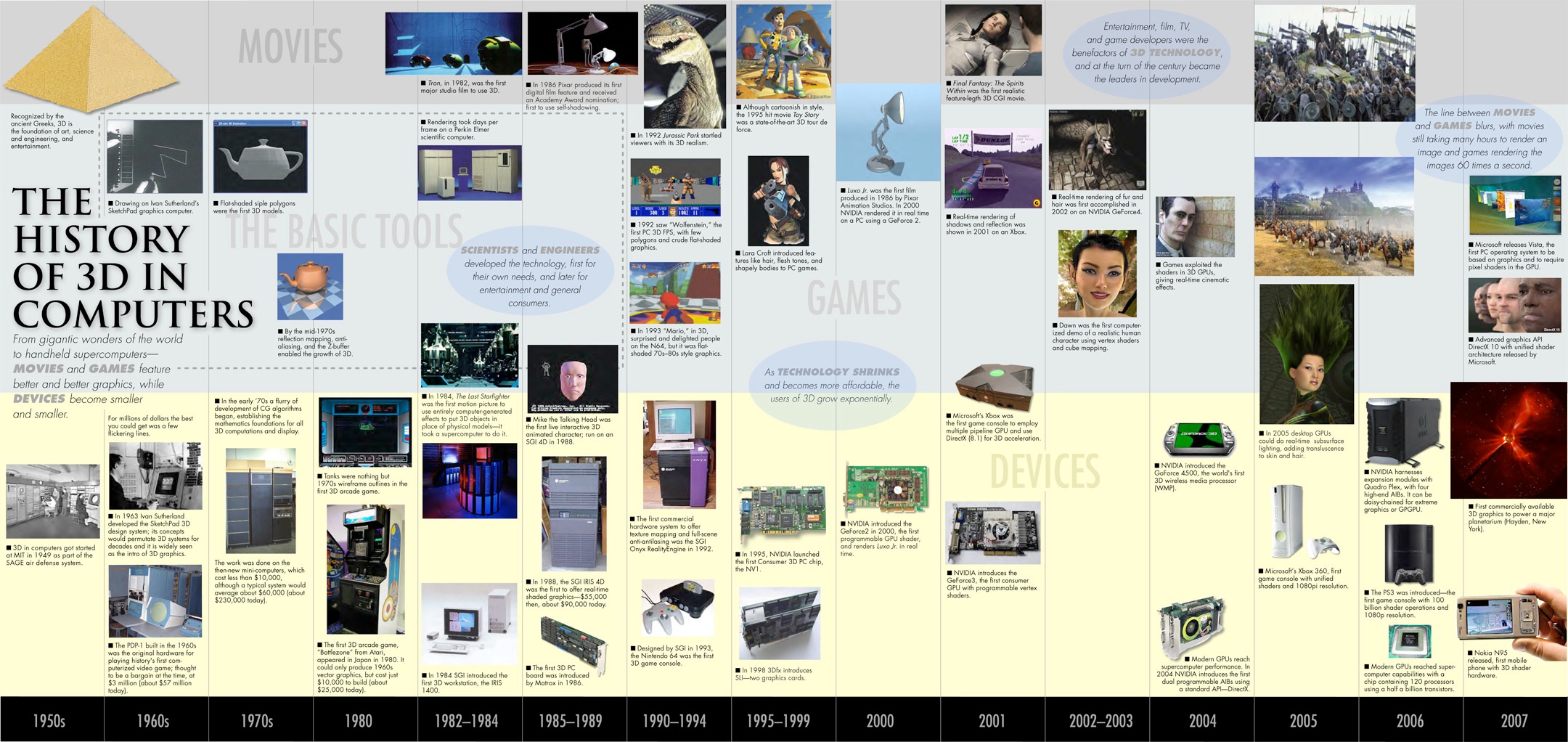

Chapter 14: CG in the Movies

14.2 CGI and Effects in Films and Music Videos

The following writeup, titled The History of Computer Graphics and Effects, was written by Matt Leonard of Digital Dreams & Visions in 1999. He included it on his website, which is inactive.

From the very early days of man’s creation it seems he has been fascinated by the world around him. Early cave paintings show the very first artistic expression of man’s desire to represent this world, showing not only the very form of creation but the living qualities of movement as well. This art form has been developed and diversified over the centuries until the establishment of the motion picture industry in the late 1800s. The first ever special effect or Illusion, as they were known then, was produced in 1895 by Alfred Clark in The Execution of Mary Queen of Scots.

1900s and 1910s

Around the turn of the century, the French magician George Méliès released his first film Indian Rubber Head (1901) bringing his own form of magic to the big screen. The following year he released A Trip to the Moon (1902) and The Dancing Midget (1902), using almost every type of special effects trick still used today.

Effects continued to become more elaborate throughout the next twenty years, through people such as Robert W. Paul and Edwin S. Porter. The technique of using mattes to composite several images onto one negative was employed in such films as The Great Train Robbery (1903) and The Motorist (1906).

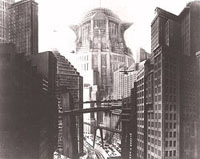

1920s

By the mid 1920s things began to change. Willis O’Brian’s stop motion hit theaters in 1925 in the form of The Lost World, while a year later Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1926) took the effects industry by storm. The Schüfftan Process artfully employed in Metropolis and other movies, utilized forced perspective techniques to create an illusion of size and distance. Such techniques are still common today, being used in such films as Mighty Joe Young and Armageddon (1998).

Alongside this, MGM developed the Composite Reduction process, allowing previously photographed footage to be inserted into specific areas of another frame, as in The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923), The Ten Commandments (1923) and Ben-Hur (1926).

1930s and 1940s

The effects industry continued to grow through the 1930s with such films as King Kong (1933) and Gone with the Wind (1939). In 1934 Walt Disney’s Snow White arrived, ushering in a new era of full-length animated films.

1950s

The post-war years of the 1950s moved the focus of film to outer space, and with the development of the Motion Control Rig by Paramount, more sophisticated shots were developed. Meanwhile the SAGE Machine (Semi-Automatic Ground Environment) was created to follow enemy fighter planes during the Cold War. This provided the first interactive computer graphics. Some of the outstanding effects films of the 50s included Destination Moon (1950), War of the Worlds (1953) and Forbidden Planet (1956). The Blue Screen technique was also invented, enabling a person or object to be filmed against a blue, green, or sometimes red background, and then extracted and composited against a different background.

1960s

There was little technical development during the early 1960s. Ray Harryhausen’s Jason and the Argonauts (1963) came out, which included the famous Stop-Motion skeleton battle sequence which is still inspiring filmmakers today (e.g. The Mummy (1999)). 1963 saw the first Academy Award given for Best Visual Effects, won by Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds. Then in 1968 Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (Oscar winner), began to push the boundaries of special effects once again.

Although the FX industry had not moved forward tremendously until the late 60s, the computer graphics industry had made headway. Ivan Sutherland had invented the Sketchpad interactive graphics software in 1962 and the University of Utah had opened the first CG department in 1966. 2D morphing techniques were first developed in 1967 at the University of Toronto, along with the development of Environmental Reflection Mapping (1976) and Bump Mapping (1978) by James Blinn. Triple-I created the first feature Film appearance of 3D CG, while in 1968 Ivan Sutherland and David Evans joined forces to open the worlds first CG company, Evans & Sutherland, still going strong today. 1968 also saw the arrival of Ray Tracing developed by Bell Labs and Cornell University.

1970s

During the 1970s technology within computer graphics continued to grow, pushed forward by pioneers such as James Blinn and David Em. Bezier curves (1970) were invented along with both Gouraud (1971) and Phong shading (1975). 1975 saw the development of a CG teapot that has now become the computer graphics icon. Ed Catmull went on to develop texture mapping in 1974, refined later in 1976 by James Blinn. Bill Gates founded Microsoft while Steve Woznick and Steve Jobs built the first Apple Computer. Also Quantel created Paintbox, the first graphics product aimed specifically at the broadcast industry.

George Lucas formed Industrial Light and Magic (ILM) to cover the huge array of special effects for his new film Star Wars (1977) (Oscar winner). Among those who joined were Dennis Muren, John Dykstra and Richard Edlund. A host of films began to appear utilizing CG, including The Black Hole (Oscar nominated) and Alien (1979) (Oscar winner). Also in that year Ed Catmull left NYIT and joined ILM to head up their CG department.

1980s

In the 1980s, Triple-I continued their work, producing seven minutes of CG for Looker (1980), while ILM produced the first all-digital CG image for Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982).

Disney’s TRON (1982) was the first extensive use of 3D CG.

Where the Wild Things Are (1982-83) was a pioneering 35mm film test, which digitally composited 3D CG backgrounds with traditionally animated (digitally inked and painted) characters. The work was led by Chris Wedge (now vice-president of Blue Sky/VIFX, (Joe’s Apartment, Star Trek: Insurrection and Bunny). John Lasseter (director of Toy Story, A Bugs Life and Monsters Inc.) left Disney and joined Lucasfilm Computer Graphics Division, working on the CG Endor moon sequence for “Return of the Jedi” (1983) (Oscar winner).

SGI (Silicon Graphics Inc.) was founded by Jim Clark in 1982 and by 1984 they had released their first product, the IRIS 1000. The early 80s also saw a surge in the opening of graphics software houses and the release of new products onto the market. These included 1983: Alias Research Inc. (Alias/1), 1984: Wavefront (PreView), 1985: Softimage (Creative Environment) and 1982: Autodesk (AutoCAD).

Between 1980 and 1985 the special effects and computer graphics industries began not only to settle down but also to merge slightly. Richard Edlund left ILM in 1983 and formed Boss Film Corp., powering onto the market with effects work for Ghost Busters (Oscar nominated) and 2010 (1984) (Oscar nominated). Lucasfilm Computer Graphics Division released The Adventures of Andre and Wally B, directed by John Lasseter. Disney’s The Black Cauldron (1985) became the first animated feature film to contain a 3D element. Lucasfilm Computer Graphics Division produced the 3D animation required to bring to life a knight made of stained glass for the film Young Sherlock Holmes (1985) (Oscar nominated). The project was also the first to composite CG with a live-action background. Dennis Muren was the Visual Effects Supervisor.

In 1986 Pixar was formed when the Lucasfilm Computer Graphics Division was purchased from George Lucas by Steven Jobs for $10 million. The pioneers included John Lasseter, Ed Catmull and Ralph Guggenheim. The company went on to produce the famous Renderman software and animated features including Luxo Jr. (1986) (Oscar nominated), Reds Dream (1987), Tin Toy (1988) (Oscar winner), Knick Knack (1989), Toy Story (1995) (Oscar winner), A Bug’s Life (1998), Toy Story II (1999), For The Birds (2000). (More about Pixar can be found in Chapter 11.)

Howard the Duck (1986) was the first film to use digital wire removal and the first work carried out by the new ILM computer graphics department. Later that year they also worked on Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home (1986) which contained the first use of 3D scanning by Cyberware on a film. During the following year Arcca Animation produced Captain Power and the Soldiers of the Future (1987). It was the first TV series to include characters modeled in 3D entirely within the computer.

By the end of the 80s things were beginning to steam ahead. ILM won another Academy Award for Who Framed Roger Rabbit, and completed the first digital morph for Willow (1988) (Oscar nominated). The following year ILM produced the Donovans destruction sequence for the end of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989). The shot involved scanning multiple film elements into the computer, digitally compositing them together and then scanning back out to film. Also in that year, ILM produced the water pseudopod creature for “The Abyss” (1989) (Oscar winner). The software used included Alias/2 and Photoshop. Dennis Muren, Mark A.Z. Dippe and John Knoll were some of the brains behind the success of the project.

1990s

As we move through the final decade towards the next millennium, the Computer Graphics and Special Effects Industries continue to break new boundaries and bring us the most spectacular array of visual imagery to date.

One of the newer CG companies to appear towards the end of the 80s was Rhythm & Hues. They produced over 30 shots of photorealistic airplanes, bombs and smoke all in daylight for a film Flight of the Intruder (1990). Another new company, deGraf/Wahrman, produced the first CG simulator ride that same year called The Funtastic World of Hanna-Barbera. They also produced the CG head of the robot villain for Robocop 2 (1990).

Disney produced the first completely digital film in the shape of The Rescuers Down Under (1990) and ILM painted the first digital Matte Painting for the film Die Hard 2: Die Harder (1990). The film also contained extensive Blue Screen Compositing for a sequence in which Bruce Willis is ejected out of a plane’s cockpit. Pixar used their new Photorealistic Render software, Renderman, to produce the famous “Shutterbug” image. Autodesk released 3D Studio v1, their own 3D modeling and animation software.

1991 marked the beginning of the ground breaking years. James Cameron’s Terminator 2: Judgment Day (Oscar winner) brought to life by the artists at ILM began to change the way Hollywood perceived computer graphics. It was the first major digital character to be used in a film since the stained glass knight in Young Sherlock Holmes. Alias/2 and Photoshop were used along with a host of in-house tools designed especially for the project. Dennis Muren, Mark Dippe, Stefen Fangmeier, Tom Williams and Steve Williams were some of the people involved. Another major contribution that year came from Disney’s Beauty and the Beast; the ballroom sequence contained a complete 3D rendered background. Stop Motion was superseded by Go Motion created by Phil Tippet for Dragonslayer (1991).

During 1992 ILM continued to push the boundaries in Death Becomes Her (Oscar winner), creating photorealistic skin. Walt Disney also continued to push their techniques in both Aladdin and their short in-house project Off His Rocker. Also Virtual Reality hit Hollywood in the form of the Lawnmower Man (Angel Studios).

Various things happened the following year, but all were overshadowed by the release of Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park (1993) (Oscar winner). ILM employed a huge range of tools to create CG dinosaurs and various other special effects needed for the film. These included Alias PowerAnimator, Softimage 3D, Matador and Lightwave (for simple animatics). 1993 also saw the rise of Digital Domain formed by James Cameron, Stan Winston and Scott Ross.

1994 saw a significant rise in films containing CG. This included Forest Gump (ILM) (Oscar winner), The Flintstones (ILM), The Mask (ILM) (Oscar nominated), The Lion King (Disney), Timecop (VIFX), The Shadow (R/Greenberg Associates) and True Lies (Digital Domain) (Oscar nominated). Also Mainframe Entertainments Reboot came out as the first 100% CG television show. Microsoft bought Softimage, and the computer game Doom was released.

During 1995 SGI acquired both Alias and Wavefront combining the two companies into Alias/Wavefront. In the film industry, Toy Story (Pixar) became the first full-length 3D animated film. Judge Dredd (Kleiser-Walzack Construction Company) became one of the first films to incorporate CG stunt doubles along with Batman Forever (Warner Bros.). ILM released Jumanji, further developing their ability to produce photorealistic hair, and Casper, the first CG characters to take a leading role. Rhythm and Hues Babe won an Academy award for its special effects. Steven Spielberg, Jeffrey Katzenberg and David Geffen joined together to form Dreamworks SKG, and the Sony Playstation was released, and Apollo 13 was released.

By 1996 Dragonheart (Oscar nominated) was finished. Rob Coleman of ILM oversaw hundreds of shots of the talking dragon, Draco, achieving not only a full range of emotional expressions but also the ability to talk. The breakthrough Caricature software or Cari for short, had been developed by Cary Philips and has now become one of ILMs main in-house tools. ILM also relied heavily on Alias/Wavefronts Dynamation particle system software for the movie Twister (Oscar nominated).

Disney’s remake of The Hunchback of Notre Dame used CG to produce crowds, props and other effects. Among the other big films to contain computer animation were Space Jam (Warner Bros.) combining traditional animation with live action, and Independence Day (Oscar winner). The computer game Doom was superseded by Quake, and Autodesk released 3D Studio MAX.

Alias/Wavefronts Dynamation particle system was again used in 1997 by ILM in the creation of a CG cape for Spawn together with realistic goo, drool and saliva. George Lucas restored Episodes 4, 5 and 6 of the Star Wars saga; over 350 shots were modified or added to the existing footage. James Cameron’s company Digital Domain created a huge number of shots for Titanic (Oscar winner) which included extensive use of Motion Capture.

Other CG movies in 1997 were Dante’s Peak, Starship Troopers, The Lost World: Jurassic Park, and The Fifth Element.

Pixar won an Academy Award (in March 1999) for Geri’s Game (1998) which utilized Subdivision surfaces. Radiosity Rendering was used in the creation of Bunny (1998) (Blue Sky/VIFX) which also won an Academy Award the same year. 1998 seemed to be a year of animation involving animals with A Bugs Life (Pixar) and Antz (PDI). Chris Landreth received a Genie Award for his contribution to Bingo, the test project used on the newly released Maya character animation and special effects package from Alias/Wavefront.

1999 was an excellent year for both computer animation and special effects. In May George Lucas released the long awaited Star Wars Episode 1: The Phantom Menace, containing almost 2,000 digital effects created by Industrial Light & Magic under the supervision of Dennis Muren, John Knoll, Scott Squires and Rob Coleman. This was without question the biggest computer animation and special effects film thus far in history. Among the digital tools used to create this ground breaking achievement were PowerAnimator, Maya, Softimage 3D, Commotion, FormZ, Electric Image, Photoshop, After Effects, Mojo, Matador, and RenderMan. Various proprietary in-house software packages were also used including Caricature, Isculpt, ViewPaint, Irender, Ishade, CompTime and Fred.

Among ILM’s other contributions this year are The Mummy, The Haunting and Wild Wild West. Other major effects movies this year include The Matrix, whose special effects were created by Manex Visual Effects, Toy Story 2 (Pixar), Supernova (Digital Domain), Deep Blue Sea (Hammerhead) and Lake Placid (Digital Domain).

As we move into the next millennium, one of the big questions which is often asked within the computer animation and effects community is “what is the next big thing?” Jar Jar Binks from Star Wars Episode 1: The Phantom Menace (ILM) (1999) was the first photorealistic all digital main character in a feature film. People are still fascinated by the concept of entirely digital photorealistic humans. With the improvement in both hardware and software our ability to create more and better digital characters improves by the year.

Some people argue that various questions need to be asked before a huge amount of effort is put into one relatively small area of the industry. Elvis was Elvis not because of how he looked but because of how he moved and acted. There are hundreds of Elvis impersonators in the world, some of which are very good, but none of them are good enough to fool us into thinking Elvis has returned. The closer we get to creating a completely digital character the more our senses seem to alert us to the fact that something is not completely right and therefore we dismiss it as a cheap trick or imitation.

There are no doubt many reasons for using digital humans, such as for stunt stand-ins or simply for those impossible situations conjured up by Hollywood, but as Dennis Muren of ILM once said, “Why bother! Why not focus on what doesn’t exist as opposed to recreating something that is readily available.” Over the last few years we have begun to see animation and special effects creating more impossible situations such as the Flow-Mo and Bullet Time effects shots of The Matrix (1999) and the beautiful artistic style of What Dreams May Come (1998).

Hollywood has found there to be a huge shortage of dinosaurs, dragons, Gungans and various other creatures and characters needed for lead roles in todays motion pictures. A lot of people are very keen to see the progression of digital creatures taken to its logical conclusion of human beings, while others say the focus should be on more artistic effects. Whatever your opinion is, you can be sure of one thing: the magic of computer animation and special effects will continue to advance even faster into the next millennium as a tool to bring to life the dreams of storytellers.

- Poster attributed to Jon Peddie Research (http://jonpeddie.com)

Music Videos

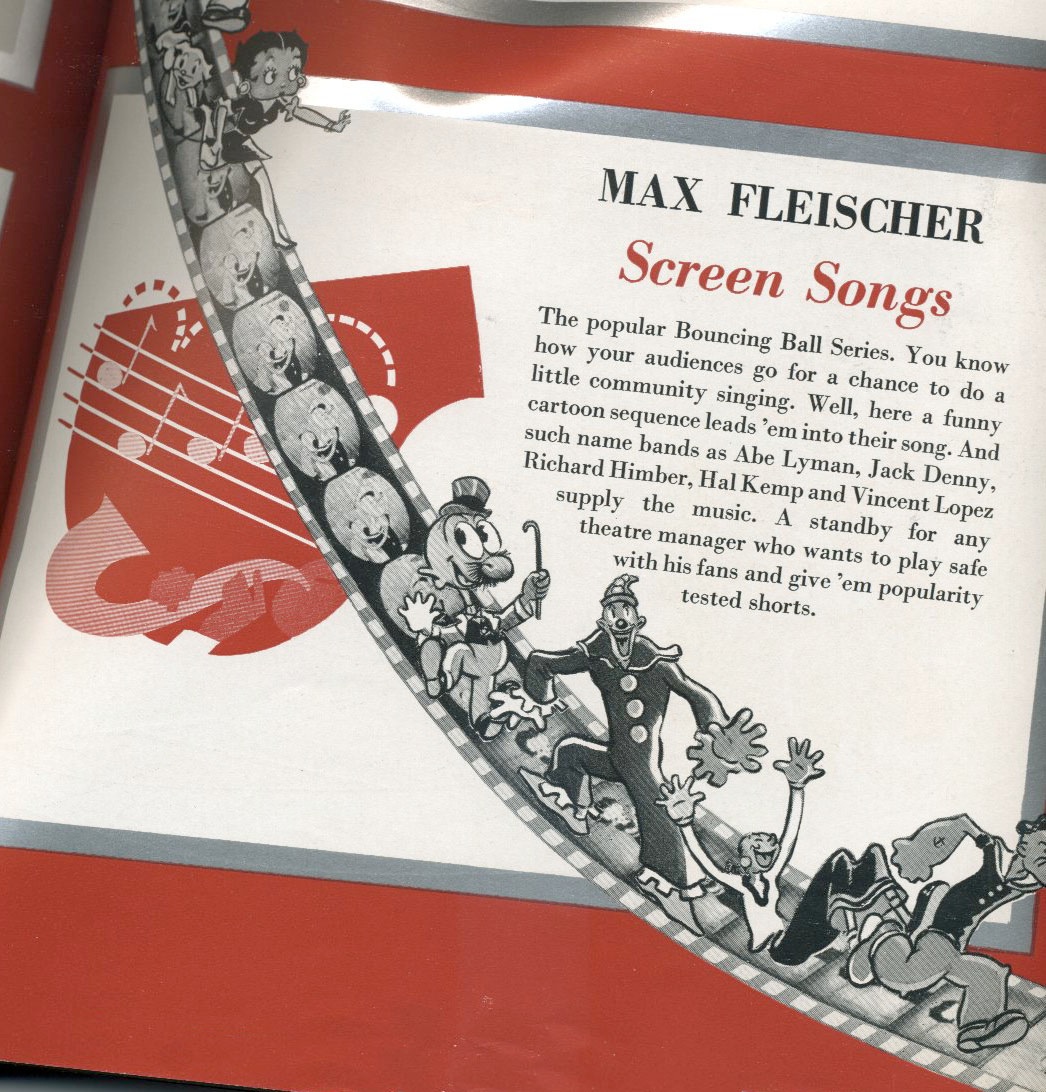

Another film-making effort (closely aligned with movies) that utilizes CG special effects is the creation of music videos. The intent of music videos has always been to promote a song or album, or as an artistic expression of a band or artist. They date back to the early commercial music era of the late 1920s and early 1930s. For example, Max Fleischer’s patented Screen Songs, much like “Sing Along with Mitch” of the early 1960s, were produced as sing alongs for the audience, using the bouncing ball as a way to keep the viewer connected to the music.

Early 1930s cartoons, such as the Disney Silly Symphonies or Fantasia, featured musicians performing in live action or recorded shorts in conjunction with the cartoons. Warner Brothers often featured short musical numbers to promote their upcoming films.

Movie 14.2 Disney Silly Symphony Farmyard Symphony (1938)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NoFWBCBk0YY

Rock groups of the 1960s and 1970s used the genre to promote their music, often filming at live concerts or lip-syncing in different environments. Some people point to the Beatles Hard Days Night as the real launching pad for music videos, but many acknowledge that it was Queen’s Bohemian Rhapsody that really was the video that convinced the industry of the potential for this art form.

Movie 14.3 Queen – Bohemian Rhapsody – 1975

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=irp8CNj9qBI

Michael Nesmith of the Monkees developed a TV show to feature music videos, called PopClips, in the late 1970s. It was tested on Warner’s QUBE cable network in Columbus, Ohio. Nesmith later produced an award winning compilation called Elephant Parts, and a show that aired in 1985 called Television Parts. But the music video industry really didn’t take off in a big way until 1981 with the first broadcast of MTV.

Most of the music video productions during this early time used video effects, such as green screen, slit scan or other motion effects, as the special effects component of the pieces. Although there were some early music videos that used basic CG effects, the first real documented production was done by Alex Weil, Jeff Klein and Charles Levi of Charlex in 1983 for the video for the Cars song You Might Think.

Movie 14.4 You Might Think

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3dOx510kyOs

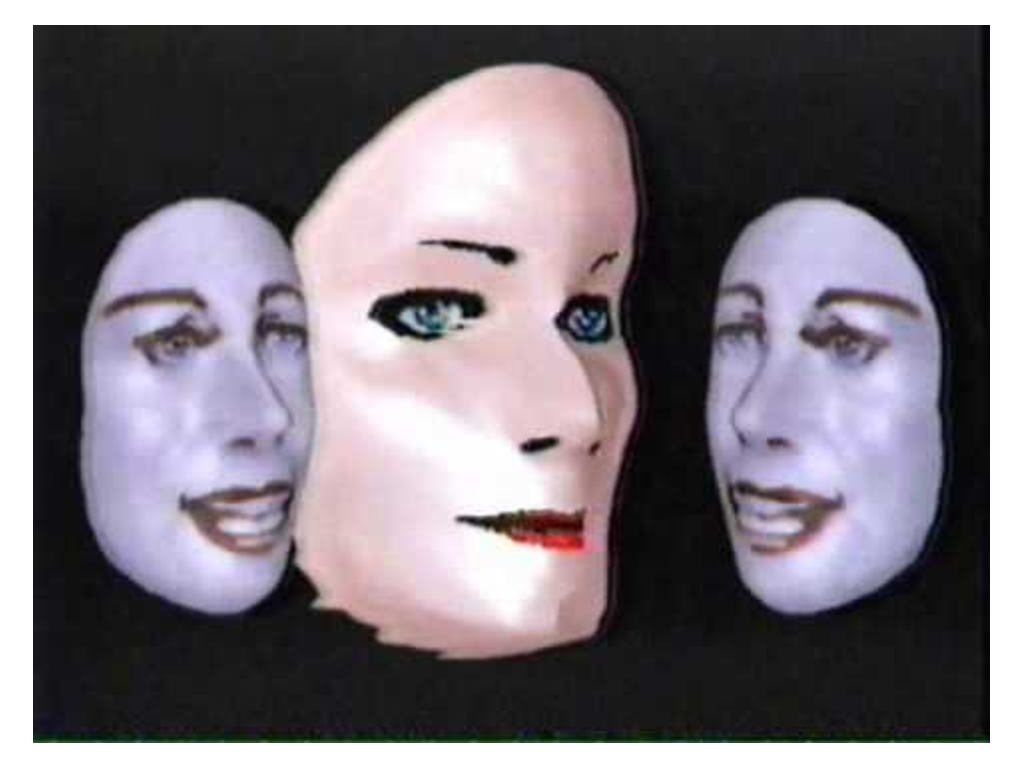

That same year Rebecca Allen at New York Institute of Technology produced talking faces (à la Fred Parke) for the Will Powers song Adventures in Success and CG bodies for Smile. (Will Powers was actually the stage name used by celebrity photographer Lynn Goldsmith when she created a self-help comedy music album entitled Dancing for Mental Health).

Movie 14.5 Adventures in Success

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j5BLHeOdvYI

Movie 14.6 Smile

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g43lzoRamWE

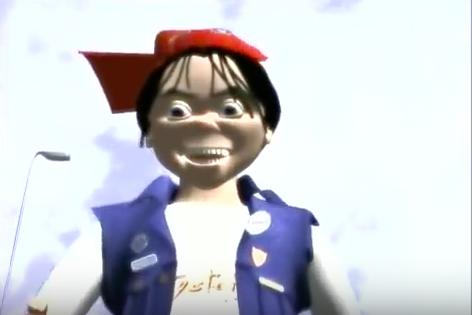

The next music video that featured CG generated characters was the video for Dire Straits’ Money For Nothing in 1985. It has often been designated as the first music video that featured computer graphics, but that is obviously incorrect, although it was very instrumental in shaping the acceptance of the technology for use in the creation of this art-form. It was produced by Gavin Blair and Ian Pearson at Rushes Post Production using the Bosch FGS-4000 animation system and Quantel. Blair and Pearson later produced the popular ReBoot computer-animated series at their new company Mainframe Entertainment.

Movie 14.7 Money for Nothing

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lAD6Obi7Cag

Also in 1985, Digital Productions produced the graphics for Hard Woman from Mick Jagger’s She’s the Boss album (although the song on the video was not the same recording from the album, as it was re-recorded by Jagger and the Hooters for this made-for-MTV video.) The video can be seen via the link in Section 4 of Chapter 6.

Many think that the 1986 video for Peter Gabriel’s song Sledgehammer was CGI, but it in fact was produced by Aardman Animation using stop motion and claymation, much like the other Aardman production Wallace and Gromit. Gabriel did use computer generated animation extensively in his video for Steam in 1992.

Movie 14.8 Steam

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qt87bLX7m_o

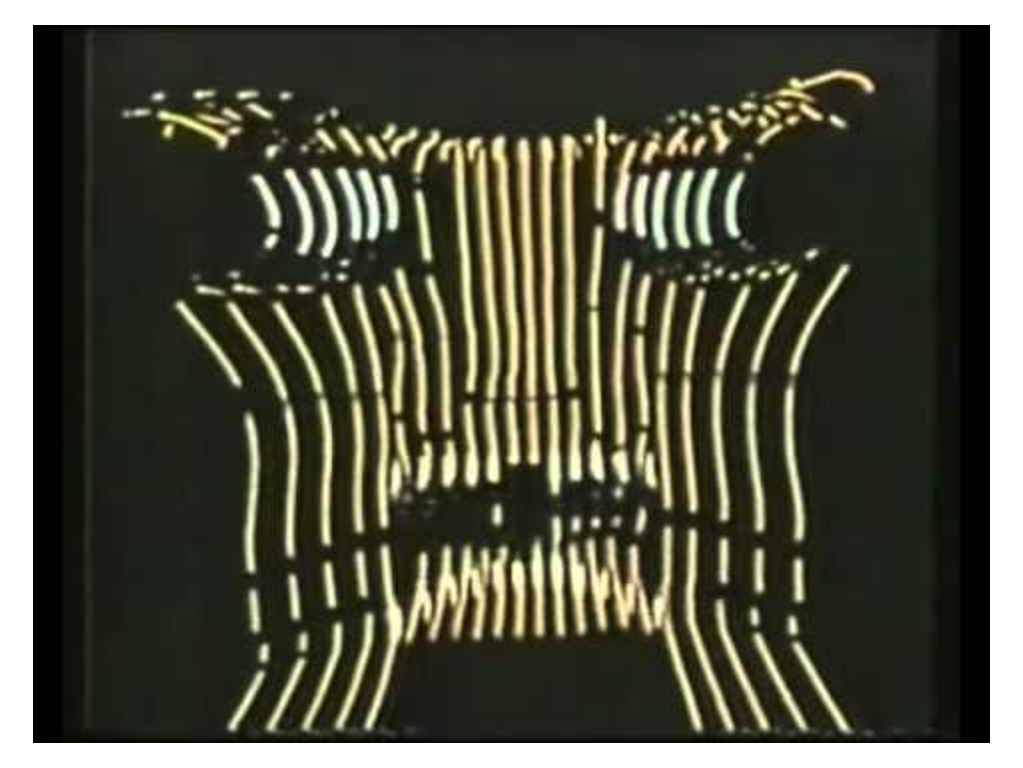

In 1983 Rebecca Allen at NYIT also produced wireframe graphics in the widely acclaimed video for Kraftwerk’s Musique Non Stop from the album Electric Cafe. Allen used the digitized faces of the band to generate the images on the proprietary NYIT animation system, but the animation wasn’t used immediately. It sat for three years until the album was completed and Allen reworked the imagery. The video has enjoyed frequent airing on MTV and highlight shows, and also has been regarded as a true artistic statement, having been featured in exhibitions as well.

Movie 14.9 Musique Non Stop

In 1991 Pacific Data Images produced a portion of the video for Michael Jackson’s Black or White, using their successful morphing technique to cleanly transition from one face to another. The concept had previously been used in videos for The Reels (Shout and Deliver)[1] in 1981, and Godley and Creme (Cry) in 1985, although the technique used in these two videos was actually analog video dissolves.

Movie 14.10 Black or White (excerpt)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R4kLKv5gtxc

Movie 14.11 Cry

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BALmXecO0DE

Also in 1991 Todd Rundgren used the Amiga and the Newtek Video Toaster to produce graphics for the video for Change Myself. Rundgren produced the graphics in part to show the capabilities of the Toaster.

Movie 14.12 Change Myself

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7mH8PaWbi1E

Rundgren talks about how he made the video in a speech at a LA SIGGRAPH 91 meeting at

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jhs24mL8Lx0

Rundgren was active in early music video days, and his video for the song Time Heals was one of the first on MTV. He produced a piece for RCA, accompanied by Gustav Holst’s The Planets, that was used as a demo for their videodisc players.

In the 1990s, Rundgren was a big proponent of the capabilities of the Toaster, and he made several videos with it after Change Myself. He also used the system for videos for Fascist Christ and Property from his album No World Order. Later, he set up a company to produce 3D animation using the Toaster, and produced the company’s first demo, Theology.

Another influential production from Ian Pearson was the 1992 video for Def Leppard for their anthem Let’s Get Rocked from their album Adrenalize. Pearson produced CG effects for a stage in the shape of the British flag, as well as a CG character named Flynn.

Movie 14.13 Def Leppard – Let’s Get Rocked

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BO1Nae_EBvQ

The German band Rammstein used a combination of CGI and stop-motion to portray an army of ants, mobilized underground by the hero in the video, attacking some foraging beetles in their song Links 2-3-4 (Left 2-3-4). The video was created in 2001. The video clip referenced here is the “how it was made” video, and is in German with English subtitles.

Movie 14.14 Links 2-3-4

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ph-CA_tu5KA

The video for Creed’s song Bullets is interesting because of its use of video game technology to create the imagery. It was created in 2002 by the team at Vision Scape Interactive. The band was digitized and the imagery created by the game developers included accurate representations of each member, down to their their tattoos. An article from MTV.com described the goals:

“It was important that Mark [Tremonti] do battle with an axe because he’s a guitar player,” added Matt McDonald. “And then Scott Phillips is a drummer, so we gave him two swords. And the designs on the swords came from his tattoos. It was really important to the guys that we matched all their tattoos perfectly. The only thing we did different is we made them a little buffer than they are now.”

Movie 14.15 Bullets – excerpt

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oPzhUp8mWgs

There have been many more music videos that utilize computer graphics for the visual effects since these early contributions, including videos for Bjork, Coldplay, Shania Twain, Radiohead, Michael Jackson, Gorillaz and others. Wayne Lytle’s Animusic effort, founded in 1995, is an example of a company fully devoted to videos that accompany music. In the case of Animusic, the videos are “compilations of computer-generated animations, based on MIDI events processed to simultaneously drive the music and on-screen action, leading to and corresponding to every sound.”

The skeleton from Robbie Williams Rock D.J. video is particularly noteworthy. The 2000 video showed Williams dancing in a roller rink, trying in vain to get the attention of the D.J. He takes extra steps, stripping off his clothes, then his skin, and finally his muscles so that what remains is a dancing skeleton, controlled with motion capture data. The video was banned in several countries because of the shock value, but won the MTV award for effects that year.

Movie 14.16 Rock D.J.

http://www.dailymotion.com/video/x2rmj_robbie-williams-rock-dj-uncensored_music

A list of the MTV Video Music Award for Best Special Effects can be found here.

Todd Rundgren had previously released a software paint package for the Apple II, called the Utopia Graphics System, and with David Levine, the screensaver Flowfazer – Music for the Eyes.

- Keyboardist Karen Ansel of the Reels left the band and became an animator at ILM, where she worked on the effects for the movie What Dreams May Come and other well known movies. ↵