Skill Group: Biosafety and Biosecurity

Types of PPE and Indications for Use Based on Risk Assessment

Before You Start …

You have previously learned that there are 5 routes by which pathogens can be transmitted, pathogens can remain in the environment for varying lengths of time (sometimes for months or longer) and pathogens vary in their infectivity, virulence, pathogenicity and zoonotic potential. We will build upon this information to help us determine the type(s) of risk present, who may be at risk of infection, and the best PPE items to choose for a given scenario.

Introduction

Identifying and characterizing risks, or hazards, that are present in a particular setting will reduce the likelihood that person and patient injury or illness will occur. As veterinarians, we have a legal responsibility to protect ourselves, our staff, our patients, and our clients from hazards that may be present in the clinical setting. This can be done through proper Risk Assessment. For the purposes of this module, we will focus specifically on biological hazard risk and using the Risk Assessment process to guide our personal protective equipment (PPE) selection.

Choosing the appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) for a given situation is critical. If we ‘under dress’ (choose a lower level of PPE items than is indicated), our efforts may not be adequate to prevent pathogen contamination and transmission. If we ‘over dress’, we may be wasting resources (time, expenses), which can also impact the care that we are able to provide to the patient. Some novices may feel it is difficult to determine the best PPE items for a given scenario, however with an understanding of how to perform a risk assessment, the types of PPE items generally used, rationale for each of these items, and building off our prior learning lesson, this decision can be correctly made by all of us.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- Describe commonly encountered PPE in clinical veterinary practice, what it protects, and when it is indicated.

Risk Assessment is a systematic process that is employed in many different facets including healthcare setting infection control, food safety, environmental health, emergency preparedness/disaster planning, and pharmaceutical safety. Its broad application can result in some mild variations in implementation, however, the overall goal remains the same: eliminate hazards (risks) when possible and reduce the level of risk associated with hazards through various controls measures when not. To achieve this goal, consistency is key.

For teaching and examination purposes, the Risk Assessment steps taught in this training are what is expected for assessments related to this learning unit. Outside of a student assessment here at The Ohio State University, you should follow the specific protocols for each service and hospital in which you work.

The process of Risk Assessment consists of 3 steps:

- Risk Assessment

- Risk Management

- Risk Communication

Risk Assessment is the process of identifying and characterizing risks. This is accomplished by:

- Creating a list of potential hazards (biological, chemical, physical, etc.)

- Characterizing the identified hazards- for this lab we are specifically focusing on biological hazards. Characterization of these hazards is influenced by whether the etiologic agent is known or unknown.

- If known, consider the following when assessing risk:

- Likelihood of exposure based on known transmission route(s)

- Hazard severity based on infectivity, pathogenicity, virulence

- If unknown, consider the following when assessing risk:

- Patient age, vaccination status, diet, and husbandry

- Patient travel history

- Patient contact with other animals (domestic or wild)

- Clinical signs as these may indicate potential routes of transmission

- If known, consider the following when assessing risk:

- Identifying who is at risk and why – for biological hazards this could include:

-

- Other patients or pets in the household

- Clients and their family

- Clinic staff – veterinarians, technicians, assistants, kennel workers, receptionists, groomers, volunteers

Risk Management is a decision-making process that involves using information obtained from risk assessment to identify and implement appropriate control measures to eliminate or reduce risk. It is important to consider the Hierarchy of Controls discussed in Lesson 1 during this process to identify the most effective measure that can realistically be put in place to achieve this goal. In this lab, we will assume that PPE use is the only available control measure.

Finally, Risk Communication is informing your target audience (i.e. the population at risk) of the hazards identified and how they can act to reduce their risk. Veterinarians must educate their staff and clients about potential zoonotic risks and how to prevent infection. In the clinical setting, veterinarians are legally required by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) to provide necessary PPE and ensure its proper use.

PPE training should include the following information:

- When it is necessary

- What kind/level of PPE is necessary

- How to properly don, adjust, wear, and doff PPE

- The limitations of the equipment

- Proper care, maintenance, durability, and disposal of PPE

The next section of this lesson, will explore these concepts further.

Types of PPE

There are 5 main types of PPE worn in veterinary clinical scenarios. These are:

- Gloves;

- Body/clothing protection, such as gown, coveralls, and laboratory coat;

- Foot protection, such as foot covers (booties) and dedicated footwear;

- Face protection, such as mask (surgical), goggles, and face shield;

- Respiratory protection, such as N-95 respirator mask.

An important note regarding all PPE items – PPE items should always be considered single-use and used by only one person (after which it is disposed or cleaned and disinfected). This rule holds even for interactions with the same patient. It is generally impossible to don contaminated PPE items without contaminating the “clean” surfaces of the item, the environment or yourself.

Let’s discuss each category, the options available, when they should be used, and common errors when using them. The linked figure can be used to remind you of the various types of PPE and when they are indicated.

Gloves

Non-sterile disposable gloves protect our hands from contamination. These should be impermeable, single-use latex, nitrile, or vinyl gloves of appropriate size for the individual. They should be worn when:

- Having contact with an animal with a suspected infectious disease (or its environment – cage, etc);

- Having contact with a patient’s blood, body fluids, secretions, excretions, non-intact skin, mucous membranes;

- Cleaning animal contact/housing areas (e.g., cages, stalls).

Note: Sterile gloves should be used when the primary risk is transmission of pathogens to (rather than from) a particular body site or item (eg, surgery, examination of “clean” wounds).

Hand hygiene (washing with soap and water or using alcohol-based hand sanitizer) should occur immediately before and after removing gloves. This is to ensure we do not contaminate the outside of the gloves before donning and remove any contamination due to improper technique or inherent defects in the gloves after doffing. Surprisingly, many veterinarians do not correctly perform hand hygiene. We will tackle the specifics of hand hygiene (e.g., how best to do it) in a separate section.

When wearing gloves, do NOT touch surfaces to be touched by people with non-gloved hands (e.g., computer keyboard). If you do, you are likely contaminating these surfaces and undoing many of the benefits of wearing gloves.

Body/clothing protection

Gown, coveralls or laboratory coat protect our clothing and skin from contamination. A laboratory coat, or dedicated clothing such as scrubs, should be worn whenever having contact with animals or their environment. Disposable gowns or coveralls (or reusable items including laboratory coats that are immediately laundered after each patient use), should be worn when there is risk for contact with areas of your body in addition to your hands when:

- Having contact with a patient’s blood, body fluids, secretions, excretions, or non-intact skin;

- Having contact with an animal with a suspected infectious disease (or its environment – cage, etc).

Items used for the above scenarios should be single-use disposable gowns or reusable cloth gowns or laboratory coats that are laundered after each applicable patient contact or procedure.

These items come in a variety of types (e.g., re-usable laboratory coat, single use zipper-up coveralls with hood) and materials (e.g., cloth, disposable easily permeable to liquids, disposable fluid-resistant). The decision on what to use will depend on the clinical situation, including the pathogen(s) of concern (e.g., route(s) of transmission, infectivity, pathogenicity, virulence, environmental stability, zoonotic potential, level of risk to patients and staff) as well as cost and ease of donning and doffing.

Foot protection

Foot covers (booties) or dedicated footwear protect our feet and footwear from contamination. These items are warranted whenever, there is risk for:

- Having contact between your feet and a patient’s blood, body fluids, secretions, and excretions;

- Having contact between your feet and an animal with a suspected infectious disease (or its environment – cage, etc).

Items used for the above should be single-use disposable cloth or plastic boots that fit over regular footwear or reusable slip-on footwear that is easily cleaned and disinfected (eg, rubber boots).

Common examples of when foot covers or dedicated footwear is indicated include entering the run of a dog diagnosed with parvovirus or the stall of a horse with salmonellosis, or managing large open wounds in a patient if the floor could become contaminated with discharge or lavage fluid. In contrast, these items are not indicated when retrieving from a cage and working on a cat with a multi-drug resistant bacterial skin infection as it is very unlikely our shoes will become contaminated.

Note: Disposable plastic shoe covers can create a slipping hazard if they do not have treads.

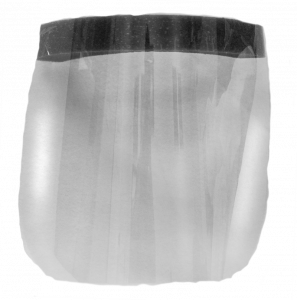

Face protection

Face protection, such as masks (surgical), plastic goggles (that wrap around the sides of the face or include side-protectors), and full-face shields, are used to prevent exposure of the mucous membranes (e.g., eyes, nose, mouth) to pathogens. These items may be worn as a single piece (face shield) or multiple pieces (googles and surgical mask) to accomplish this task. These items are warranted whenever, there is a risk for splashes or sprays onto a person’s mucous members, such as during the following situations:

- Dental procedures

- Wound lavage

- Working on an abscess

- Obstetrics

- Necropsy

Items used for the above should be single-use disposable (surgical mask) or reusable after cleaned and disinfected (face shield, goggles).

Respiratory protection

Respiratory protection, such as N-95 masks, filter particulate aerosols. As such, these items protect against contact with mucous membranes as well as against inhalation of pathogens. These items are warranted whenever there is a risk of a zoonotic pathogen that is transmitted by the airborne route (very small particles that remain suspended in the air for prolonged periods). Currently, such pathogens are very uncommon in routine veterinary practice in the United States. Examples include pneumonic tularemia, avian influenza, and bovine tuberculosis.

To work properly, respirators need to be fit-tested. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) (29 CFR 1910.134) requires an annual respirator fit test to confirm the fit of any respirator that it forms a tight seal on the wearer’s face before it is used in the workplace. This ensures that users are receiving the expected level of protection by minimizing any contaminant leakage into the facepiece (learn more about fit testing).

Surgical masks are NOT respirators. They are designed to protect patients (not the user) from large droplets. Additionally, they can provide the user some protection from splashes as stated above. The material used in surgical masks and large gaps between the face and mask do not provide adequate filtration to be used for airborne zoonotic pathogens.

Wrapping Up

In this lesson, we discussed the commonly encountered PPE in clinical veterinary practice, what it protects, and when it is indicated. Now we are ready to build off this knowledge to discuss how to appropriately don PPE to ensure it provides the protection we intend.

Before Moving On …

We have prepared a few scenarios related to Risk Assessment and PPE-use for you to check your knowledge!”