Chapter 4: Basic and applied research moves the industry

4.5 The Ohio State University

Charles Csuri, an artist at The Ohio State University, started experimenting with the application of computer graphics to art in 1963. (See Art, Computers and Mathematics, by Charles Csuri and James Shaffer, AFIPS Conference Proceedings, V33, FJCC, 1968). His efforts resulted in a prominent CG research laboratory that received funding from the National Science Foundation and other government and private agencies. The work at OSU revolved around animation languages, complex modeling environments, user-centric interfaces, human and creature motion descriptions, and other areas of interest to the discipline.

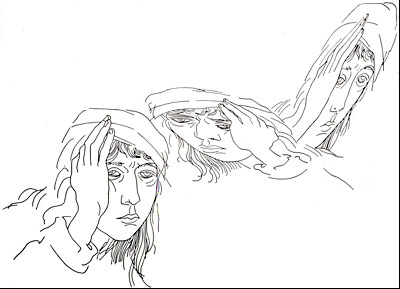

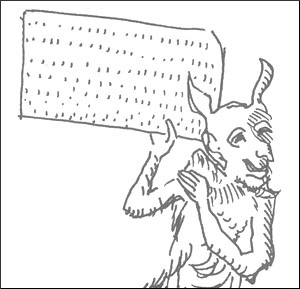

Working as a painter, Csuri[1] became increasingly fascinated with the computer and its potential as an artistic tool. His early “computer” work involved the creation of an analogue device to process images, much like a pantograph traces an image. By changing the length of one or more components, the image could be redrawn in a transformed state. In a pointed commentary on the state of the technology at the time he created an image of a devil holding a punch input data card.

In 1967, he used a line drawing of a man, and working with a fellow faculty member (James Shaffer) from the Department of Mathematics, modified its shape using a sine curve mapping and a mainframe computer (IBM 360). Lacking an output medium for recording this primitive animation, he plotted the intermediate frames on paper using an IBM plotter to create a haunting blend of images (called Sine Curve Man).

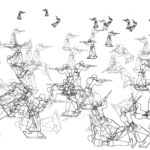

That same year, he continued with this experimentation on other drawings, including one of a hummingbird in flight. Csuri produced over 14,000 frames, which exploded the bird, scattered it about, and reconstructed it. These frames were output to 16mm film, and the resulting film Hummingbird was purchased by the Museum of Modern Art in 1968 for its permanent collection as representative of one of the first computer animated artworks.

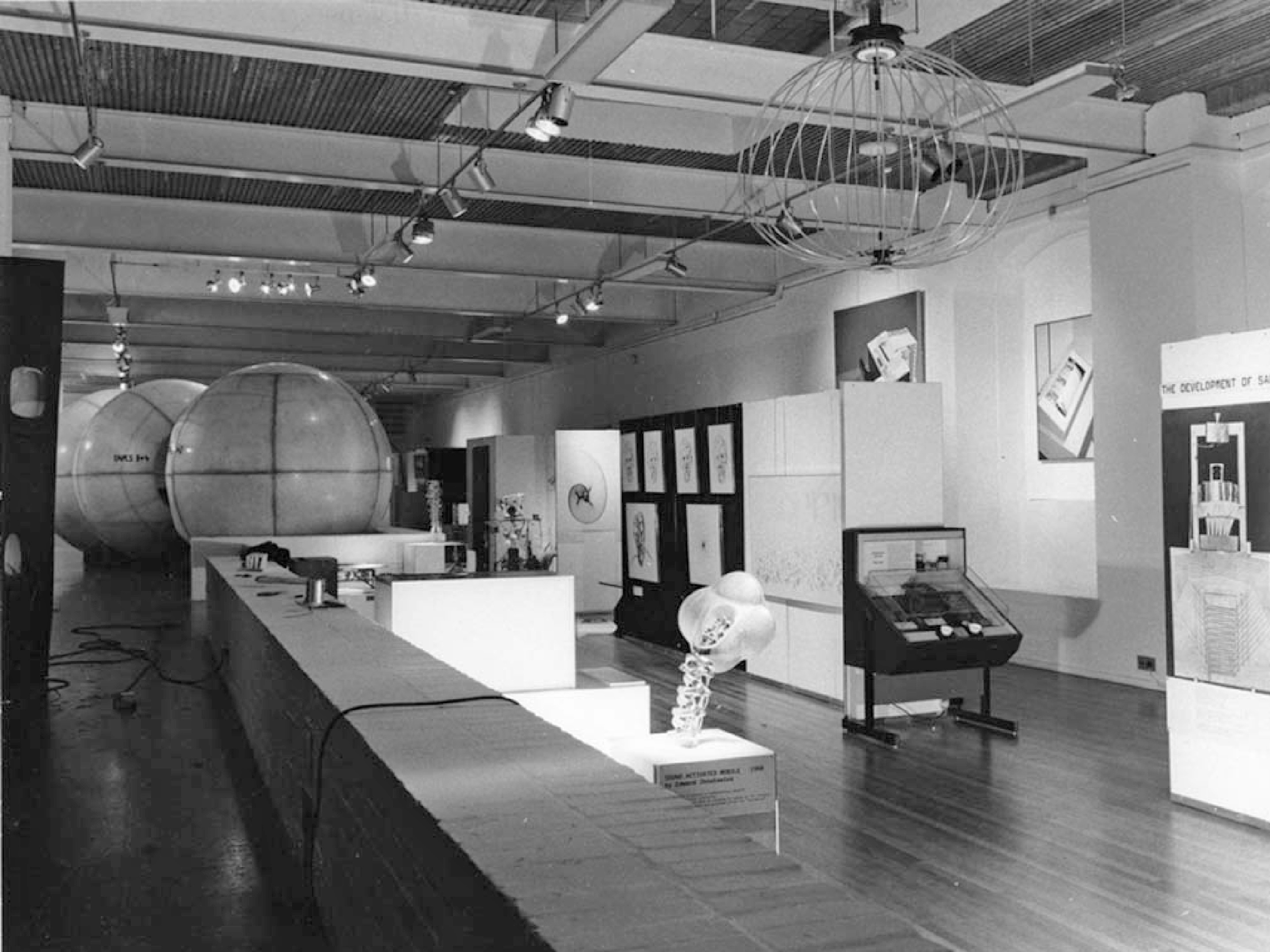

Also in 1968, Csuri was one of the featured artists at an exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, and his work in computer animation was featured in the catalogue titled “Cybernetic Serendipity – the computer and the arts,” published that year by Studio International. This publication was the one of the first collections that dealt with “…the relationships between technology and creativity.”

At the end of the decade, Csuri was also experimenting with many different kinds of output media, collaborating with mathematicians and scientists. One of his partners created a “tool” for defining a mathematical surface (what became known as the Fergusen patch) that Csuri then had sculpted in wood on an Engineering Department milling machine.

Csuri continued to work with graduate students and fellow faculty members from the arts and sciences for the next several years, experimenting with different approaches to instructing the computer to display and animate the various artifacts that he conceived. In 1969 he received a prestigious grant from the National Science Foundation to study the role of the computer and software for research and education in the visual arts. This was very unusual, for an artist to receive an NSF grant, and showed the level of significance of the work at OSU at the time. (In fact, an internal report done at the National Science Foundation stated that the greatest impact on the field of computer animation could in part be attributed to the work at the Computer Graphics Research Group at Ohio State.)[2]. Additional images from Csuri can be seen below in Gallery 4.1.

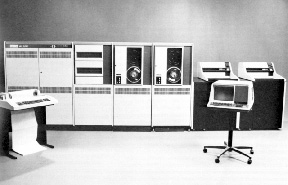

In 1971 he proposed a formal organization, called the Computer Graphics Research Group (CGRG) in order to realize the potential of the application of computer animation to the studies by students in the Art Department, and to have a formal cohort that could attract external research support. Members of CGRG included faculty and graduate students from Art, Industrial Design, Photography and Cinema, Computer and Information Science, and Mathematics. Grant proposals were submitted to agencies and programs both in and out of the University, and funding was provided for studies that would extend the capabilities of the evolving discipline. The group was housed in space in the OSU Research Center at 1314 Kinnear Road on the OSU campus. Equipment in the lab at this time included a 32K IBM 1130 computer interfaced to an IBM 2250 Model IV graphics display, and the FORTRAN programming language was used as the primary programming environment.

Research and development work conducted by CGRG members during this early period included hidden line and visible surface algorithms, linear interpolation, path following, data smoothing, shading and light source and reflection control, compound transformations, 2D and 3D data generation and sophisticated interaction techniques. This seminal work evolved into a general interest in dynamic systems and languages for applications in computer-controlled display and motion. In 1970, Csuri published one of the first papers related to the complex issue of animating objects in real time.

Csuri was awarded his second NSF grant in 1971 for a project titled “Software and Hardware Requirements for Real Time Film Animation.” The University provided matching equipment support, and the CGRG installed a 48K word PDP-11/45 computer and a Vector General graphics display with 3D hardware transformation capabilities in 1972. This grant supported Computer Science graduate students Tom DeFanti, who developed the animation language Graphics Symbiosis System (GRASS) in 1972, and Manfred Knemeyer, who developed the ANIMA system in 1973 for defining computer generated motion, using an integrated programming language. (Staff member Gerard Moersdorf helped write a large amount of the GRASS code.) Both of these systems were designed with traits that DeFanti, who went to the EVL at the University of Illinois, called habitability (ease of use by novices) and extensibility (the use of stored files to be interpreted by the system), and both linked to external controls like dials, buttons and joysticks in addition to command line control.

Expanding on Csuri’s early work in blending of line drawing images, Mark Gillenson developed a system (WhatsIsFace) that used techniques of key frame animation to blend images to create facial drawings, a system that created a significant amount of interest in the police and investigative communities. This system was one of the first formal contributions to the technology that is now called “morphing“.

CGRG efforts embraced a fundamental philosophy that these complex computer animation capabilities could be made available on microcomputers (eg, PDP 11/45) and could be easy to use. The group continued to receive NSF and other internal and external support for this effort, and published extensively during the early 1970s on animation and animation control as well as human-computer interfaces. The University expanded their support and funded additional equipment (another Vector General display, a computer-controlled camera system, and a communications link with the University’s PDP-10 mainframe.) In 1975, Csuri contracted with John Staudhammer of NC State (through his company Digitech) to build a special “run-length encoding” storage and display device that allowed CGRG to move from a strictly vector display environment to raster and color graphics.

Richard Parent joined CGRG in 1974 to develop geometric modeling tools for animation (his 1977 dissertation received the “Best PhD Dissertation Award” from the National Computer Conference). During this early period, Alan Myers studied and developed rendering algorithms (coded in the PDP 11 assembly language) that could run efficiently in the minicomputer environment to make high quality imagery.

Ron Hackathorn worked to expand Knemeyer’s Anima animation system, and Tim Van Hook brought a user perspective to the design, as well as a knowledge of real time issues.

Movie 4.13 Pong Man

Pong Man was created by Tim VanHook to demonstrate the use of Anima II to produce creature motion.

The development activities resulted in the ANIMA II animation system, which supported procedural modeling and run-length encoding algorithms, the DG modeling system for data generation, and other supporting systems and languages. The group expanded to include Rodger Wilson and Wayne Carlson, and a number of other graduate students from various departments during this period.

Early investigations into “creature” animation were both influenced by and supported the work of OSU Prof. Robert McGee and his 8-legged articulated mobile robot designed and built at Ohio State.

CGRG team members used the systems that were developed in the lab to generate computer animations that were shown throughout the mid to late 1970s, and published the results of their work in SIGGRAPH proceedings and other journals. The group was also featured in many popular media presentations, including television features such as PM Magazine and the national CBS Sunday Morning with Charles Osgood.

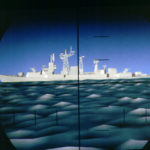

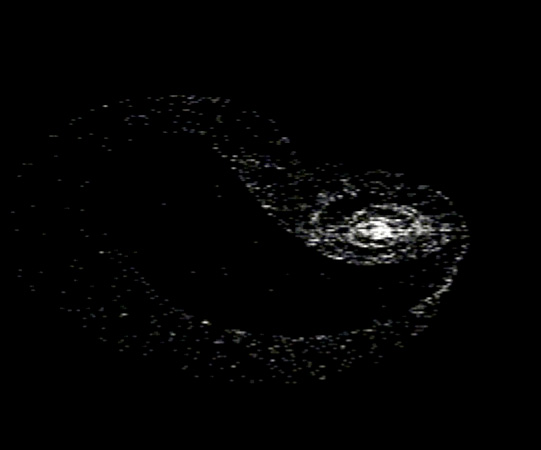

Important work produced during this period included a visualization of interacting galaxies, which was shown on the Carl Sagan Cosmos series, by Bob Reynolds (it was updated with a complex particle system in 1978 by Wayne Carlson), studies of time in virtual environments, the use of CGI in visualizing statistical data, the use of animated sequences to help teach language constructs to deaf children, terrain modeling and harbor pilot training simulation, and computer art. CGRG created one of the first 3D computer generated animations used for a television station, the CBS affiliate WBNS-TV in Columbus, Ohio in 1978.

Funding for the research at CGRG was provided by the University, the National Science Foundation, the Naval Weapons Training Center, the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, and the U.S. Department of Education. Carlson and Rick Parent were also part of a consulting team to Boeing to conduct a major graphical user interface study for the Air Force ICAM (Integrated Computer Aided Manufacturing) program.

In the late 1970s, the focus of the work turned in the direction of increased complexity of modeling and animation and visual accuracy. Ron Hackathorn and Rick Parent developed the next generation animation system, called ANTSS, which was one of the first systems that combined motion specification and rendering in the same system. As mentioned earlier, Parent received his PhD degree in 1977, which focused on a modeling system called DG, which was likened to a tool for sculpting clay in the computer environment. Parent was appointed the Associate Director of the lab after his graduation.

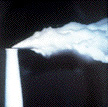

Wayne Carlson worked with Rodger Wilson and Bob Marshall to expand the procedural animation capabilities introduced by Martin Newell of the University of Utah, and also developed an expanded surface modeling environment that used higher order curves and surfaces, such as Bezier and b-splines, as part of his PhD research. Carlson also investigated points as a display primitive that could be used to efficiently compute and display “fuzzy” objects, i.e. those with no “solid” 3-D structure (eg, smoke, fire, water, etc.) He applied this research to generate an image of a smokestack, and he recalculated the interacting galaxies sequences first produced by Reynolds, increasing the geometry from several hundred geometric primitives (stars) to over 30,000 in each galaxy.

Carlson’s DG2 system expanded the modeling work of Rick Parent, and was a system for modeling geometry that included points as a geometric primitive (what would later become known as particle systems), boolean operators on surface patches, and a unified approach to sweep operators. CGRG images from this period can be seen in Gallery 4.2 below.

Frank Crow, a PhD student of Ivan Sutherland at Utah,was recruited from the University of Texas and worked with approaches to increased scene description and rendering capabilities and continued his work with shadows and antialiasing that were started at the University of Utah. At CGRG he investigated multi-processing approaches to image synthesis and other algorithmic solutions for complex images. He later went to Xerox PARC, Apple Computer, Interval Research, and then to NVIDIA.

During Crow’s tenure at OSU, the PDP-11/45 was replaced with one of the earliest VAX 11/780 models on the market, and the FORTRAN and assembly language code was translated to the C language in the Unix environment.

Dave Zeltzer developed goal-directed motion description capabilities for skeletal and creature animation (the Skeletal Animation System – SAS). His system and the underlying theories are some of the most significant contributions to the area of autonomous legged motion description in the discipline.

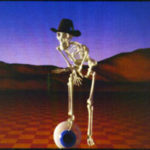

Don Stredney (the Ohio Supercomputer Center) pushed the limits of the modeling systems of Carlson and Parent to develop complex anatomical models, including the skeleton”George” used by Zeltzer in his research. George became a graphics “cult” figure, and the geometric model was distributed widely throughout the field.

Mark Howard moved from Staudhammer’s NC State program and designed and built a controllable 512×512 frame buffer that allowed real-time playback of animation tests. This frame buffer and later versions of the design were the mainstay of the image creation and representation capabilities at CGRG and later at Cranston/Csuri Productions.

Julian Gomez developed TWIXT, a track-based keyframe animation system. This system allowed for the specification of key-framed motion for independent objects that moved over the same time interval. It had real time playback, with shape morphing, and was device independent.

Other important work done during this period included films Snoot and Muttly by Susan Van Baerle and Doug Kingsbury, Trash by John Donkin, Tuber’s Two-Step by Academy award winner Chris Wedge, Vision Obious by Ruedy Leeman, early character animation by Michael Girard and George Karl, and animations by Susan Amkraut, Marsha McDevitt, Thuy Tran, Kevin Reagh, Anne Seidman, Tom Hutchinson, Bill Sadler and others. CGRG images from this period can be seen in Gallery 4.3 below.

CGRG continued to advance, concurrently with the efforts at Cranston/Csuri Productions (see Chapter 6) across the lobby in the 1501 Neil Avenue building. In 1987 Tom Linehan and Chuck Csuri oversaw the conversion of the Computer Graphics Research Group into The Advanced Computing Center for the Arts and Design, with funding from a long-term Ohio Board of Regents Academic Challenge grant. ACCAD was established to provide computer animation resources in teaching, research and production for all departments in the College of the Arts at Ohio State.

Movie 4.14 Dawn of an Epoch

Video of CGRG and ACCAD’s role in the advancement of computer graphics and animation as it becomes a widely used scientific tool.

During this period, significant research and production was done in the area of animation by many faculty, staff and students, including Joan Staveley, James Hahn (rigid dynamics), David Haumann (flexible dynamics), Chris Wedge, Brian Guenter (parallel graphics), Doug Roble (compositing), Paul MacDougal (levels of detail), Scott Whitman (Parallel algorithms), Beth Hofer (facial animation), Susan Amkraut and Michael Girard (flocking and human locomotion), Midori Kitagawa (Boolean operations), John Chadwick (layered skeleton control of human motion), David Ebert (procedural animation), Jim Kent (3D object morphing), Rob Rosenblum (rendering and animation of hair), and Ferdie Scheepers (animation and modeling of human musculature). The building housing ACCAD (and C/CP) can be seen in the Movie 4.14 as well as in Gallery 4.4 below.

There were also many arts and design students who were involved in award-winning computer animations, and who are now very important educators or animators for the industry. A list of the alumni of the program and their affiliations can be found at the ACCAD web site at

http://accad.osu.edu/people/alumni

ACCAD was established as an interdisciplinary research center, and was instrumental in many research investigations around computer graphics, animation, visualization, multimedia, etc. A partial listing of the projects and funding can be found on the research section of their website at

https://accad.osu.edu/research-gallery

Wayne Carlson became the Director of ACCAD in 1991 after Csuri retired. In 2000, Maria Palazzi returned to Ohio State as Associate Director, and in 2001 assumed the Directorship when Carlson became the Chair of the Department of Design at OSU.

In 1985 Rick Parent started the CG Lab in the Department of Computer Science in the College of Engineering at OSU. He was later joined by Wayne Carlson, Roni Yagel, Ed Tripp, Kikuo Fujimura, Roger Crafis, and others. Early focus of the lab was on computer animation, particularly character motion, procedural effects, visualization, and geometric modeling. Parent wrote the definitive textbook on computer animation, Computer Animation, Algorithms and Techniques, and graduate David Ebert edited the book Texturing and Modeling.

Several influential graduate students came through the CG Lab, some working specifically in the lab, and others also working through ACCAD. For example, Doug Roble won an Academy Award for his work at Digital Domain on motion tracking software; Michael Girard started his own company in 1993, Unreal Pictures, that created the animation software Character Studio, later purchased by Discreet; Dave Haumann was the lead technical director on the 1997 Academy Award winning Geri’s Game; Steve May became the Chief Technology Officer for Pixar.

Graduates of the CS program work in many corners of the computer graphics industry, as technical directors in most major production companies, in the game industry, at NVIDIA, Adobe, Sony and other companies, as well as teaching in some of the top universities in the country. More information can be found at the CG Lab web site.

Chris Yessios started on the faculty at Ohio State after receiving his graduate degree in 1973 from Charles Eastman’s Computational Design Lab at Carnegie-Mellon University, where he became interested in the applications of CAD to architecture. He and his students in the School of Architecture started looking at how this evolving field could be used to impact the way CG and CAD could be used in the design process. At the time, the university was using 2D drafting and 3D modeling programs running on mainframes. Frustrations with the cost of these large computers and some of the emerging turnkey CAD workstations changed when the early Macs became available. They started developing software that would run on the personal computer and provide sophisticated 3D capabilities.

In 1990, Yessios and a former student David Kropp, founded AutoDesSys (standing for Automated Design Systems), and developed the popular 3D modeling software, form•Z. They also developed the software products RenderZone and Bonzai3D. The AutoDesSys software was designed to be used in architecture, product design, interior design and illustration applications.

Movie 4.15 Form•Z 2007 User Reel

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3PewiPQdA5g

Some Early CGRG and ACCAD videos

Movie 4.16 Hummingbird (1966)

Movie 4.17 Rigid Body Dynamics (Hahn 1989)

Movie 4.18 PM Magazine

Movie 4.19 Interacting Galaxies (Reynolds 1977)

Movie 4.20 Anima II

Movie 4.21 The Circus

Movie 4.22 Procedural Terrain Models

Movie 4.23 Snoot and Muttly (Van Baerle / Kingsbury 1984)

Movie 4.24 Broken Heart (Staveley – 1988)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iPLFB6_xpAI

Movie 4.25 Tuber’s Two Step (Wedge – 1985)

Movie 4.26 Zeltzer SAS V1 SAS V2

Movie 4.27 Girard/Karl Creature Motion Studies (1985)

Movie 4.28 Eurythmy (Girard and Amkraut – 1989)

Movie 4.29 Coredump (1989)

Movie 4.30 Tectonic Evolution (1995)

Art, Computers and Mathematics, by Charles Csuri and James Shaffer, AFIPS Conference Proceedings, V33, FJCC, 1968

Csuri, Charles. Computer Animation. Proceedings of SIGGRAPH 75.

Csuri, Charles. Real Time Film Animation, 9th Annual UAIDE Proceedings, 1970.

Rick Parent, A System for Sculpting 3D Data, Proceedings of SIGGRAPH 77.

Ron Hackathorn, Anima II – A 3D Animation System, Proceedings of SIGGRAPH 77.

Wayne Carlson, Robert Marshall, and Rodger Wilson. “Procedure Models for Generating Three Dimensional Terrain,” Computer Graphics, V14, #2, July, 1980, pp. 154-161.

Wayne Carlson. “An Algorithm and Data Structure for 3D Object Synthesis Using Surface Patch Intersections“, Computer Graphics, V16, #3, July, 1982, pp 255-263.

C. Csuri, R. Hackathorn, R. Parent, W. Carlson, M. Howard. “Towards an Interactive High Visual Complexity Animation System,” Computer Graphics, V13, #2, August, 1979, pp. 289-299.

Ohio State Pioneers Computer Animation:Making Birds Fly and Babies Walk. Computer Graphics World article about CGRG by Tom Linehan, October 1985

Csuri, Charles. Art and Animation, IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications, January 1991

Gallery 4.1 Other Csuri Artwork

- Chuck Csuri at CGRG (1978)

- Scene from Hummingbird

- After Mondrian

- Shaded Man

- Random War

Gallery 4.2 Early CGRG Imagery

- Fall Tree, made with Procedural Modeling

- Summer Tree

- Forest of Trees

- Particle System Smoke Cloud

- Patch Intersection Algorihtm

Gallery 4.3 Other CGRG Imagery

- Data made with DG2

- Scene from a movie by Frank Crow showing capabilities of the scn_assmblr animation control system.

- Scene from Snoot and Muttly by Kingsbury and Van Baerle

- “George in the Desert” – data created by Don Stredney on DG2

- Image from paper by Jim Kent – 3D interpolation

- Scene from Norfolk ship pilot simulator.

- Scene composite from Zeltzer SAS system

Gallery 4.4 CGRG/ACCAD Imagery

- Scenes from “Butterflies in the Rain”

- Stills from muscle simulation – Ferdie Scheepers and Steve May

- Cranston Building, home of CCP and CGRG

- CCP lobby

- Csuri was featured in a 1995 cover article of the Smithsonian magazine, written by Paul Trachtman and titled "Charles Csuri is an 'Old Master' in a New Medium". ↵

- Csuri was featured in a series of prestigious retrospective exhibitions of his work. The SIGGRAPH professional graphics organization hosted an exhibition of his work titled "Beyond Boundaries, 1963-present" in 2006 in Boston. This exhibition also traveled to the Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts in Taiwan in 2008, to several venues in Europe, and to the Urban Arts Space in Columbus, Ohio in 2010. ↵