Module 10: Stimulant Substances

Ch. 1: Introduction

The first reading for Module 10 presents information about stimulant substances, the epidemiology of stimulant drug use, and the effects of these substances on human bodies and behavior. This topic overlaps to some extent with our discussion of prescription drug abuse to come in Module 13. However, there are many forms of stimulant substances: some are completely legal and unregulated (like coffee and tea), others are semi-regulated (like age restrictions on tobacco products and products requiring a prescription), and some are highly regulated (illegal to manufacture/distribute or possess without a prescription, like methamphetamine). In this way, Module 10 overlaps with the Schedule of Drugs content presented in your Module 9 lecture content.

In this first chapter you will read about:

- The general class of stimulant substances

- Why stimulants might be used in treating attention deficit disorder (ADD) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- Epidemiological patterns in the use of amphetamines, methamphetamine, cocaine, tobacco, and caffeinated beverages

- Key terms related to the class of stimulant substances.

Introduction to Stimulant Substances

Stimulant substances are generally those with psychoactive effects of increasing alertness, attentiveness/attention, and energy level. Some of these substances are naturally occurring, while others are manufactured or synthetic. Amphetamines are synthetic drugs that affect the levels of at least four major neurotransmitter systems in the human brain: serotonin, epinephrine, norepinephrine, and dopamine. You have been learning about these neurotransmitters throughout our course, especially in Module 3 and 4. Methamphetamine is a specific form of amphetamine. Cocaine is another stimulant substance, drawn from a naturally occurring source: erythroxylum plants (coca, laetevirens, or novogranatense variants).

Stimulant substances are generally those with psychoactive effects of increasing alertness, attentiveness/attention, and energy level. Some of these substances are naturally occurring, while others are manufactured or synthetic. Amphetamines are synthetic drugs that affect the levels of at least four major neurotransmitter systems in the human brain: serotonin, epinephrine, norepinephrine, and dopamine. You have been learning about these neurotransmitters throughout our course, especially in Module 3 and 4. Methamphetamine is a specific form of amphetamine. Cocaine is another stimulant substance, drawn from a naturally occurring source: erythroxylum plants (coca, laetevirens, or novogranatense variants).

It should not be surprising, therefore, to find that other types of plants also can have stimulant effects: tobacco leaves(nicotiana tabacum plants) and coffee beans (coffea plants), for example. Chocolate comes from yet another bean: that of the cacao or cocoa plant (theobroma cacao trees).

It should not be surprising, therefore, to find that other types of plants also can have stimulant effects: tobacco leaves(nicotiana tabacum plants) and coffee beans (coffea plants), for example. Chocolate comes from yet another bean: that of the cacao or cocoa plant (theobroma cacao trees).

Stimulant substances have been used medicinally for many generations and across many cultures. In the United States, stimulants have been prescribed to treat several conditions, including attention deficit disorder (ADD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), narcolepsy, some forms of depression, respiratory problems (including asthma), and as a weight management/weight loss aid.

Significant side effects are associated with the use of amphetamines and other stimulant substances, however. Addiction is one concern. For many of these substances, tolerance develops quickly so individuals use increasingly higher doses to experience the desired effects. Many people experience withdrawal symptoms when stimulants are discontinued: fatigue, depression, headaches, and disrupted sleep patterns are common.

Significant side effects are associated with the use of amphetamines and other stimulant substances, however. Addiction is one concern. For many of these substances, tolerance develops quickly so individuals use increasingly higher doses to experience the desired effects. Many people experience withdrawal symptoms when stimulants are discontinued: fatigue, depression, headaches, and disrupted sleep patterns are common.

Another possibility that individuals may experience when using stimulant substances (even as prescribed medications) is a significant change in psychological functioning. This might include feeling restless and jittery, mood swings, irritability, and paranoia. Sometimes psychosis is triggered by the use of stimulant drugs. These effects of stimulant “uppers” may lead a person to try using another class of substances to manage them—that would be the substances sometimes called “downers” (CNS depressants) that we studied in Module 9. The emotional effects of stimulant medication pharmacokinetics (rise and fall of levels circulating in the body) is also a reason for the development of extended release stimulant medications: for example, Ritalin® comes in an extended release formulation to even out the effects. Extended release forms of medications are intended to make the therapeutic effects last longer and taper off more gradually. Extreme emotional fluctuations are often experienced by individuals (especially children and adolescents) as a function of their medication blood levels dropping below a therapeutic threshold as the medications are broken down (metabolized) in the body over time—an experience called “crashing” is characterized by a sudden, intense drop in mood, tearfulness, increased symptoms of whatever is being treated with the medication, and sometimes early withdrawal symptoms.

Another possibility that individuals may experience when using stimulant substances (even as prescribed medications) is a significant change in psychological functioning. This might include feeling restless and jittery, mood swings, irritability, and paranoia. Sometimes psychosis is triggered by the use of stimulant drugs. These effects of stimulant “uppers” may lead a person to try using another class of substances to manage them—that would be the substances sometimes called “downers” (CNS depressants) that we studied in Module 9. The emotional effects of stimulant medication pharmacokinetics (rise and fall of levels circulating in the body) is also a reason for the development of extended release stimulant medications: for example, Ritalin® comes in an extended release formulation to even out the effects. Extended release forms of medications are intended to make the therapeutic effects last longer and taper off more gradually. Extreme emotional fluctuations are often experienced by individuals (especially children and adolescents) as a function of their medication blood levels dropping below a therapeutic threshold as the medications are broken down (metabolized) in the body over time—an experience called “crashing” is characterized by a sudden, intense drop in mood, tearfulness, increased symptoms of whatever is being treated with the medication, and sometimes early withdrawal symptoms.

There also are general physiological changes that come with using stimulant substances to consider. For example, these substances reduce appetite, increase heart rate, increase blood pressure, and increase body temperature for most people. This places increased risk of cardiac problems (irregular heartbeat, accelerated heart rate, heart attack), hyperthermia (overheating), and seizures on our list of concerns, along with malnutrition or otherwise unhealthy weigh loss. Children taking stimulant medications may be slow to grow and their progression into puberty may be delayed.

There also are general physiological changes that come with using stimulant substances to consider. For example, these substances reduce appetite, increase heart rate, increase blood pressure, and increase body temperature for most people. This places increased risk of cardiac problems (irregular heartbeat, accelerated heart rate, heart attack), hyperthermia (overheating), and seizures on our list of concerns, along with malnutrition or otherwise unhealthy weigh loss. Children taking stimulant medications may be slow to grow and their progression into puberty may be delayed.

Many of the experienced physiological symptoms are a result of stimulant substances on the human autonomic nervous system (ANS). This is the nervous system that manages autonomous (automatic) bodily functions—the ones that we do not have to consciously think about. This would be things like maintaining breathing, heartbeat, blood pressure, body temperature, sweating, digestion, and kidney/urinary functions. Two complementary divisions of the ANS allow regulation of body functions in response to internal changes or changes in the environment (this regulation we called homeostasis in our earlier modules). The sympathetic nervous system runs at a baseline level to help maintain homeostasis. In addition, this system can gear up to create a rapid “fight or flight” stress response to events or stimuli in the environment.

The parasympathetic nervous system helps bring the body back to its homeostatic resting baseline after arousal. What is the role of stimulant substances in all of this? Most of these substances stimulate the sympathetic nervous system as if there actually were an event warranting a “fight or flight” stress response. The way that these drugs affect the sympathetic nervous system is through their influence on the neurotransmitters epinephrine and norepinephrine. Norepinepherine, when acting as a neurotransmitter, is involved in promoting focused, “vigilent” concentration. This contributes to their often being misinterpreted as “intelligence” producing substances.

The parasympathetic nervous system helps bring the body back to its homeostatic resting baseline after arousal. What is the role of stimulant substances in all of this? Most of these substances stimulate the sympathetic nervous system as if there actually were an event warranting a “fight or flight” stress response. The way that these drugs affect the sympathetic nervous system is through their influence on the neurotransmitters epinephrine and norepinephrine. Norepinepherine, when acting as a neurotransmitter, is involved in promoting focused, “vigilent” concentration. This contributes to their often being misinterpreted as “intelligence” producing substances.

Why would we treat ADD or ADHD with stimulant medication? It seems rather paradoxical or counter-intuitive on the surface—a bit like pouring lighter fluid on an already burning fire. Medications like Ritalin®, Concerta®, Adderall®, and Dexedrine® work by increasing the dopamine levels in the brain. Dopamine is responsible for cognitive alertness. This dopamine release improves a person’s attention, motivation, and ability to focus. In turn, this directly helps people improve in a whole lot of performance areas, but it also helps more indirectly, as well.

Why would we treat ADD or ADHD with stimulant medication? It seems rather paradoxical or counter-intuitive on the surface—a bit like pouring lighter fluid on an already burning fire. Medications like Ritalin®, Concerta®, Adderall®, and Dexedrine® work by increasing the dopamine levels in the brain. Dopamine is responsible for cognitive alertness. This dopamine release improves a person’s attention, motivation, and ability to focus. In turn, this directly helps people improve in a whole lot of performance areas, but it also helps more indirectly, as well.

For example, it can improve a person’s ability to respond appropriately to social cues, ability to stay on task in school or work activities, ability to control impulsiveness, social relationships, self-esteem, self-confidence, and self-image. Medication alone is not sufficient to manage ADD or ADHD. A lot of hard work to learn coping and self-management skills is also necessary; the medication gives the person a chance for behavioral interventions to be effective. Without medication it is more difficult, but not impossible, for a person with ADD or ADHD to focus attention needed to learn these new intentional behaviors and skills.

For example, it can improve a person’s ability to respond appropriately to social cues, ability to stay on task in school or work activities, ability to control impulsiveness, social relationships, self-esteem, self-confidence, and self-image. Medication alone is not sufficient to manage ADD or ADHD. A lot of hard work to learn coping and self-management skills is also necessary; the medication gives the person a chance for behavioral interventions to be effective. Without medication it is more difficult, but not impossible, for a person with ADD or ADHD to focus attention needed to learn these new intentional behaviors and skills.

People vary widely in their level of response and improvement with this form of medication—some people improve dramatically, others only slightly, and some not at all. However, systematically tested evidence indicates that these performance improvement (cognitive enhancement) effects are not present in individuals who do not have ADD or ADHD—despite widespread popular beliefs (NIDA, 2014). Use of these drugs by this population can actually stimulate hyperactivity while the drug is in their systems. And, of great concern with this form of amphetamine prescription abuse: we have learned that substances with the effect of increasing dopamine also have an increased probability of addiction because of the drug’s effects on the pleasure centers of the brain.

Epidemiological Patterns

Because there are so many different types of stimulant substances to consider, we need to look at the data concerning their use patterns separately. The NSDUH data (SAMHSA, 2016) indicates that over 1.65 million individuals aged 12 and over misused stimulant drugs in the past month. While males (877,000) did outnumber females (776,000), the ratio by gender was not markedly different.

Think about it, Part 1: Before you read further, spend a moment making note of your own guesses about each of the following epidemiological patterns.

- Place these substances in the order you believe they fall from most to least commonly used by individuals in the United States: amphetamine prescription abuse, methamphetamine, cocaine, tobacco, and caffeinated beverages.

- For each substance, which gender do you think reports the highest rate of misuse?

- For each substance, which racial/ethnic group do you think reports the highest rate of misuse?

Amphetamines/Methylphenidate: The 2015 data indicate that just over 5 million persons aged 12 and older reported current or recent (past month) misuse of prescription amphetamines or methylphenidate (SAMHSA, 2016). Extrapolating from other proportions in the study, this translates to about 1.67% of the population studied. About 500,000 were adolescents aged 12-17 years. There were about 2.5 million in the 18-25 year age group and 2.2 million in the group aged 26 and older.

Methamphetamine: Almost 900,000 individuals (0.3%) aged 12 and over recently (past month) used methamphetamine according the 2015 NSDUH survey (SAMHSA, 2016). This most often was reported in large metropolitan areas (461,000) and least often in nonmetropolitan areas (160,000), with small metropolitan areas falling in between (276,000). Regionally, methamphetamine use was most common in the South (375,000) and West (358,000) of the United States and least common in the Midwest (102,000) and Northeast (62,000). Use by males was at a rate more than double that for females, and the largest group using methamphetamine was white.

Cocaine: Looking at the 2015 NSDUH data (SAMHSA, 2016) we can see that an estimated 1.88 million persons (0.7%) aged 12 and over engaged in current or recent (past month) use of cocaine. Twice as many were males compared to females in this group, with the most common racial/ethnic group being white (not Hispanic or Latino), and the largest group being employed full-time. Crack cocaine use was relatively uncommon (394,000) among those aged 12 and over.

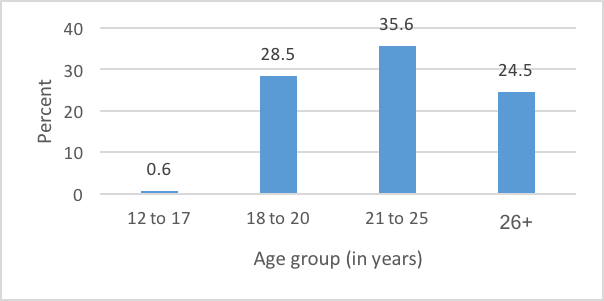

Tobacco: Almost 64 million individuals (24%) aged 12 and older reported recent (past month) use of tobacco products in the 2015 NSDUH survey (SAMHSA, 2016). The vast majority (52 million or 19%) used cigarettes. This is in comparison to cigars (4.7%), smokeless tobacco (3.4%) or pipe tobacco (0.8%). Figure 1 shows the age breakdown of those reporting past month tobacco use.

Figure 1. Past month tobacco use by age group (percent)

Caffeine: We have to turn to other sources to estimate the use of caffeinated beverages in the United States; the NSDUH survey does not ask about these substances. In a 2010-2011 population-based study, an estimated 85% of the U.S. population consumes at least one caffeinated beverage daily, with coffee being the primary contributor (Mitchell, Knight, Hockenberry, Teplansky, & Harman, 2014). Over the years, research has vacillated about the health benefits versus risks of drinking coffee. In studies that suggest benefits, the caffeine is not the factor contributing to protecting one’s health—it is other components in the coffee, many of which are still present in decaffeinated coffee, depending on the method used to decaffeinate the product (Gunter et al., 2017). And, the health risks accumulate with the flavorings we might add, such as high fat and calorie dairy and caloric sweeteners.

In addition to coffee, carbonated soft drinks, tea, and energy drinks/energy shots account for most of the caffeine consumed. Tea and carbonated soft drinks (like colas, Sunkist® orange, Dr. Pepper ® and Mountain Dew®) accounted for a great percentage of caffeine consumed by children and adolescents in the United States. Energy drinks accounted for less than 10% of the caffeine consumed by any age group, with the greatest use of energy drinks appearing in the 13-17 and 18-24 year old groups.

In addition to coffee, carbonated soft drinks, tea, and energy drinks/energy shots account for most of the caffeine consumed. Tea and carbonated soft drinks (like colas, Sunkist® orange, Dr. Pepper ® and Mountain Dew®) accounted for a great percentage of caffeine consumed by children and adolescents in the United States. Energy drinks accounted for less than 10% of the caffeine consumed by any age group, with the greatest use of energy drinks appearing in the 13-17 and 18-24 year old groups.

Now compare your predictions to what you read.

- The order they fall from most to least commonly used by individuals in the United States: caffeinated beverages (85%), tobacco (24%), amphetamines (1.67%), cocaine (0.7%), and methamphetamine (0.3%).

- For each substance except caffeinated beverages (that study did not analyze by gender), males more frequently reported using than females.

- For each substance, white non-Hispanic/non-Latino individuals most frequently reported using (except caffeinated beverages, that study did not analyze by race/ethnicity).

Substance Use Disorders Involving Stimulants

These stimulant use patterns, however, are only part of the picture. It is important to know how frequently people developed stimulant-related substance used disorders, too. Let’s look at the data from the NSDUH (SAMHSA, 2016) survey on this point.

- 29 million individuals met criteria for nicotine (cigarette) dependence; this is over half (55.7%) of persons who reported recent (past month) smoking of cigarettes.

- 896,000 individuals aged 12 and older met criteria for a substance use disorder involving cocaine; 702,000 were in the 26 and older age group.

- 872,000 individuals aged 12 and older met criteria for a substance use disorder involving methamphetamine.

- 426,000 individuals aged 12 and older met criteria for a substance use disorder involving simulant prescription misuse.

Age at Initiation

Finally, because we know that age at first use of substances plays a significant role in the probability of developing a substance use disorder, it is helpful to know the patterns in when young people start using. The 2015 NSDUH survey (SAMHSA, 2016) data indicate the following:

- 1.26 million persons initiated stimulant misuse during the past year; this represents 0.5% of the population

- 276,000 initiates of stimulant misuse were aged 12-17 years

- 600,000 initiates of stimulant misuse were aged 18-25 years

- 384,000 initiates of stimulant misuse were ages 26 or older

Perceived risk is considered to be one of the protective factors related to substance use initiation. However, among persons who began smoking cigarettes during the past year, 645,000 perceived there to be great risk in smoking one or more packs per day. Among persons who never initiated smoking, 779,000 held this perception. Perhaps those who initiated smoking did not believe there to be much risk in smoking less than a pack per day and did not anticipate eventually smoking in what they considered to be a high-risk pattern.

Among persons who initiated cocaine use during the past year, 228,000 perceived there to be great risk in using once a month and 478,000 perceived this level of risk associated with using once or twice a week. Individuals who never initiated cocaine use MUCH more commonly held the belief that it was used at great risk.