Chapter 3: The computer graphics industry evolves

3.1 Work continues at MIT

As mentioned in the previous chapter, activities at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology helped shape the early computer and computer graphics industries. Development at MIT took place in several different laboratories, including the Lincoln Labs, Electronics System Laboratory, the Center for Advanced Visual Studies, the Architecture Machine Group and the Media Lab. As mentioned in Chapter 1, Jay Forrester of the Servomechanisms Lab was chosen by Gordon Brown to develop the Whirlwind computer in the mid-40s. The Whirlwind and Forrester were moved to the Digital Computer Lab and started focusing on using the computer for graphics displays, for air traffic control and gunfire control, and became part of the government’s SAGE (Semi-Automatic Ground Environment) program.

Ivan Sutherland and Sketchpad

Ivan Sutherland, acknowledged by many to be the “grandfather” of interactive computer graphics and graphical user interfaces, worked on his PhD in Electrical Engineering in the Lincoln Labs on their TX-2 computer. Sutherland learned to program in high school using a small relay computer called SIMON[1].

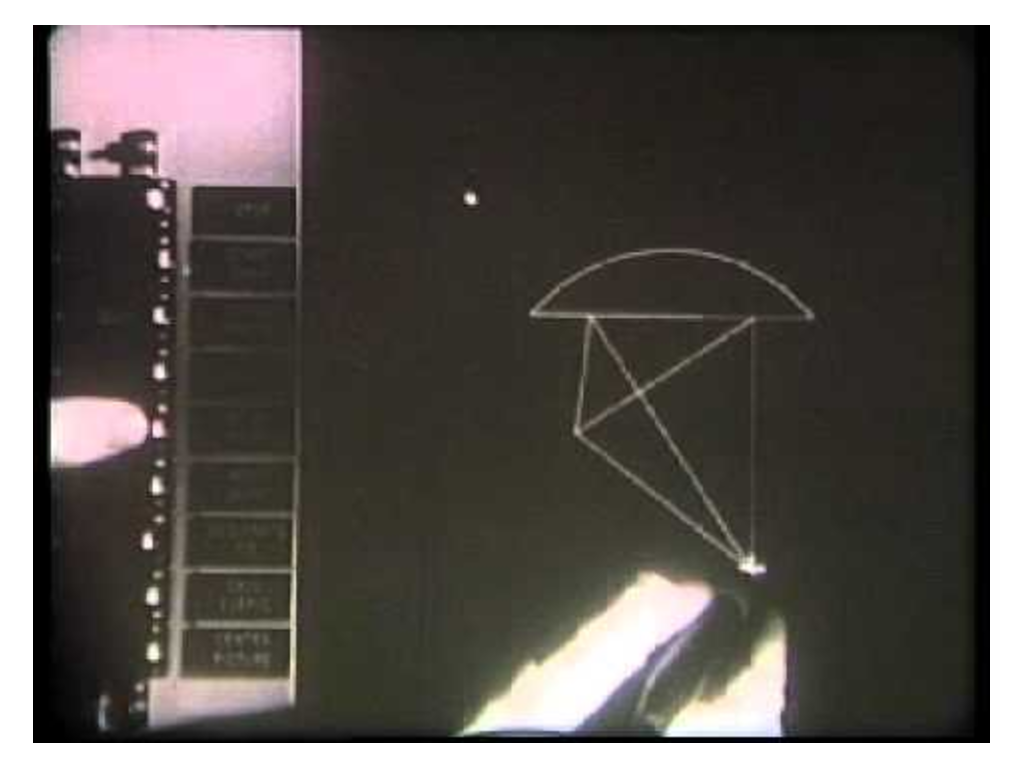

This was the beginning of a distinguished career in computers, graphics, and integrated circuit design. He earned his B.S. in Electrical Engineering at Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University) on a full scholarship. He received an M.S. from Cal Tech, and then enrolled at MIT to work on his Ph.D. His dissertation centered around an interactive computer drawing program that he called Sketchpad, which was published in 1963. His contributions moved graphics from a military laboratory tool to the world of engineering and design. Sutherland made a movie of the interactive use of Sketchpad, which became somewhat of a cult film. It is widely acknowledged that every major computer graphics research lab in the country had a copy of the film, and researchers and students still refer to it over and over, as it influenced their developmental work so significantly.

Excerpted from a 1987 distinguished lecture series by computer interface pioneer Alan Kay, titled “Doing with Images Makes Symbols: Communicating with Computers”

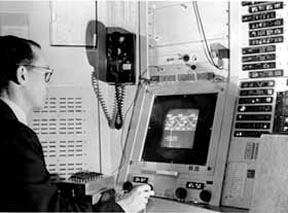

Sutherland’s software, described in a 1963 paper, Sketchpad: A Man-machine Graphical Communications System, used the light pen to create engineering drawings directly on the CRT. Highly precise drawings could be created, manipulated, duplicated, and stored. The software provided a scale of 2000:1, offering large areas of drawing space. Sketchpad pioneered the concepts of graphical computing, including memory structures to store objects, rubber-banding of lines, the ability to zoom in and out on the display, and the ability to make perfect lines, corners, and joints. This was the first GUI (Graphical User Interface) long before the term was coined.

The following text is from a citation for Dr. Sutherland when he won the Franklin Institute Certificate of Merit (1996):

At a time when cathode ray tube monitors were themselves a novelty, Dr. Ivan Sutherland’s 1963 software-hardware combination, Sketchpad, enabled users to draw points, line segments and circular arcs on a cathode ray tube with a light pen. In addition Sketchpad users could assign constraints to whatever they drew and specify relationships among the segments and arcs. The diameter of arcs could be specified, lines could be drawn horizontally or vertically, and figures could be built up from combinations of elements and shapes. Figures could be copied, moved, rotated, or resized and their constraints were preserved. Sketchpad also included the first window-drawing program and clipping algorithm which made possible the capability of zooming in on objects while preventing the display of parts of the object whose coordinates fall outside the window.

The development of the Graphical User Interface, which is ubiquitous today, has revolutionized the world of computing, bringing to large numbers of discretionary uses the power and utility of the desk top computer. Several of the ideas first demonstrated in Sketchpad are now part of the computing environments used by millions in scientific research, in business applications, and for recreation. These ideas include:

- the concept of the internal hierarchic structure of a computer-represented picture and

- the definition of that picture in terms of sub-pictures;

- the concept of a master picture and of picture instances which are transformed versions of the master;

- the concept of the constraint as a method of specifying details of the geometry of the picture;

- the ability to display and manipulate iconic representations of constraints;

- the ability to copy as well as instance both pictures and constraints;

- some elegant techniques for picture construction using a light pen;

- the separation of the coordinate system in which a picture is defined from that on which it is displayed; and

- recursive operations such as “move” and “delete” applied to hierarchically defined pictures.

The implications of some of these innovations (e.g., constraints) are still being explored by Computer Science researchers today.

Sutherland, Ivan, SKETCHPAD: A Man-Machine Graphical Communication System, PhD dissertation, MIT, 1963. Reproduced as Technical Report Number 574, University of Cambridge Computer Laboratory, UCAM-CL-TR-574, ISSN 1476-2986,

http://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/

Sutherland, Ivan, SKETCHPAD: A Man-Machine Graphical Communication System, Proceedings of the AFIPS Spring Joint Computer Conference, Detroit, Michigan, May 21-23, 1963, pp. 329-346.

http://www.guidebookgallery.org/articles/

Toward a Machine with Interactive Skills, from Understanding Computers: Computer Images, Time-Life Books, 1986

More on Ivan Sutherland can be found in the chapters and sections related to the University of Utah and Evans & Sutherland Computer Company (Chapters 4 and 13, respectively.)

Movie 3.2 Sketchpad

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=57wj8diYpgY

A copy of the first 6 1/2 minutes of the original Sketchpad demo, originally recorded on 16mm film

Center for Advanced Visual Studies

The Center for Advanced Visual Studies was established in 1967. Its founder, the artist and MIT professor Gyorgy Kepes, conceived of the Center as a fellowship program for artists.

The Center’s initial mission was twofold:

- to facilitate “cooperative projects aimed at the creation of monumental scale environmental forms” and

- to support participating fellows in the development of “individual creative pursuits.”

To achieve these goals, fellows worked collaboratively with each other and with the wider MIT community. Other fellows at CAVS extended this idea of artists working on projects with the assistance of engineers and scientists.

Kepes, who had taught at the New Bauhaus in Chicago prior to joining the faculty of MIT’s School of Architecture and Planning in 1946, strongly believed in the social role of the artist. With the founding of the Center he sought to bring about the “absorption of the new technology as an artistic medium; the interaction of artists, scientists, engineers, and industry; the raising of the scale of work to the scale of the urban setting; media geared to all sensory modalities; incorporation of natural processes, such as cloud play, water flow, and the cyclical variations of light and weather; [and] acceptance of the participation of ‘spectators’ in such a way that art becomes a confluence.”

According to the MIT CAVS website,

The CAVS was established by Professor Kepes, who emphasized the responsibilities of artists in building bridges between individuals and their environment, between individuals in groups, and between each of us and our inner lives.

MIT Media Laboratory

The Media Laboratory was formed in 1980 by Nicholas Negroponte and Jerome Wiesner, growing out of the Architecture Machine Group, and building on the seminal work of faculty members such as Marvin Minsky in cognition, Seymour Papert in learning, Barry Vercoe in music, Muriel Cooper in graphic design, Andrew Lippman in video, and Stephen Benton in holography. The Media Lab conducted advanced research into a broad range of information technologies including digital television, holographic imaging, computer music, computer vision, electronic publishing, artificial intelligence, human/machine interface design, and education-related technologies. Its charter was to invent and creatively exploit new media for human well-being and individual satisfaction without regard to present-day constraints. They employed supercomputers and extraordinary input/output devices “to experiment today with notions that will be commonplace tomorrow.” The not-so-hidden agenda was to drive technological inventions and break engineering deadlocks with new perspectives and demanding applications.

http://www.media.mit.edu/about/index.html

- A 1950 fact sheet from Columbia University called SIMON "a very simple model, mechanical brain -- the smallest complete mechanical brain in existence." This fact sheet can be found at http://www.blinkenlights.com/classiccmp/berkeley/simonfaq.html ↵