Module 9: Sedative/Hypnotics and CNS Depressants

Ch. 3: More About Sedative/Hypnotic and CNS Depressant Drugs

This chapter updates some of the information presented in earlier chapters and introduces a few more topics. In this chapter you will read about:

- more effects of these substances (including problems with driving under the influence)

- additional substances (non-benzodiazepine sleep medications, Quaaludes)

- polydrug use

- suicide risk

- key terms used in the field of substance use disorders and addiction.

More on Effects of These Substances

The topics of prescription drug abuse and the drugs known as sedative/hypnotics and CNS depressants overlap considerably. Whether prescribed or used (illegally) without a prescription, a drug still has the same actions on the brain, body, and behavior. The description below comes from a presentation to Congress by the director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), Dr. Nora Volkow, on September 22, 2010:

CNS depressants, typically prescribed for the treatment of anxiety, panic, sleep disorders, acute stress reactions, and muscle spasms, include drugs such as benzodiazepines (e.g, Valium, Xanax) and barbiturates (e.g., phenobarbitol)—which are sometimes prescribed for seizure disorders. Most CNS depressants act on the brain by affecting the neurotransmitter gamma-Aminobutyric acid (GABA), which works by decreasing brain activity. CNS depressants enhance GABA’s effects and thereby produce a drowsy or calming effect to help those suffering from anxiety or sleep disorders. These drugs are also particularly dangerous when mixed with other medications or alcohol; overdose can suppress respiration and lead to death. The newer non-benzodiazepine sleep medications, such as zolpidem (Ambien), eszopiclone (Lunesta), and zalepon (Sonata), have a different chemical structure, but act on some of the same brain receptors as benzodiazepines and so may share some of the risks—they are thought, however, to have fewer side effects and less dependence potential.

Driving Under the Influence of Medications

News reports in recent years have identified potential problems with non-benzodiazepine sleep medications. Sleeping medications like Ambien were reportedly involved in car crashes where Tiger Woods and Kerry Kennedy were reportedly driving under the influence of these legal substances. While it is clear to most of us that driving under the influence of alcohol is a bad idea (and illegal), too often people overlook the potential dangers associated with driving under the influence of other legal substances and prescription medications. The Automobile Association of America (AAA, 2014) reported that, while 66% of people consider driving under the influence of alcohol to be a very serious threat and 56% considered driving under the influence of illegal drugs to be so, only 28% consider driving under the influence of prescription drugs to be a very serious threat. They report that the crash risk increases by up to 41% for driving under the influence of certain antidepressants, and even over-the-counter cold and allergy medications can impair driving. The dangers also apply to operating any dangerous equipment or machinery, not only motor vehicles.

While their addictive potential may be less than for some of the other substances in this category, non-benzodiazepine sleep medications are not necessarily “safe” drugs across all types of risk. The increased risks are present even for people who take fewer than two pills monthly—they are still three times more likely to die than people who do not use these substances at all (Kripke, Langer, & Kline, 2012).

Quaaludes

One substance that we have not discussed so far is the sedative-hypnotic called methaqualone (known by the brand name Quaaludes, or by the street name “ludes” or “sopers”). Like the other drugs you are learning about in this module, overdose is possible with this substance, causing symptoms on a continuum of delirium, convulsions, kidney failure, coma, and death. This drug has been in the news recently because it is the substance that Bill Cosby admitted to administering to a number of women either without their knowledge or without their knowledge of the expected effects.

Polydrug Use

What is particularly important to know, especially given the “club” drug culture surrounding use, is that it takes only ¼ as much of certain drugs when combined with alcohol to induce coma. A large percentage of drug-related deaths and fatal overdose situations involved the combination of opioids or heroin with benzodiazepines. This point is important across our course: polydrug use is potentially very risky. Combining alcohol with the use of any of the substances we are studying is a form of polydrug use.

Risk of Suicide

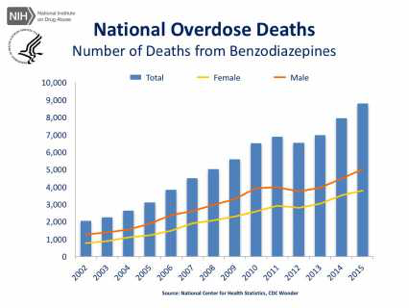

Non-medical use (prescription abuse) of sedative-hypnotic medications is a significant risk factor for suicide, as is the abuse of alcohol (Dodds, 2017): sleeping pills and other sedative drugs is associated with a three-fold higher risk of suicide attempt. According to a recent review of literature (Dodds, 2017), the increased risk of attempted or completed suicide seems to be present with prescribed use, as well. It is not clear whether different specific medications have different associated risk, only that the class of substances (particularly benzodiazepines) has this increased risk. The picture is further complicated by the difficulty in many instances of separating accidental overdose deaths from suicide attempts resulting in death. We do know that the rate of death from benzodiazepine overdose has climbed in recent years (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Trend in U.S. overdose deaths from benzodiazepines (NIDA, 2017)