Module 11: Opioids

Ch. 1: The Opioid Epidemic

In recent months, news about an opioid epidemic has shaped a large portion of the national discourse and policy at the local, state, and federal levels. Before delving into details about these substances, we will first look at the context presented by the “epidemic narrative.” The first reading for Module 11 is a fact sheet prepared by the American Society of Addiction Medicine, Opioid addiction: 2016 facts & figures. The second reading is from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA, 2017) and addresses the nation’s opioid crisis.

In this first chapter you will read about:

- the class of opioid drugs;

- epidemiology and economic burden related to opioid addiction;

- the relationship between opioid and heroin misuse;

- the role of fentanyl and carfentanil in opioid overdose rates;

- a brief summary of how this problem came to be1;

- possible strategies for addressing the problem; and,

- key terms related to opioid misuse and addiction.

As you are doing the readings for Chapter 1, keep several points in mind. First, the purpose of these drugs, initially, was pain control—they were originally prescribed because of their analgesic properties. They reduced or eliminated many types of pain from many parts of the body. They work on pain through the endorphin systems that we studied earlier in our coursework. Because of their

side effects (and addictive potential) they are usually reserved for treating severe pain or maybe moderate pain of a short duration. Many physicians were trained to believe that these pain medications were not addictive for patients truly experiencing pain. This mistaken belief, combined with being trained to believe that failing to adequately manage pain was unethical, led to much over-prescribing of these medications. This was only part of the opioid problem spiraling out of control.

Second, while a great deal of attention related to the opioid epidemic is directed toward death statistics, it is also important to remember that death is not the only worrisome outcome. According to Ohio’s Franklin County Opiate Action Plan (2017) and other sources:

- The number of deaths due to accidental drug overdose increased by 71% between 2012 and 2016—only a 4 year span;

- This increase is largely driven by deaths due to fentanyl, the highest rate occurring among 25-34 year olds, 70.5% of whom were men;

- At least 3 out of 4 persons who use heroin report first misusing prescription opiates;

- The number of persons infected with Hepatitis C increased by 68% between 2012 and 2016 (from 950 to 1600)

- Neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) rates climbed precipitously [from 20 babies per 10,000 live births to 155 babies per 10,000 live births between 2006 and 2015, according to state records described in the news http://wcbe.org/post/rate-ohio-babies-born-addicted-drugs-increasing ];

- Children’s services report that 70% of children under the age of one year who are in custody have opiate-involved parents and 28% of all children taken into custody had parents using opiates at the time of removal from the home;

- In 2011, first responders administered an average of 6.55 doses of naloxone per day; in 2016 this rate was up to 10.3 doses per day—largely accounted for by the ever-stronger strains of opiates being used needing more naloxone per person to combat overdose (the average number of incidents requiring naloxone administration increased from 5.2 per day in 2011 to 6.5 per day in 2016);

- Law enforcement seizure of fentanyl events increased from 110 during 2013 to 3,882 in 2015;

- For every overdose death, there were 32 emergency department visits;

- Efforts to obtain heroin and other opioid substances often involves criminal activity (over and above the distribution being illegal), especially property crimes and robbery (stealing from a person);

- Violent crime and weapons are often involved in the illegal distribution of these substances.

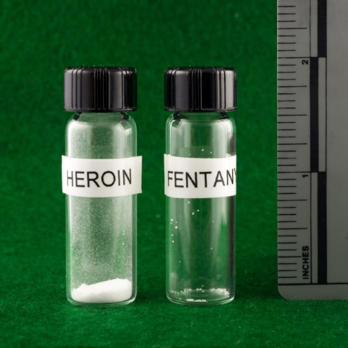

Third, the opioid picture is seriously compounded by the emergence of fentanyl and carfentanil (or carfentanyl) onto the scene. Accidental overdose involving these more powerful synthetic opioid substances is all too easy. Fentanyl has 50-100 times the potency of street heroin. Carfentanil has 100 times the potency of fentanyl. Carfentanil was originally formulated to sedate elephants, not for human use. These two drugs are showing up as additives to a variety of “street” drugs—heroin, reconstructed opioid pills, cocaine, and marijuana.

Recently, first responders and drug-detection dogs have experienced overdose events as a result of accidentally coming into contact with even very small quantities of these substances. The photo in Figure 1 comes from the New Hampshire State Police Forensic Lab (see https://www.statnews.com/2016/09/29/fentanyl-heroin-photo-fatal-doses/ ). The DEA has issued a nationwide law enforcement alert that breathing in or touching even small specks of fentanyl can cause a fatal overdose—amounts similar to a few grains of table salt (https://ndews.umd.edu/sites/ndews.umd.edu/files/DEA%20Fentanyl.pdf ). Now, imagine the small amount of carfentanil exposure that could be fatal. Finally, think about the implications of these substances being loose in the community—present on discarded drug paraphernalia or contaminating household or auto furnishings. This is similar to an issue we explored when we looked at the community impact of illegal methamphetamine production—these substances represent environmental hazards to others who may not be aware of their presence.

Figure 1. Comparing lethal doses of heroin and fentanyl

“On the left, a lethal dose of heroin; on the right, a lethal dose of fentanyl.”

1 Additionally, you may be interested in reading Sam Quinones’ book, Dreamland: The True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic, if you are interested in an analysis of how the nation got from heroin being a back alley drug during the 1970s to “now it’s your neighbor’s child,” and the role of pharmaceutical companies in the developing opioid tidal wave (2015).

Click here for a link to our Carmen course where you can locate the assigned pdf file(s) for this chapter. You will need to be logged into our Carmen course, select Module 1, and proceed to the Coursework area. Under the Readings heading you will find a box with links to the readings for relevant coursebook chapters. Don’t forget to return here in your coursebook to complete the remaining chapters and interactive activities.