Chapter 11: CG Production Companies

11.3 Pixar

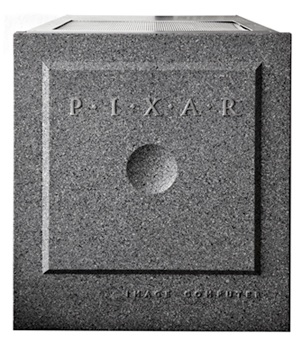

The origins of Pixar were at the heart of the graphics lab at NYIT. This group was largely moved to ILM after Lucas recruited Ed Catmull to develop a computer graphics group there in 1979. As was discussed in the previous section of this chapter, many innovative hardware and software technologies were developed at ILM, including what was called the Pixar Image Computer.

On February 3, 1986 Steve Jobs paid $5M to ILM to purchase the rights to the technology, and invested another $5M to capitalize a new company that could utilize the technology in production. The new company was called Pixar, Inc. ILM retained the rights to use the technology in house, and continued animation work there. The Pixar Image Computer, which was intended for the high-end visualization markets, such as medicine, was eventually sold to Vicom Systems for $2M ( a video showcasing the Pixar Image Computer can be viewed at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ckE5U9FsgsE.) At that time, 18 Pixar employees were also transferred out.

According to Alvy Ray Smith in a series of documents on his web site, George Lucas decided to refocus his efforts, so Smith and Ed Catmull contacted several venture capitalist groups, and several individuals and/or companies (including a partnership of General Motors’ EDS computer services company, owned by H. Ross Perot, and a unit of Dutch electronics conglomerate Philips NV) to try to find funding to finance the spinoff, before Jobs came forward with his investment.

Ed Catmull became head of the new company and Alvy Ray Smith became Vice President. Most employees of the division at ILM (40 in all, including Malcolm Blanchard, Loren Carpenter, Rob Cook, David DiFrancesco, Ralph Guggenheim, Graig Good, John Lasseter, Eban Ostby, Tom Porter, Bill Reeves, and others) left for Pixar.

The early years of the company were tough, from a financial perspective. The sales of the Pixar Image Computer were slower than anticipated, resulting in the Vicom sale. The cost of computing frames of animation (particularly for film) was still very high, so the company did animation for advertising, including fairly well-known CGI ads for Listerine, Tropicana and Lifesavers (several won Clio Awards.)

Movie 11.4 Listerine – 1994

This commercial production effort by Lasseter’s group kept a small revenue stream coming in to the company, but additional funding was needed. Steve Jobs continued to provide these needed funds by converting the equity of the employees who originally owned a percentage of the company, ultimately putting in $50M and becoming the dominant stockholder. [1]

In 1990 Pixar moved their headquarters to Richmond, just across the bridge from San Rafael in Marin County. In 2002 they again moved, this time to a large campus on 15 acres in Emeryville. A description of the Emeryville HQ of Pixar from the architect’s web site can be found here.

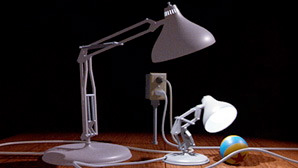

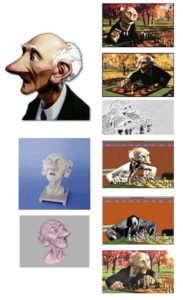

Image production during these formative years also included work on animated short film productions, most notably Luxo Jr. (1986), Red’s Dream (1987), Tin Toy (1988), KnickKnack (1989) and Geri’s Game (1997). Pixar won Oscars for Tin Toy in 1988 (Luxo Jr. was nominated in 1986) and Geri’s Game in 1998.

Software created by Pixar in the first few years (or expanded from that developed at the ILM division) included the REYES (Renders Everything You Ever Saw) renderer, CAPS (developed for Disney), Marionette, an animation software system that allowed animators to model and animate characters and add lighting effects, and Ringmaster, which was production management software that scheduled, coordinated, and tracked a computer animation project. The film recording technology mastered by David DeFrancisco was incorporated into a new laser film recorder called PixarVision.

The applications development group also worked to convert the REYES technology to the RenderMan product, which was commercialized in 1989. Saty Raghavachary, a graduate of Ohio State’s graphics program and a software developer at Dreamworks, summed up the development clearly in notes for a course on RenderMan at the Siggraph 2006 conference:

The researchers had the explicit goal of being able to create complex, high quality photorealistic images, which were by definition virtually indistinguishable from filmed live action images. They began to create a renderer to help them achieve this audacious goal. The renderer had an innovative architecture designed from scratch, incorporating technical knowledge gained from past research both at Utah and NYIT. Loren Carpenter implemented core pieces of the rendering system, and Rob Cook wrote the shading subsystem. Pat Hanrahan served as the lead architect for the entire project.

The architecture embedded in RenderMan was presented in a paper by Cook, Carpenter, and Ed Catmull at Siggraph 87. [2], and the shader was documented in a 1990 paper by Hanrahan and Jim Lawson. [3]. The system was used in the creation of the Academy Award winning Tin Toy in 1988. A sequence of images, which has become quite famous, was created to demonstrate the capabilities of the software, and the stages of the rendering pipeline. Called the “Shutterbug” series, it has been used countless times to teach students the concepts of rendering.

RenderMan, or Photorealistic RenderMan (PRMan) as it is properly known, is actually a formal specification, or an interface description to provide a standard for modeling and animation programs to specify scene descriptions to rendering software. In February, 1989, nine months after Pixar promoted the scene description language, InfoWorld magazine announced the commercialization of the RenderMan imaging technology. Autodesk was the first licensee, wanting to include it in their AutoShade product. [4]

The group received Academy Technical Awards in 1992 for CAPS,1993 for RenderMan, 1995 for digital scanning technology, 1997 for Marionette and digital painting, and 1999 for laser film recording technology.

Steve Jobs discontinued the applications development effort in 1991, ostensibly because of a fear of competition with the NeXT product development efforts. As a result, nearly 30 people were laid off, including Alvy Ray Smith, who with two others then founded Altamira, with support from Autodesk. This reduced the total number of employees to about its original number of 40. At that point, the developers who were working on CAPS for Disney and Photorealistic RenderMan, and Lasseter’s commercial animation department were all the employees left at Pixar.

At that point, Disney executives and the leadership team at Pixar signed a $26 million deal with Disney to produce three computer-animated feature films, the first of which was Toy Story. In an article in Fortune Magazine Brent Schlender reported

In 1991, Lasseter felt the Pixar technology was robust enough to make an hour-long computer-animated TV special. He pitched the idea to Disney, hoping the big studio would help fund the project. Jeffrey Katzenberg, who was running Eisner’s film business, was already enamored of Lasseter’s style. (Now a principal of DreamWorks, Katzenberg contends that the director is Pixar’s biggest asset.) Katzenberg and Eisner came back with an unexpected counteroffer: How about making a full-scale movie that Disney would pay for and distribute?

Not surprisingly, Jobs, who’d been absorbed by the trials and tribulations at Next, suddenly started paying more attention to his other company. He got involved in the negotiations with Disney, and hired one of Hollywood’s most respected entertainment lawyers to help hammer out a deal. The result was a contract for Pixar to make three feature films. Disney would pick up most of the production and promotion costs, as long as it had complete control over marketing and licensing the films and their characters. Pixar would create the screenplays and the visual style for each picture and receive a percentage of the box-office gross revenues and video sales.

Jobs has to be given a lot of credit for sticking with the company. At several points, he considered selling it (it is reported that one potential buyer was Microsoft), but he ultimately realized, as Toy Story was wrapping up and Disney confirmed a Christmas release, that the company had tremendous potential and backed away from the desire to sell it.

In 1995 Pixar went public with an offering of 6,900,000 shares of stock. Shares opened at $47, more than double their offering price of $22, and at the closing price of $39 per share, the company had a market value of about $1.5 billion.

After successes with Toy Story, the Pixar interactive group developed two CD-ROMs, but were refocused in 1997 in order to concentrate the corporate effort on making films. In 1997 the two organizations (Pixar and Disney) announced a five picture agreement, including a sequel to Toy Story. Pixar produced the 1998 animated feature A Bug’s Life, which set box office records, Toy Story 2, Monsters, Inc. and Finding Nemo.

- Scene from Toy Story

- Scene from A Bug’s Life

Pixar and Disney went through a period of several public disagreements, particularly around the production and quality of Toy Story 2, as well as Disney’s ownership of story and sequel rights, and Jobs’ not so quiet disdain for Michael Eisner. They attempted to come to an agreement, but both companies held firm on their demands. Pixar’s contention was reported in the media:

Pixar had complained that the terms of the distribution deal were tilted too heavily in Disney’s favor. Under the deal, Pixar was responsible for content, while Disney handled distribution and marketing. In exchange, Pixar has split profits with Disney and pays the studio a distribution fee of between 10 percent to 15 percent of revenue. Based on its blockbuster success, Pixar has argued that it should keep the profit itself and cut the fees its studio partner charges.

Talks broke down in 2004, and Wired Magazine reported that Pixar Says Goodbye to Disney. Following that, Jobs reportedly entered into distribution discussions with Time Warner, Sony and Viacom, though no agreement was settled on. Talks with Disney resumed after Eisner left Disney in 2005.

Disney announced in early 2006 that it had agreed to buy Pixar for approximately $7.4 billion in an all-stock deal. Jobs gained a seat on the Disney board of directors and gave him 7% ownership. Lasseter, became Chief Creative Officer of both Pixar and the Walt Disney Animation Studios, as well as the Principal Creative Adviser at Walt Disney Imagineering, which designs and builds the company’s theme parks. Catmull retained his position as President of Pixar, while also becoming President of Walt Disney Animation Studios.

Movie 11.5 Luxo, Jr.

The collection of short films, trailers and outtakes produced at Pixar can be seen at their corporate website at

http://www.pixar.com/short_films/Theatrical-Shorts

Home Designing.com has a photo tour of the Pixar headquarters at

http://www.home-designing.com/2011/06/pixars-office-interiors-2

An interview with the Pixar executives can be viewed at

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YjSExqtiIyg

Gallery 11.1 Frames from Pixar Shorts

- Luxo, Jr.

- Red’s Dream

- Tin Toy

- Knick-Knack

- Geri’s Game

- Alvy Ray Smith documented the history of Pixar in an article called Pixar History Revisited - A Corrective, in which he takes on the myths that Jobs started, or bought Pixar. http://www.alvyray.com/Pixar/PixarHistoryRevisited.htm ↵

- Cook, Rob, Carpenter, Loren, and Catmull, Ed. The Reyes Image Rendering Architecture, ACM SIGGRAPH Computer Graphics, Volume 21 Issue 4, July 1987, Pages 95-102 ↵

- Hanrahan, Pat, and Lawson, Jim. A Language for Shading and Lighting Calculations, ACM SIGGRAPH Computer Graphics, Volume 24, Issue 4, September 1990, Pages 289-298 ↵

- In their July, 2013 issue, fxguide magazine published an interview with Ed Catmull and Loren Carpenter on the 25th anniversary of the release of the RenderMan 3.0 interface. It can be read online at https://www.fxguide.com/featured/pixars-renderman-turns-25/ A podcast of the interview with Ed Catmull accompanies the article at https://www.fxguide.com/fxpodcasts/fxpodcast-257-pixars-ed-catmull/ ↵