploratory, descriptive, and explanatory research questions. Let’s consider different approaches to finding answers to each type of question.

In this chapter we build on what was learned in Module 2 about research questions, examining how investigators’ approaches to research are determined by the nature of those questions. The approaches we explore are all systematic, scientific approaches, and when properly conducted and reported, they all contribute empirical evidence to build knowledge. In this chapter you will read about:

- qualitative research approaches for understanding diverse populations, social problems, and social phenomena,

- quantitative research approaches for understanding diverse populations, social problems, and social phenomena,

- mixed methods research approaches for understanding diverse populations, social problems, and social phenomena.

Overview of Qualitative Approaches

Questions of a descriptive or exploratory nature are often asked and addressed through qualitative research. The specific aim in these studies is to understand diverse populations, social work problems, or social phenomena as they naturally occur, situated in their natural environments, providing rich, in-depth, participant-centered descriptions of the phenomena being studied. Qualitative research approaches have been described as “humanistic” in aiming to study the world from the perspective of those who are experiencing it themselves; this also contributes to a social justice commitment in that the approaches give “voice” to the individuals who are experiencing the phenomena of interest (Denzen & Lincoln, 2011). As such, qualitative research approaches are also credited with being sensitive and responsive to diversity—embracing feminist, ethnic, class, critical race, queer, and ability/disability theory and lenses.

In qualitative research, the investigator is engaged as an observer and interpreter, being acutely aware of the subjectivity of the resulting observations and interpretations.

“At this level, qualitative research involves an interpretive, naturalistic approach to the world” (Denzin & Lincoln, 2011, p. 3)

Because the data are rich and deep, a lot of information is collected by involving relatively few participants; otherwise, the investigator would be overwhelmed by a tremendous volume of information to collect, sift through, process, interpret, and analyze. Thus, a single qualitative study has a relatively low level of generalizability to the population as a whole because of its methodology, but that is not the aim or goal of this approach.

In addition, because the aim is to develop understanding of the participating individuals’ lived experiences, the investigator in a qualitative study seldom imposes structure with standardized measurement tools. The investigator may not even start with preconceived theory and hypotheses. Instead, the methodologies involve a great deal of open-ended triggers, questions, or stimuli to be interpreted by the persons providing insight:

“Qualitative research’s express purpose is to produce descriptive data in an individual’s own written or spoken words and/or observable behavior” (Holosko, 2006, p. 12).

Furthermore, investigators often become a part of the qualitative research process: they maintain awareness of their own influences on the data being collected and on the impact of their own experiences and processes in interpreting the data provided by participants. In some qualitative methodologies, the investigator actually enters into/becomes immersed in the events or phenomena being studied, to both live and observe the experiences first-hand.

Qualitative data and interpretations are recognized as being subjective in nature—that is the purpose—rather than assuming objectivity. Qualitative research is based on experientially derived data and is interpretive, meaning it is “concerned with understanding the meaning of human experience from the subject’s own frame of reference” (Holosko, 2006, p. 13). In this approach, conclusions about the nature of reality are specific to each individual study participant, following his or her own interpretation of that reality. These approaches are considered to flow from an inductive reasoning process where specific themes or patterns are derived from general data (Creswell & Poth, 2018).

Several purposes of qualitative approaches in social work include:

- describing and exploring the nature of phenomena, events, or relationships at any system level (individual to global)

- generating theory

- initially test ideas or assumptions (in theory or about practices)

- evaluate participants’ lived experiences with practices, programs, policies, or participation in a research study, particularly with diverse participants

- explore “fit” of quantitative research conclusions with participants’ lived experiences, particularly with diverse participants

- inform the development of clinical or research assessment/measurement tools, particularly with diverse participants.

Overview of Quantitative Approaches

Questions of the exploratory, descriptive, or explanatory type are often asked and addressed through quantitative research approaches, particularly questions that have a numeric component. Exploratory and descriptive quantitative studies rely on objective measures for data collection which is a major difference from qualitative studies which are aimed at understanding subjective perspectives and experiences. Explanatory quantitative studies often begin with theory and hypotheses, and proceed to empirically test the hypotheses that investigators generated. By their quantitative (numeric) nature, statistical hypothesis testing is possible in many types of quantitative studies.

Quantitative research studies utilize methodologies that enhance generalizability of results to the greatest extent possible—individual differences are de-emphasized, similarities across individuals are emphasized. These studies can be quite large in terms of participant numbers, and the study samples need to be developed in such a manner as to support generalization to the larger populations of interest.

The process is generally described as following a deductive logical system where specific data points are combined to lead to developing a generalizable conclusion. The philosophical roots (epistemology) underlying quantitative approaches is positivism, involving the seeking of empirical “facts or causes of social phenomena based on experimentallyderived evidence and/or valid observations” (Holosko, 2006, p. 13). The empirical orientation is objective in that investigators attempt to be detached from the collection and interpretation of data in order to minimize their own influences and biases. Furthermore, investigators utilize objective measurement tools to the greatest extent possible in the process of collecting quantitative study data.

Several purposes of quantitative approaches in social work include:

- describing and exploring the dimensions of diverse populations, phenomena, events, or relationships at any system level (individual to global)—how much, how many, how large, how often, etc. (including epidemiology questions and methods)

- testing theory (including etiology questions)

- experimentally determining the existence of relationships between factors that might influence phenomena or relationships at any system level (including epidemiology and etiology questions)

- testing causal pathways between factors that might influence phenomena or relationships at any system level (including etiology questions)

- evaluate quantifiable outcomes of practices, programs, or policies

- assess the reliability and validity of clinical or research assessment/measurement tools.

Overview of Mixed-Method Approaches

Important dimensions distinguish between qualitative and quantitative approaches. First, qualitative approaches rely on “insider” perspectives, whereas quantitative approaches are directed by “outsiders” in the role of investigator (Padgett, 2008). Second, qualitative results are presented holistically, whereas quantitative approaches present results in terms of specific variables dissected from the whole for close examination; qualitative studies emphasize the context of individuals’ experiences, whereas quantitative studies tend to decontextualize the phenomena under study (Padgett, 2008). Third, quantitative research approaches tend to follow a positivist philosophy, seeking objectivity and representation of what actually exists; qualitative research approaches follow from a post-positivist philosophy, recognizing that observation is always shaped by the observer, therefore is always subjective in nature and this should be acknowledged and embraced. In post-positivist qualitative research traditions, realities are perceived as being socially constructed, whereas in positivist quantitative research, a single reality exists, waiting to be discovered or understood. The quantitative perspective on reality has a long tradition in the physical and natural sciences (physics, chemistry, anatomy, physiology, astronomy, and others). The social construction perspective has a strong hold in social science and understanding social phenomena. But what if an investigator’s questions are relevant to both qualitative and quantitative approaches?

Given the fundamental philosophical and practical differences, some scholars argue that there can be no mixing of the approaches, that the underlying paradigms are too different. However, mixed-methods research has also been described as a new paradigm (since the 1980s) for social science:

“Like the mythology of the phoenix, mixed methods research has arisen out of the ashes of the paradigm wars to become the third methodological movement. The fields of applied social science and evaluation are among those which have shown the greatest popularity and uptake of mixed methods research designs” (Cameron & Miller, 2007, p. 3).

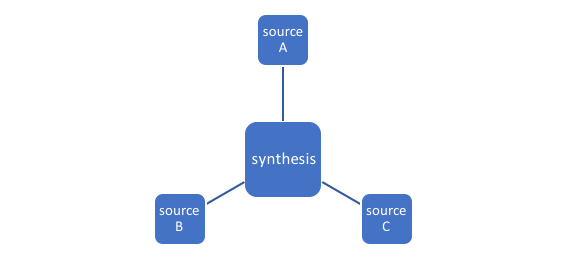

Mixed-methods research approaches are used to address in a single study the acknowledged limitations of both quantitative and qualitative approaches. Mixed methods research combines elements of both qualitative and quantitative approaches for the purpose of achieving both depth and breadth of understanding, along with corroboration of results (Johnson, Onwuegbuzie, & Turner, 2007, p. 123). One mixed-methods strategy is related to the concept of triangulation: understanding an event or phenomenon from the use of varied data sources and methods all applied to understanding the same phenomenon (Denzin & Lincoln, 2011; see Figure 1-1).

Figure 1-1. Depiction of triangulation as synthesis of different data sources

For example, in a survey research study of student debt load experienced by social work doctoral students, the investigators gathered quantitative data concerning demographics, dollar amounts of debt and resources, and other numeric data from students and programs (Begun & Carter, 2017). In addition, they collected qualitative data about the experience of incurring and managing debt load, how debt shaped students’ career path decisions, practices around mentoring doctoral students about student debt load, and ideas for addressing the problem. Triangulation came into play in two ways: first, collecting data from students and programs about the topics, and second, a sub-sample of the original surveyed participants engaged in qualitative interviews concerning the “fit” or validity of conclusions drawn from the prior qualitative and quantitative data.

Three different types of mixed methods approaches are used:

- Convergent designs involve the simultaneous collection of both qualitative and quantitative data, followed by analysis of both data sets, and merging the two sets of results in a comparative manner.

- Explanatory sequential designs use quantitative methods first, and then apply qualitative methods to help explain and further interpret the quantitative results.

- Exploratory sequential designs first explore a problem or phenomenon through qualitative methods, especially if the topic is previously unknown or the population is understudied and unfamiliar. These qualitative findings are then used to build the quantitative phase of a project (Creswell, 2014, p. 6).

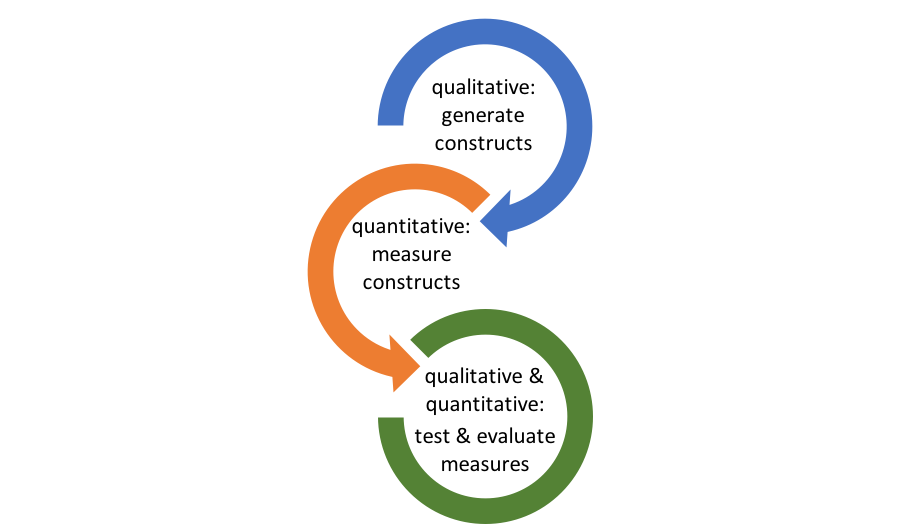

Mixed methods approaches are useful in developing and testing new research or clinical measurement tools. For example, this is done in an exploratory sequential process whereby detail-rich qualitative data inform the creation of a quantitative instrument. The quantitative instrument is then tested in both quantitative and qualitative ways to confirm that it is adequate for its intended use. This iterative process is depicted in Figure 1-2.

Figure 1-2. Iterative qualitative and quantitative process of instrument development

One example of how this mixed-methods approach was utilized was in development of the Safe-At-Home instrument for assessing individuals’ subjective readiness to change their intimate partner violence behavior (Begun et al., 2003; 2008). The transtheoretical model of behavior change (TMBC) underlies the instrument’s development: identifying stages in readiness to change one’s behavior and matching these stages to the most appropriate type of intervention strategy (Begun et al., 2001). The first step in developing the intimate partner violence Safe-At-Home instrument for assessing readiness to change was to qualitatively generate a list of statements that could be used in a quantitative rating scale. Providers of treatment services to individuals arrested for domestic or relationship violence were engaged in mutual teaching/learning with the investigators concerning the TMBC as it might relate to the perpetration of intimate partner violence. They independently generated lists of the kinds of statements they heard from individuals in their treatment programs, statements they believed were demonstrative of what they understood as the different stages in the change process. The investigators then worked with them to reduce the amassed list of statements into stage-representative categories, eliminating duplicates and ambiguous statements, and retaining the original words and phrases they heard to the greatest extent possible. The second phase was both quantitative and qualitative in nature: testing the instrument with a small sample of men engaged in batters’ treatment programs and interviewing the men about the experience of using the instrument. Based on the results and their feedback, the instrument was revised. This process was followed through several iterations. The next phases were quantitative: determining the psychometric characteristics of the instrument and using it to quantitatively evaluate batterer treatment programs—the extent to which individuals were helped to move forward in stages of the change cycle.

Interactive Excel Workbook Activities

Complete the following Workbook Activity:

Chapter Summary

In this chapter you were introduced to three general approaches for moving from research question to research method. You were provided with a brief overview of the philosophical underpinnings and uses of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods approaches. Next, you are provided with more detailed descriptions of qualitative and quantitative traditions and their associated methodologies.

Take a moment to complete the following activity.