Chapter 17: Virtual Environments

17.2 Virtual Projection

Around the same time, Thomas A. Furness, a scientist at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio, began to work on better cockpit technology for pilots. “I was trying to solve problems of how humans interact with very complex machines,” said Furness. “In this case, I was concerned with fighter-airplane cockpits.” Aircraft were becoming so complicated that the amount of information a fighter pilot had to assimilate from the cockpit’s instruments and command communications had become overwhelming. The solution was a cockpit that fed 3-D sensory information directly to the pilot, who could then fly by nodding and pointing his way through a simulated landscape below. Today, such technology is critical for air wars that are waged mainly at night, since virtual reality replaces what a pilot can’t see with his eyes.

“To design a virtual cockpit, we created a very wide field of vision,” said Furness, who now directs the University of Washington’s Human Interface Technology (HIT) Lab. “About 120 degrees of view on the horizontal as opposed to 60 degrees.” In September of 1981, Furness and his team turned on the virtual-cockpit projector for the first time. “I felt like Alexander Graham Bell, demonstrating the telephone,” recalled Furness. “We had no idea of the full effect of a wide-angle view display. Until then, we had been on the outside, looking at a picture. Suddenly, it was as if someone reached out and pulled us inside.”

The Human Interface Technology Laboratory is a research and development lab in virtual interface technology. HITL was established in 1989 by the Washington Technology Center (WTC) to transform virtual environment concepts and early research into practical, market-driven products and processes. HITL research strengths include interface hardware, virtual environments software, and human factors.

While multi-million dollar military systems have used head-mounted displays in the years since Sutherland’s work, the notion of a personal virtual environment system as a general purpose user-computer interface was generally neglected for almost twenty years. Beginning in 1984, Michael McGreevy created the first of NASA’s virtual environment workstations (also known as personal simulators and Virtual Reality systems) for use in human-computer interface research. With contractors Jim Humphries, Saim Eriskin and Joe Deardon, he designed and built the Virtual Visual Environment Display system (VIVED, pronounced “vivid”), the first low-cost, wide field-of-view, stereo, head-tracked, head-mounted display. Clones of this design, and extensions of it, are still predominant in the VR market.

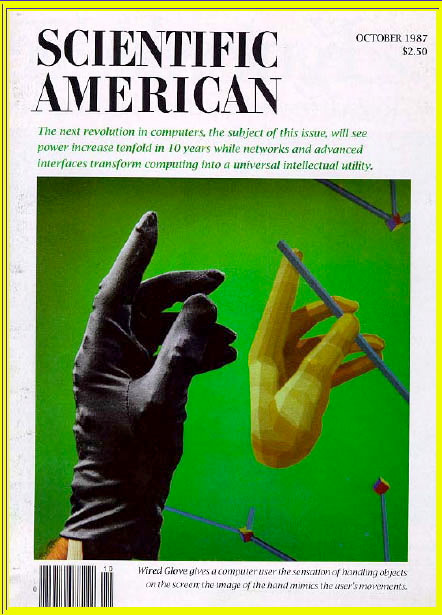

Next, McGreevy configured the workstation hardware: a Digital Equipment Corporation PDP-11/40 computer, an Evans and Sutherland Picture System 2 with two 19″ monitors, a Polhemus head and hand tracker, video cameras, custom video circuitry, and the VIVED system. With Amy Wu, McGreevy wrote the software for NASA’s first virtual environment workstation. The first demonstrations of this Virtual Reality system at NASA were conducted by McGreevy in early 1985 for local researchers and managers, as well as visitors from universities, industry, and the military. Since that time, over two dozen technical contributors at NASA Ames have worked to develop Virtual Reality for applications including planetary terrain exploration, computational fluid dynamics, and space station telerobotics. In October 1987 Scientific American featured VIVED – a minimal system, but one which demonstrated that a cheap immersive system was possible.